The Bannock tribe were originally Northern Paiute but are more culturally affiliated with the Northern Shoshone. They are in the Great Basin classification of Indigenous People. Their traditional lands include northern Nevada, southeastern Oregon, southern Idaho, and western Wyoming. Today they are enrolled in the federally recognized Shoshone-Bannock Tribes of the Fort Hall Reservation of Idaho, located on the Fort Hall Indian Reservation. The Bannock are prominent in American history due to the Bannock War of 1878. After the war, the Bannock moved onto the Fort Hall Indian Reservation with the Northern Shoshone and gradually their tribes merged. Today they are called the Shoshone-Bannock. The Bannock live on the Fort Hall Indian Reservation, 544,000 acres (2,201 km²) in Southeastern Idaho.[8] Lemhi and Northern Shoshone live with the Bannock Indians.

Welcome to the Shoshone-Bannock Tribes Website! The Shoshone-Bannock Tribes are located in Southeastern Idaho. The tribal government offices and most tribal business enterprises are located eight miles north of Pocatello in Fort Hall. The Fort Hall Reservation was established by the Fort Bridger Treaty of 1868 as a 1.8 million acre homeland for the four distinct bands of Shoshone and one Northern Paiute band, the Bannock, that once inhabited this region. Between 1868 and 1932, the reservation landbase was reduced by more than two-thirds due to non-Indian encroachment on the land. Today, the reservation consists of 544,000 acres, nestled between the cites of Pocatello, American Falls and Blackfoot, and is divided into five districts: Fort Hall, Lincoln Creek, Ross Fork, Gibson and Bannock Creek. The tribes are proud to say that 96% of that land still remains in tribal and individual Indian ownership.

Bannock, North American Indian tribe that lived in what is now southern Idaho, especially along the Snake River and its tributaries, and joined with the Shoshone tribe in the second half of the 19th century. Linguistically, they were most closely related to the Northern Paiute of what is now eastern Oregon, from whom they were separated by approximately 200 miles (320 km). According to both Paiute and Bannock legend, the Bannock moved eastward to Idaho to live among the Shoshone and hunt buffalo. Traditional Bannock and Shoshone cultures emphasized equestrian buffalo hunting and a seminomadic life. The Bannock also engaged in summer migrations westward to the Shoshone Falls, where they gathered salmon, small game, and berries. They traveled into the Rockies each fall to hunt buffalo in the Yellowstone area of what are now Wyoming and Montana.

The Shoshone-Bannock Tribes are located on the Fort Hall Reservation in Southeastern Idaho, between the cities of Pocatello, American Falls, and Blackfoot. The Reservation is divided into five districts: Fort Hall, Lincoln Creek, Ross Fork, Gibson, and Bannock Creek. Currently, 97% of the Reservation lands are owned by the Tribes and individual Indian ownership. The Reservation was established in 1867 by President Andrew Johnson by Executive Order on June 14, 1867. The following year, on July 3, 1868, the tribal leadership signed the Fort Bridger Treaty, which affirmed that the newly established Fort Hall Indian Reservation would become the permanent home for the Shoshone and Bannock people. The Fort Hall Reservation was divided into five districts: Fort Hall, Lincoln Creek, Ross Fork, Gibson and Bannock Creek.

The Shoshones and Bannocks entered into peace treaties in 1863 and 1868 known today as the Fort Bridger Treaty. The Fort Hall Reservation was reserved for the various tribes under the treaty agreement.The Fort Hall Reservation is located in the eastern Snake River Plain of southeastern Idaho. It is comprised of lands that lie north and west of the town of Pocatello. The Snake River, Blackfoot River, and the American Falls Reservoir border the reservation on the north and northwest. The reservation was established by an Executive Order under the terms of the Fort Bridger Treaty of 1868. It originally contained 1.8 million acres, an amount that was reduced to 1.2 million acres in 1872 as a result of a survey error. The reservation was further reduced to its present size through subsequent legislation and the allotment process.

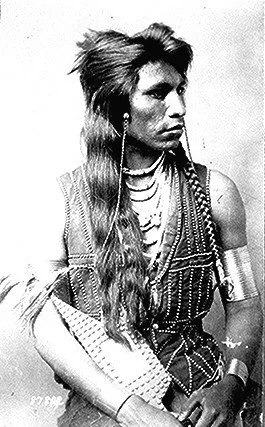

The Bannock Indians are a Shoshonean tribe who long lived in the Great Basin in what is now southeastern Oregon and Southern Idaho. Calling themselves the Panati, they speak the Northern Paiute Language and are closely related to the Northern Paiute people, so much so, that some anthropologists consider the Bannock to be simply one of the northern-most bands of the Northern Paiute. Early on, the Bannock subsisted primarily on fish and small game. They fished with harpoons, hand nets, and weirs built from woven willows. They also provided for their survival by gathering and using a number of plant foods. Primarily, they lived in teepees and small conical lodges made of sagebrush, grass, and woven willow branches. Later, they developed a horse culture and associated closely with the Northern Shoshone, and were a widely roving tribe. Although Shoshonean in language, they were generally described in early reports to more closely resemble the Nez Perce.

The Bannock tribe were nomadic hunter gatherers who inhabited lands occupied by the Great Basin cultural group. The tribe fought in the 1878 Bannock and the Sheepeater Wars. The names of the most famous chief of the Bannock tribe was Chief Buffalo Horn. The Bannock tribe called themselves the Panati and were closely related to the Northern Paiute people. The Bannock tribe were originally hunters, traders and seed gathers from the Great Basin cultural group of Native Indians. The Great Basin social and cultural patterns were those of the non-horse bands often referred to as the Desert Culture. These people were highly skilled basket makers and wove the baskets so closely that they would hold the finest seeds and even water. When they acquired the horse they moved to the hospitable lands and adopted the customs and culture of the Plains tribes. The Bannock are people of the Great Basin Native American cultural group. The geography of the region in which they lived dictated the lifestyle and culture of the Bannock tribe.

The Shoshone-Bannock Tribes of Fort Hall are comprised of the eastern and western bands of the Northern Shoshone and the Bannock, or Northern Paiute, bands. Ancestral lands of both tribes occupied vast regions of land encompassing present-day Idaho, Oregon, Nevada, Utah, Wyoming, Montana, and into Canada. The tribes are culturally related, and though both descend from the Numic family of the Uto-Aztecan linguistic phylum, their languages are dialectically separate. When the Northern Paiutes left the Nevada and Utah regions for southern Idaho in the 1600s, they began to travel with the Shoshones in pursuit of buffalo. They became known as the Bannocks. The Tribes generally subsisted as hunters and gatherers, traveling during the spring and summer seasons, collecting foods for use during the winter months. They hunted wild game, fished the region’s abundant and bountiful streams and rivers (primarily for salmon), and collected native plants and roots such as the camas bulb. Buffalo served as the most significant source of food and raw material for the tribes. After the introduction of horses during the 1700s, hundreds of Idaho Indians of various tribal affiliations would ride into Montana on cooperative buffalo hunts. The last great hunt of this type occurred in 1864, signaling the end of a traditional way of life.

Bannock Indian Culture and History

The Bannock Indians are a Native American tribe of the Great Basin region, particularly what is now Idaho, though they were a widely traveled tribe who also had outposts in parts of Oregon, Utah, Nevada, Montana, Wyoming, and British Columbia. The Bannocks are closely related to the Northern Paiute tribe, and speak a dialect of the Northern Paiute language. Today, most Bannock people live on the Fort Hall reservation in Idaho, where they have merged with their allies the Shoshones.

OUR BANNOCK WEBSITES

Paiute/Bannock Language

Language learning worksheets and directory of resources for the Bannock Indian language.

Bannock Facts for Kids

Questions and answers about Bannock culture.

Bannock Legends

Collection of Bannock Indian legends and origin stories.

MAPS OF BANNOCK LANDS

Language Map of the Numic Tribes

Maps showing the approximate locations of the Bannocks and their neighboring tribes.

Utah Tribal Map

State maps showing the location of the combined Shoshone-Bannock people.

BANNOCK TRIBAL AND COMMUNITY WEBSITES

Shoshone-Bannock Tribes

Official homepage of the Shoshone-Bannock Indians of Fort Hall Reservation.

Sho-Ban Tribal Enterprises

Homepage of a tribally owned economic consortium of Shoshone-Bannock businesses.

Rocky Mountain Tribal Leaders Council

Coalition of ten Indian tribes in Montana and Wyoming, including the Shoshone-Bannock Tribes.

Fort Hall Indian Agency

Website of the BIA office representing the Shoshone and Bannock tribes.

Shoshone-Bannock High School

Homepage of the Shoshone-Bannock tribal school.

Homepage of the Shoshone-Bannock casino.

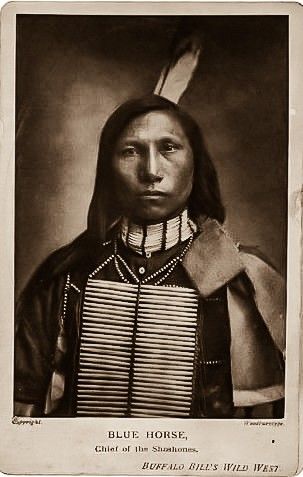

Bannock Indians (from Panátǐ, their own name). A Shoshonean tribe whose habitat previous to being gathered on reservations can not be definitely outlined. There were two geographic divisions, but references to the Bannock do not always note this distinction. The home of the chief division appears to have been south east Idaho, whence they ranged into west Wyoming. The country actually claimed by the chief of this southern division, which seems to have been recognized by the treaty of Ft Bridger, July 3, 1868, lay between lat. 42° and 45°, and between long. 113° and the main chain of the Rocky Mountains. It separated the Wihinasht Shoshoni of west Idaho from the so-called Washaki band of Shoshoni of west Wyoming. They were found in this region in 1859, and they asserted that this had been their home in the past. Bridger had known them in this region as early as 1829. Bonneville found them in 1833 on Portneuf River, immediately north of the present Ft Hall reservation. Many of this division affiliated with the Washaki Shoshoni, and by 1859 had extensively intermarried with them. In 1869 they were estimated as not exceeding 500, and this number was probably an overestimate as their lodges numbered but 50, indicating a population of about 350. In 1901 the tribe numbered 513, so intermixed, however, with the Shoshoni that no attempt is made to enumerate them separately. All the Bannock except 92 under Lemhi agency are gathered on Ft Hall Reservation, Idaho.

http://www.indigenouspeople.net/shoshoni.htm

Shoshone Literature

The Shoshone or Shoshoni (/ʃoʊˈʃoʊniː/ (![]() listen) or /ʃəˈʃoʊniː/ (

listen) or /ʃəˈʃoʊniː/ (![]() listen)) are a Native American tribe with four large cultural/linguistic divisions:

listen)) are a Native American tribe with four large cultural/linguistic divisions:

- Eastern Shoshone: Wyoming

- Northern Shoshone: southern Idaho

- Western Shoshone: Nevada, northern Utah

- Goshute: western Utah, eastern Nevada

They traditionally speak the Shoshoni language, part of the Numic languages branch of the large Uto-Aztecan language family. The Shoshone were sometimes called the Snake Indians by neighboring tribes and early American explorers.

Their peoples have become members of federally recognized tribes throughout their traditional areas of settlement, often co-located with the Northern Paiute people of the Great Basin.

The name “Shoshone” comes from Sosoni, a Shoshone word for high-growing grasses. Some neighboring tribes call the Shoshone “Grass House People,” based on their traditional homes made from sosoni. Shoshones call themselves Newe, meaning “People.”

The Shoshoni language is spoken by approximately 1,000 people today. It belongs to the Central Numic branch of the Uto-Aztecan language family. Speakers are scattered from central Nevada to central Wyoming.

The largest numbers of Shoshoni speakers live on the federally recognized Duck Valley Indian Reservation, located on the border of Nevada and Idaho; and Goshute Reservation in Utah. Idaho State University also offers Shoshoni-language classes.

Meriwether Lewis recorded the tribe as the “Sosonees or snake Indians” in 1805.

The Shoshone are a Native American tribe, who originated in the western Great Basin and spread north and east into present-day Idaho and Wyoming. By 1500, some Eastern Shoshone had crossed the Rocky Mountains into the Great Plains. After 1750, warfare and pressure from the Blackfoot, Crow, Lakota, Cheyenne, and Arapaho pushed Eastern Shoshone south and westward. Some of them moved as far south as Texas, emerging as the Comanche by 1700.

As more European-American settlers migrated west, tensions rose with the indigenous people over competition for territory and resources. Wars occurred throughout the second half of the 19th century. The Northern Shoshone, led by Chief Pocatello, fought during the 1860s against settlers in Idaho (where the city Pocatello was named for him). As more settlers encroached on Shoshone hunting territory, the natives raided farms and ranches for food and attacked immigrants.

