Sebastião Salgado and the wild poetry of the Amazon

The Brazilian photographer brings the amazing universe of the jungle to Madrid with ‘Amazônia’, the project that took him on a years-long exploration of this endangered ancestral world

Sebastião Salgado was traveling alone. He had documented the great migratory movements of the planet throughout 35 countries, always in solitude. Three Leica R6s (the same ones with which he immortalized the attack on Ronald Reagan or the burning of oil wells in Kuwait), two ostrich skin bags, good walking shoes and a Moleskine notebook (where he took exquisite notes for his photo captions). In the fall of 1997, I accompanied him on his reporting work on irregular migration routes between Africa and the coast of Cádiz in southern Spain, which were later included in his 2000 book Exodus. For 10 days we lived at a frantic pace to document the daily traffic of small boats that each day caused dozens of deaths. Every night brought a hellish situation, with migrants fighting for life over death. We hardly slept. Salgado was coming out of a severe illness, and his skull looked polished like a billiard ball, but we still spent our nights on patrol aboard Customs Surveillance helicopters, while our days were spent on Spanish Civil Guard boats patrolling the Strait of Gibraltar. We talked to many migrants, and Salgado encouraged them to fight. It was 10 breathless days. Salgado’s work earned him the Prince of Asturias Award in 1998.

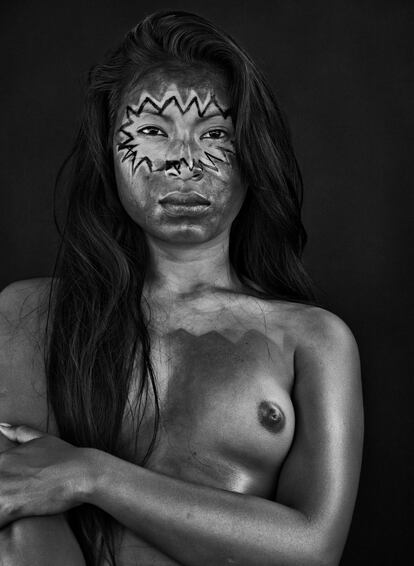

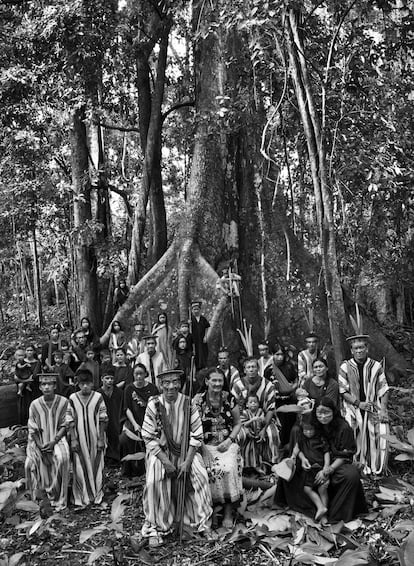

He is a very tough guy. Meticulous. Engaged. And that spirit is reflected in projects such as Amazônia: journeys through the Amazon jungle over several years to portray the ecological and human tragedy of the destruction of this critical green area of the world. It is an amazing window into an ancient and endangered world inhabited by 310,000 indigenous people from 169 ethnic groups who speak no fewer than 130 languages. “Through the power of images, we aspire to highlight the majesty of nature and the noble simplicity of the lifestyle of the indigenous population. We believe that humanity as a whole has the responsibility of caring for its common heritage,” explains the artist about this project, which now comes in the form of an exhibition in Madrid.

The exhibition Amazônia can be visited at Fernán Gómez Centro Cultural de la Villa, in Madrid, between September 13 and January 14, 2024.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition