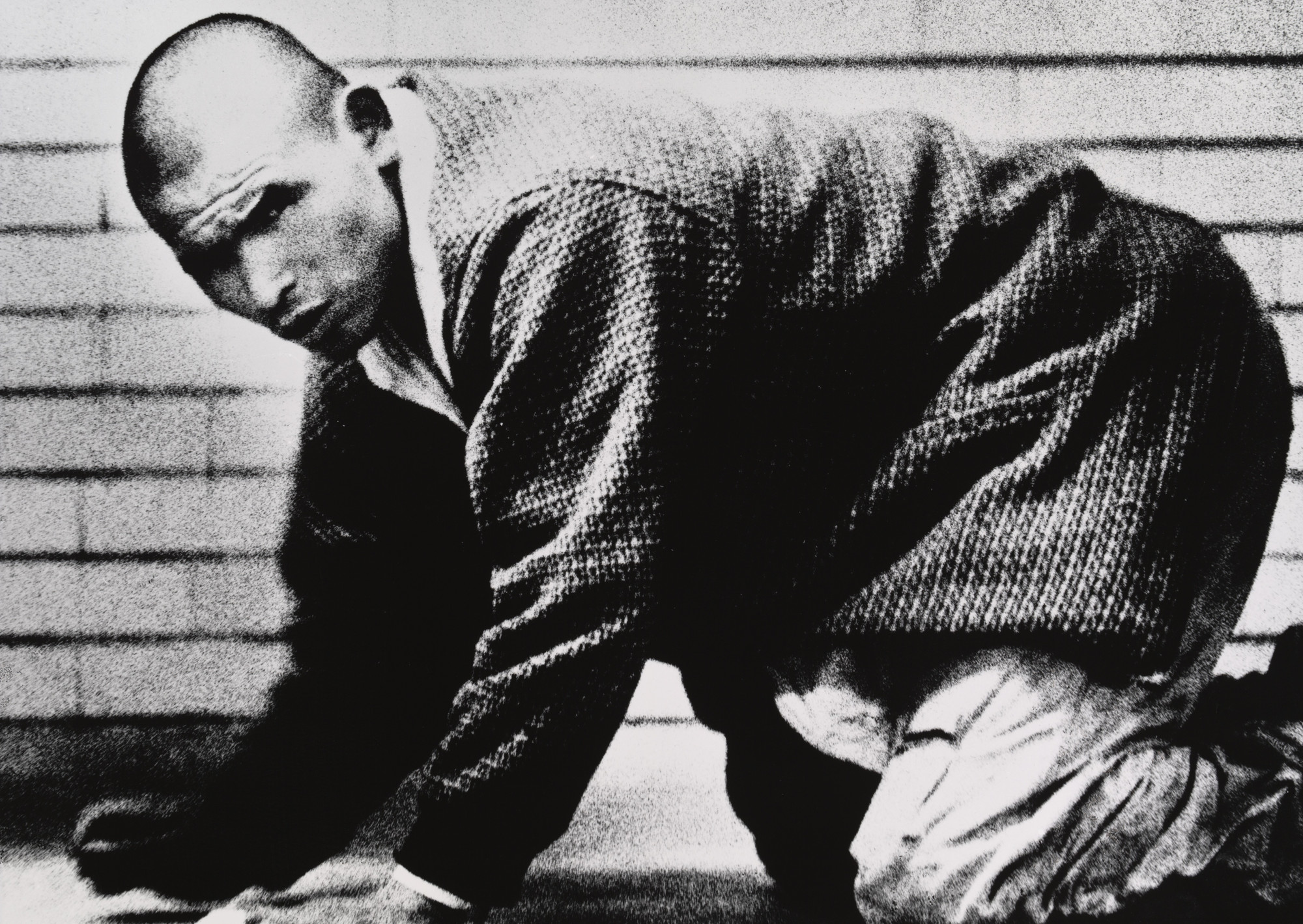

Stray Dog, Misawa, Aomori (1971)

Moriyama is conspicuous for the brutality with which he distorts photographic description: his pictures are sooty with grain, blotchy with glare, often out of focus or blurred by movement, often defaced by scratches in their negatives.

By Leo Rubinfien, October, 1999

The photographer Daido Moriyama, whose first U.S. retrospective is now on view in New York, has spent the last 35 years elaborating a somber, alienated vision of postwar Japan. Moriyama is the author of over 20 books of photographs–notably Nippon Theatre (1968), Hunter (1972), Farewell to Photography (1972) and Light and Shadow (1982)(1). His current retrospective, “Daido Moriyama: Stray Dog,” was organized by Sandra Phillips, curator of photography at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, in collaboration with Alexandra Munroe, director of the Japan Society Gallery in New York.

While the writers, filmmakers and architects of contemporary Japan have long enjoyed great respect in the West, its painters and photographers have not. Moriyama’s is the first full retrospective given to any Japanese photographer by an American museum of the first rank. The show reminds us that not all of the finest modern art has been the product of Europe, Russia or the Americas. The accompanying catalogue should be obtained for any library concerned with contemporary photography or Asian modernism.

“Vintage” prints have generally been thought less important in Japan than in the West. Although none of Moriyama’s work is more than four decades old, many prints that he made in his early years have been lost or destroyed. Nevertheless, thanks to a remarkable effort by Phillips, the present show consists largely of early prints, which are unlikely to be brought together again soon. These images have a tentativeness that is often absent from Moriyama’s later prints, and that gently offsets the fierce subject matter of his pictures.

.jpg)

Moriyama’s best work everywhere implies a trauma that must have occurred just outside the limit of our vision, just before we got to the scene, or just beyond the reach of our memory.

Since the Second World War, the image of the stray dog has wandered into Japan’s best art often enough to have us ask what, in that famously rule-bound, rank-conscious land, such a pariah might mean. As nearly as I can tell, its earliest appearance was in Akira Kurosawa’s 1949 film Stray Dog, where it was not a character but the metaphorical name for a young, murderous pickpocket, demobilized from the Emperor’s army into the bomb-blasted city with no home to return to. At the start of the chase, the stern senior detective warns that such mined men am stray dogs, to be put down before they turn into mad dogs, but his despondent acolyte pleads for compassion, recalling that in the chaos of 1945 he might easily have become such a dog himself. The stray is there again in Susumu Hani’s exquisite She and He (1960), this time as the companion of a pathetic ragpicker who is one of the two principals of the story. The dog is pretty much this outcast’s alter ego, and when at the film’s denouement it is hideously tortured by the children of a cell-block town of materialistic salary-men, the man suffers equally, and we with him.

The pariah appears still again, begrimed, toothy, at once feral and cringing, in Daido Moriyama’s extraordinary photograph Stray Dog, Misawa, Aomori (1971), and if this image has won Moriyama many admirers, its subject seems to have affected the artist himself no less: Moriyama identified with it in the titles of three books, Dog’s Memory (1984), Dog’s Time (1995), Dog’s Memory–the Last Chapter (1998),(2) and again not long ago, when speaking of how he photographs. “When I go out into the city I have no plan,” he said. “I walk down one street, and when I am drawn to turn the corner into another, I do. Really I am like a dog: I decide where to go by the smell of things, and when I am tired, I stop.”(3)

There are beautiful Samoyeds and Huskies in Japan, and one notices especially the expensive lapdogs Of genteel ladies, Pomeranians and Pekingese groomed every day, as soft as powder puffs. The mongrels Americans cherish–“he’s part Doberman, part Shepherd,” an American will say with pride–are rarer. Japan is as ethnically closed a country as any on earth, and half-breed animals are not much better loved there than half-breed people. If he is asked about mutts and strays, the walker of Japan’s cities will recall rat-faced scavengers in the back alleys of the night-towns, their greasy, colorless hair repulsive, their expression always frightened–and frightening.

For Moriyama to identify himself with these beasts is remarkable. The West maintains a pantheon of alienated heroes, and in its romantic modernist tradition, the bohemian, rebel, tramp or hollow-hearted etranger have been thought bearers of authenticity and moral legitimacy. But in Japan an outsider is truly an outsider. The hero-outcasts of its premodern folklore, the dispossessed lord Yoshitsune, for example, or the 47 vengeful ronin, are not so much opponents of society as plaintiffs for a justice that society has refused but could easily give. The true renegade–with no home village, no pedigree, no uncles or cousins to protect him, no company, guild, obligations, diploma or calling card–is suspicious even to the most free-thinking Japanese. In the less liberal he provokes revulsion and anger.

The life of the Japanese outsider himself, then, is necessarily filled with bitterness, self-hatred and despair. These emotions are sometimes openly expressed in art–for example at the end of Stray Dog, when the killer has finally been wrestled into the mud and daisies in a ditch on the edge of Tokyo and, inarticulate with pain, begins to writhe and cry in hysterical, falsetto shrieks. We understand intuitively that he is railing at a power to which he was never equal, and whether we consider it the power of society or of karma, he is utterly helpless before it, lost, damned. His is the pure, terrible grief-noise of the defeated man, the “scream against the sky,”(4) as Yoko Ono named it. If Moriyama’s photographs had a sound, it would be this sound.

The sense of defeat in Moriyama’s work was recognized early by the artist Tadanori Yokoo, whose essay “A Cowering Eye,” tells us that the pictures in the photographer’s most powerful book, Hunter, were made from “the point of view of a peeping Tom, a rapist … a criminal.”(5) Indeed, cowering is present in the book’s original title, the first of whose two ideograms means “ambush” and conveys a nuance that the English “hunter” loses: a kariudo is really an ambusher, no bold chasseur at all but a man who must hide in a blind. It always seems to me that the photograph of the stray dog in Misawa presents that moment when, uncertain whether to lunge or flee, two exhausted gutter animals reckon which one is better able to make food of the other. The extraordinary thing, of course, is that this picture puts the viewer, the human being, no higher than the ghastly dog. It tells me how far I may fall, how far I have fallen, when I cannot know if I will devour or be devoured.

Moriyama’s pictures therefore include many that neither describe Americanization nor express any longing for old, vanished Japan.

Here is a little more of what Moriyama offers: a proper housewife who appraises the artist from behind a chained-up door in a grim apartment block, distrust and contempt plain in her eyes; a wincing singer at the microphone, his mouth a gash full of mined teeth; a beggar with the shaven skull of the gulag, crawling in a Shinjuku tunnel; a dirty-footed sailors’ whore in a white minidress, tiptoeing through the garbage in a midnight alley;, a taxicab exploding in flames; a movie-star poster in which Brigitte Bardot opens her thighs lasciviously on the seat of a huge motorcycle; endless shelves and crates of Coke, Campbell’s Soup and Green Giant “Cream Style” Golden Corn; an idiot boy, his eyes rolling to heaven; a horsefly on a hotel window;, a woman squatting to urinate on a boulevard; Osaka, so strangled by smoke and yet so gloriously lit by the setting sun that it is at once a place of epiphany and a city in hell.

Moriyama is conspicuous for the brutality with which he distorts photographic description: his pictures are sooty with grain, blotchy with glare, often out of focus or blurred by movement, often defaced by scratches in their negatives. Because Moriyama is often looking through some barrier–steamy glass, a grille, a hole in a door–one may begin to squint a little before realizing that the picture will never get any clearer. None of this represents bad technique. It is wholly purposeful, and gives the photographer an expressive leverage perfectly adjusted to his subjects: if the actor impersonating a geisha was already grotesque before Moriyama arrived, the distortions that the photographer adds in evoke the shock of discovering him. Many of Moriyama’s pictures thus hit us doubly–with a frightening or repellent thing, and with a manner of rendering it that is the visual equivalent of nausea, vertigo or horror.

In Route 16, Yokota (1969), for example, which fills one endlessly mysterious page of Hunter, the image of two children is so degraded by haste, grain and the fence through which Moriyama is looking that no one will ever really know what they were up to. A Japanese boy grabs here for a Western girl who is running on a patch of grass, and while we somehow know that he cannot catch her, the moment in which he nearly does so is full of the scent of the evilly erotic, of the ravishment of virgin by virgin, of humiliation, miscegenation. Our grip on the facts is as feeble as the facts themselves are ominous, and the picture leaves us to brood on our inability to understand. Moriyama’s best work everywhere implies a trauma that must have occurred just outside the limit of our vision, just before we got to the scene, or just beyond the reach of our memory. We feel that what we are getting now is its residual radiation.

It is often said that the trauma about which Moriyama’s work seethes, mutters and curses is that primary disaster of Japan’s last 60 years–its defeat in the Second World War, together with the “Americanization” that has questionably been said to follow. Some of the artist’s first strong photographs were, in fact, made in Yokosuka, a principal base of the Imperial Navy until 1945 and of the U.S. 7th Fleet since then, and many of his later pictures also come from base towns–that of the stray dog from Misawa, that of the boy chasing the girl from Yokota. This is a very complicated issue, however. Moriyama began to photograph almost 20 years after the surrender, at a time when Japan was politically independent and more prosperous than it had ever been, yet he takes much from the defeat-obsessed Decadent writers of the late ’40s (he says that the much-beloved novelist Osamu Dazai was, along with Niepce, the photographer Nakaji Yasui and drugs, his main interest in his 41st year). At the same time, he is rarely as direct about Americanization as his early mentor, the superb photographer Shomei Tomatsu, who wrote recently that “the American Occupation of Japan is something from which I cannot avert my eyes.”(6)

Tomatsu presents the Western influx into Japan quite factually, marking fiercely the difference between what is American and what is Japanese, and he laments most of what he sees. He addressed himself early to the A-bombed city of Nagasaki, then searched among the sailors and night butterflies of the bar-towns that abut the U.S. bases in Japan, proceeding from them to the tawdry American junk that was sold to and devoured by the Japanese young, to the boom of the 1960s and finally to the Southwest islands, where he sought an untainted surviving essence of the spirit of Japan. He is an elegist, always full of the feeling of loss.

In Moriyama’s very different world, the foreign is everywhere, but it is hard to distinguish from the native.

In Moriyama’s very different world, the foreign is everywhere, but it is hard to distinguish from the native. His Japan has fully absorbed the American vires into its own chemistry, and while a Japanese might hate this condition, there is no possibility of reversing it. John Szarkowski recognized the divergence of Moriyama from Tomatsu when their work was still quite new, writing that “the suggestion of the nihilistic that exists in Tomatsu’s work has been made boldly and effectively explicit by Moriyama…. [W]hat in the older man is a sense of tragedy becomes in the younger an occult taste for the dark and frightening.”(7)

Moriyama’s pictures therefore include many that neither describe Americanization nor express any longing for old, vanished Japan. On the face of it, what have a stray dog, a rumbling Kyoto streetcar, a naked woman from whose bed the artist has just crawled, a Borsalino hat or a stained washbasin to do with either? While, for Tomatsu, Americanization can be rationally denounced and (at least in one’s imaginings) undone, it is a given for Moriyama and he turns from its obvious manifestations toward material that is ever more idiosyncratic and personal. “My photographs have always been … private letters that I write and send to myself,” he says.(8) At moments, we may detect in him an echo of the Gutai artists of the early ’60s, who urged that art should record the physical motions that an artist’s body makes as he works, and might even include its excrescences. Moriyama is the only photographer I can name who has published an excellent picture of the parings from his own fingernails.

Without knowing him, Moriyama dedicated Hunter to Jack Kerouac, but I think this may mislead Americans. In Moriyama there is neither the exultation with which the novelist tumbled out across Walt Whitman’s continent, nor the serenity–one species of cool–that the Dharma bums pursued across the Pacific. Kerouac is in fact so much a scion of the American victory that it is hard to see what he offered young Japanese of his time, except the picture of a freedom their country had forbidden and that was, for most, still unattainable. Moriyama evokes, instead, the febrile days of the dead-end bohemian–that way of life in which one rolls out of bed in a strange apartment at 11 in the morning, drinks cheap coffee on the sidewalk till 1 and spends the afternoon searching the city for a girl who turns out not to be there, or for a friend who might have money to lend; in which one slides down through the night from bar to club to bar and ends up in the bed of someone who, that morning, one had never heard of at all.

Moriyama’s work shares much here with Kenzaburo Oe’s celebrated novel A Personal Matter (1969), in which Bird, a young man who dreams of exploring Africa but is a helpless prisoner of duty, suddenly finds himself the father of an infant born with its brain outside its skull. Little in modern fiction is more sickening than Bird’s monstrous new baby (one thinks of the cockroach body of Gregor Samsa), and Bird responds to it by plunging into a weeklong debauch, in which he plots with an old girlfriend to murder the child in its crib. The poisoned world of A Personal Matter–the tawdriness of everything, the harshness of all light and sound, the booziness, the always-raw nerves, the estrangement of parents, the pointlessness of the future–is exactly Moriyama’s.

One of the most curious aspects of Moriyama, again, is that he researched anguish so deeply at Japan’s best moment. With the Tokyo Olympics of 1964, Japan finally seemed to itself to have recovered from the war, to have become the home of a peaceful, constructive optimism such as the whole world might wish to learn.(9) It is equally mysterious that Moriyama’s work declines to cite the loss of the graces of old Japan as the reason for its despair. The few pictures he presents of cherry blossoms–the country’s magnificent ancient symbol of youth, glory and early heroic death–render them a sinister, metallic gray. Even if we could reach that kind of beauty, he seems to say, it wouldn’t do us any good. Like Oe, then, Moriyama appears to be islanded in time. Occasionally this condition is comical, as when he writes endearingly of how, at 23 and just arrived in Tokyo, he “strode down the Ginza, radiant in my green tweed and black mambo pants.”(10) Normally, though, hopelessness about the future would seem to be his main preoccupation. One of the cruel beauties of his picture of the stray dog in Misawa is that it collapses the years into a hard, nasty present: the past is useless here, and one’s fine hopes for the future will never exempt one from having to face the dog down. He is an ugly barrier between now and everything one yet wishes for; until you have settled with him, you will go nowhere at all.

To say only that Moriyama has reclaimed and reconceived his country’s old, exquisite voice, with its contorted expressions, would fail, though, to grasp the full, ironic poignancy of his achievement.

What Szarkowski called Moriyama’s nihilism is closer to the spirit of Baudelaire or of Rimbaud than it is to much that is American. It runs so deep in him that, in one of his most interesting turns, he rejected photography itself. In Farewell to Photography (1972), the thick volume he published after Hunter, he pushed the degrading of the image to the limit; almost every picture there is blurred, too dark, too light or otherwise hard to read. We would be mistaken, though, to think that Moriyama was going for any sentimental fogginess, derived perhaps from old Japanese painting. What he reiterates again and again here, I am sure, is fury–about photography’s inability to say all that Moriyama would have it say, about its being unequal to the truth of terrible experience. The book suggests that description can only be a lie, that we can never know the world through seeing it, and in fact Moriyama has made the fascinating reflection that he was always working against photography. One suspects that he could also have said, with Rimbaud, that he practices his art “because it is the least odious occupation.” John Nathan, the translator and filmmaker, points out that the English words “farewell to photography” give an incorrect softness to shashin yo sayonara, whose import is more like “photography, good riddance!”

The darkness in his work has remained unmitigated, and as we begin to understand him precisely, we may recognize the traces of an old emotion, long repressed in Japan and hard for Americans to remember.

We may infer a clue to Moriyama from the ending of A Personal Matter, in which Bird’s malaise abruptly dissipates. He decides not to kill his helpless baby or run for Africa, but to make a modest new life at home as a guide for foreign travelers; he casts his old girlfriend away and goes back, contrite, to the hospital to find that the doctors operated successfully while he was on the bottom. The infant will recover. This astonishing dual reversal of the story tells us that, to Oe, there was no way out of decadence and despair except the path of classical Western humanism, with its proscriptions against cruelty. The word in Bird’s mind at the end of the story is not “hope,” but the un-Confucian and more than a little Christian “forbearance”; and in his Nobel Prize acceptance speech, the writer spoke of “the determination we made in the postwar ruins of our collapsed effort at modernization … to establish the concept of a universal humanity.”(11) Ultimately, Oe rejected the romance of disillusionment and chose the liberal spirit of Olympics Tokyo, in company with most of the Japanese people.

Moriyama found no such exit. The darkness in his work has remained unmitigated, and as we begin to understand him precisely, we may recognize the traces of an old emotion, long repressed in Japan and hard for Americans to remember. The historian John Dower has suggested ingeniously that we can find, in the Decadents’ obsession with defeat and victimhood, a survival of the older feeling of attraction to the war, to the “mesmerizing grandeur of destruction and the ‘strange beauty’ of people submissive to fate,” to “the beauty of falling victim to causes greater than oneself.” Dazai’s much-loved novel The Setting Sun (1947), he writes, revealed “tortured, twisted links between the `old’ and the `new’ Japan.”(12) One opposite, certainly, of the new prosperity that is so sickening in the work of Moriyama and Oe is the purifying austerity that was celebrated, three decades before them, in the Imperial religion of the “national body” and the military code.

These speculations would thus be incomplete if we did not consider one last artist, the strange, disgraced Yukio Mishima, whom literary Japanese of the 1960s, Moriyama among them, admired more than any other author. Today, Mishima is remembered less for his stories than for his bizarre end–possibly the century’s most spectacular case of an artist repudiating art in favor of action–his self-murder by harakiri, the traditional stomach-cutting of the samurai, in the office of the commander of the new Japanese army. He wanted to see the restoration of Imperial power and military culture, he wrote, and he is therefore called a political rightist. The label helps us little toward understanding him, though. The leftist students who fought the police in the streets and tunnels of Shinjuku, and who appear in a few of Tomatsu’s and Moriyama’s photographs, also showed an appreciation for regimental order, uniforms and weaponry–one never seen on the streets of Paris, Chicago or Berkeley in 1968. Their abhorrence of Americanization, for that matter, was hardly remote from the open nationalism of the Japanese fight, and where Japan of the 1960s is concerned, the designations “right” and “left” lose much of their Western meaning. We would do better to think of the idealistic internationalism of some people and the sentimental militarism of others.

The traumas of World War II and Americanization were felt as painfully on one side as on the other. There was, with the country’s surrender, a deliberate excision from the being of Japan of an element that had been central in its culture for a very long time–its ferocious, unpitying militarism. The hauteur of the Emperor’s captains will still frighten us if we watch an old documentary like Fumio Kamei’s Shanghai (1938) and see them strutting among their ragged Chinese subjects; and we will still be impressed by the grandeur of the Imperial battle cruisers shining on the Huangpu River. A kind of emasculation was performed on Japan at the war’s end, just as was done to Kurosawa’s desperado when young Toshiro Mifune, looking for all the world like Gregory Peck, pinned him down in the mud and took away his gun. It was against this surgery on the mind of the nation that Mishima made his amazing gesture or, more precisely, against the absence, the emptiness, which remained where the military self had been.

Moriyama too, I think, addresses himself to this concealed aftereffect of defeat and Americanization, less concerned as he is with their physical manifestations than with the need to invent photographic cognates for their marks on the spirit, to make us experience what Tomatsu tells us about. The blinding picture in Hunter of two boy-soldiers, Coffee Shop, Hamamatsu (1968), is uncharacteristically plain about this: they are blanched, mild men we cannot imagine slaughtering at Nanking, or throatcutting in the ravines of Guadalcanal.

I would never suggest that Moriyama is of Mishima’s school. The writer’s late extravagances seem absurd beside the meticulous intimacies of Moriyama, who, in any case, hung around with a leftish crowd in the balmy, tear-gassed springs of ’69 and ’70, and says now that he never liked politics anyway. (The one time that a friend got him to go to a demonstration, he says, he ducked into the first Almond coffee lounge he saw and sat out the tumult.) Still, it is reasonable to ask if Moriyama was not perhaps contemplating the same dark phenomenon that Mishima was raging at as he descended into madness; it might in fact suggest why the “occult taste for the dark and frightening” should have emerged in Moriyama when it did (and as it also did in his contemporary, the photographer Masahisa Fukase). For 40 years Japan had been driven by the grandiose ambition for empire and then, after its failure, by the urgent project of reconstruction. Now, with prosperity, no simple, noble purpose was at hand. Just as Moriyama shows little nostalgia for old Japan, warlike or otherwise, the liberal’s high-minded ideals would have seemed uselessly abstract, perhaps even naive, to the intuitive photographer.

If Mishima and Oe may be taken to represent the poles of Japanese belief in those years, then the stray dog Moriyama–yet a derashinei (deracine), as Japanese bohemians of the ’60s and ’70s liked to say–wanders waywardly between them. He bears the reality, as those writers’ grand beliefs could not, of a moment when the old map was no good and a new one had not yet been drawn. In holding so insistently to the minutiae of the present, he is as true a humanist as the modern Japanese arts have produced.

In the end, Americanization cannot be measured. Although the presence of things Western in Japan is obvious, one suspects that the Japanese are rather less Americanized than they have often claimed. Insofar as it is an accurate name for anything, “Americanization” may simply be a trope that has been useful to them in telling of their society’s pains and stresses. Japan continues, as it has since at least 1868, to be a place of idiosyncratic culture and insular behavior. And, in fact, its old esthetic of asymmetry and dissonance finds new life in Moriyama’s pictures. Their harshness and distortion, their scarified description and sense of omen, should remind us of the violent figure that the black blot makes on white in classical calligraphic painting; of the stunning sound of wooden clappers against silence, just before the play begins; of the distressed pizzicato of the samisen; of the shriek of the actress at the moment of the hero’s downfall; of the grotesque Noh mask; of the shadowy puppet-handlers of the Bunraku, crouching like assassins. To say only that Moriyama has reclaimed and reconceived his country’s old, exquisite voice, with its contorted expressions, would fail, though, to grasp the full, ironic poignancy of his achievement. This has been to direct that voice to the lingering heart-pain of postwar Japan, and so to give his country’s agonies an uneasy dignity. Through his patient ministerings, and with an improbable emotional logic, he has proposed to Japan a route out from shame.

Notes

(1.) Moriyama titles, given in English in the text, correspond to untranslated Japanese originals. Here the respective works are: Nippon gekijo shashincho, Tokyo, Muromachi Shobo, 1968; Kariudo, Tokyo, Chuo Koronsha, 1972, and Taka Ishii Gallery, 1997; Shashin yo sayonara, Tokyo, Shashin Hyoronsha, 1972; Hikari to kage, Tokyo, Tojusha, 1982.

(2.) Inu no kioku, Tokyo, Asahi Shimbunsha, 1984; Inu no toki, Tokyo, Sakuhinsha, 1995; Inu no kioku-shusho, Asahi Shimbunsha, 1998.

(3.) In conversation with the author, January 1999.

(4.) See Alexandra Munroe, Japanese Art After 1945: Scream Against the Sky, New York, Harry N. Abrams, 1994, p. 19.

(5.) As quoted by Sandra Phillips in the title essay of Daido Moriyama: Stray Dog, by Sandra Phillips, Alexandra Munroe and Daido Moriyama, San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, and New York, D.A.P., 1999, p. 21.

(6.) Shomei Tomatsu, “The Original Scene,” in Tomatsu et al., Traces: 50 Years of Tomatsu’s Work, Tokyo Metropolitan Museum of Photography, 1999, p. 184.

(7.) In John Szarkowski and Shoji Yamagishi, New Japanese Photography, New York, Museum of Modern Art, 1974, p. 10.

(8.) Daido Moriyama, Shashin kara / Shashin e (From Photography to Photography), Tokyo, Seikyusha, 1995, p. 204.

(9.) Japan’s spirit at that moment is preserved in Kon Ichikawa’s splendid film on the games, which is no less truthful than Moriyama’s pictures or Oe’s stories–even though the government of the city of Tokyo commissioned it, and it gives us the opposite of alienation. See Tokyo Olympiad, directed by Kon Ichikawa, Tokyo, Toho Company, Ltd., 1965.

(10.) Daido Moriyama, “Shomei Tomatsu, the Man and His Work,” in Sandra Phillips et al, Daido Moriyama: Stray Dog, p. 45.

(11.) Kenzaburo Oe, Japan, the Ambiguous, and Myself, Tokyo, Kodansha, 1995, p. 120.

(12.) John Dower, Embracing Defeat: Japan in the Wake of World War II, New York, The New Press/W.W. Norton, 1999, pp. 156, 161.

All translations of writings by Daido Moriyama were very generously provided by Linda Hoaglund.

Leo Rubinfien is a photographer and the author of A Map of the East and 10 Takeoffs 5 Landings. He is a fellow of the International Center for Advanced Studies at New York University, and lived in Tokyo as a child.

EXPLORE ALL DAIDO MORIYAMA ON ASX

For more of American Suburb X, become a fan on Facebook and follow us on Twitter.

(© Leo Rubinfien, 1999. All rights reserved. All images © copyright the photographer and/or publisher