The warfare resulted in the Bear River Massacre (1863) when US forces attacked and killed an estimated 410 Northwestern Shoshone, who were at their winter encampment. A large number of the dead were non-combatants, including children, deliberately killed by the soldiers. This was the highest number of deaths which the Shoshone suffered at the hands of United States forces.

During the American Civil War travelers continued to migrate westward along the Westward Expansion Trails. When the Shoshone, along with the Utes participated in attacks on the mail route that ran west out of Fort Laramie, the mail route had to be relocated south of the trail through Wyoming.

Allied with the Bannock, to whom they were related, the Shoshone fought against the United States in the Snake War from 1864 to 1868. They fought US forces together in 1878 in the Bannock War. In 1876, by contrast, the Shoshone fought alongside the U.S. Army in the Battle of the Rosebud against their traditional enemies, the Lakota and Cheyenne.

“You people are in big trouble.

That land doesn’t belong to you any more.”

“Maybe not,” Mike said, “but we belong to it.

You whites think everything is dead,

and you can just do what you want and the land doesn’t know.”

Shoshone Mike

Stories

“Ground Afire” is the meaning of the Indians’ name for what is now known as Death Valley. “And in the height of summer there is no better name for this sun-tortured trench between blistered ranges. But when a group of forty-niners [1849] blundered into it, they renamed it Death Valley.”

The valley and the high mountain ranges west and east of it are now called Death Valley National Monument. It is located in southeastern California and southwestern Nevada. Many square miles of the valley are below sea level–the lowest level in the Western Hemisphere.

More than 600 kinds of plants thrive in the valley. Its rocks make it a geologists’ paradise. And for everyone, “the great charm of the area lies in its magnificent range of color, which varies from hour to hour.”

Long, long ago, Indians used to say, this valley was beautiful and fertile. The people who lived there were ruled by a beautiful but capricious queen. One time she ordered them to build a mansion for her, one that would surpass any mansion ever built by their neighbours, the Aztecs.

For years, her people worked to make a palace that would please her. From places many miles away they dragged stones and logs. The queen, fearing that her age or an accident or an illness might prevent her from seeing her dream come true, ordered many of her people to assist in the work. Gradually, her tribe became a tribe of slaves.

The queen commanded even her own daughter to join those dragging logs and stones. When the noonday heat caused the workers to drag along slowly, with heads bowed, the queen strode angrily among them and lashed their naked backs.

Because royalty was sacred, the people did not complain. But when she struck her daughter, the girl turned, threw down her load of stone, and solemnly cursed her mother and her mother’s kingdom. Then, overcome by heat and weariness, the girl sank to the ground and died.

In vain, the queen lamented and regretted. All nature seemed to punish her. The sun came out with blinding heat and light. Vegetation withered. Animals disappeared. Streams and wells dried up. At last the queen had to give up her life; she died with high fever. There was no one to soothe her last moments, for her people, too, were dead.

The mansion, half-completed, stands in the midst of this desolation. Sometimes it seems to rise into view of people at a distance, in the shifting mirage that plays along the horizon.

It seems the l800’s thinking that the government

knows what is best for Indians still reigns.

Richard Boland, Timbisha Shoshone Tribal Administrator

To the Western Shoshone, storytelling ability was a highly regarded talent, as the stories were a primary method of educating the young about their culture and desired conduct within it.

References:

SHOSHONE TALES, collected by Anne M. Smith, assisted by Alden Hayes. University of Utah Press, 101 University Services Building, Salt Lake City, UT 84112, (800) 444-8638 ext 6771, (801) 581-3365. Illustrated, references, map. 188 pp.

CHIEF WASHAKIE

http://www.indigenouspeople.net/washakie.htm

Chief Washakie (c. 1798 – February 20, 1900) was a renowned warrior first mentioned in 1840 in the written record of the American fur trapper, Osborne Russell. In 1851, at the urging of trapper Jim Bridger, Washakie led a band of Shoshones to the council meetings of the Treaty of Fort Laramie (1851). Essentially from that time until his death, he was considered the head of the Eastern Shoshones by the representatives of the United States government.

The year of his birth is debated. A missionary in 1883 recorded the year of his birth as 1798, and later his tombstone was inscribed with the date 1804. Late in his life he told an agent at the Shoshone Agency that he had met Jim Bridger when he was 16. Interpolating from the age of Bridger when he first went into the wilderness, researchers have determined that Washakie was likely born between 1808 and 1810. During his early childhood, the Blackfeet Indians attacked a combined camp of Flathead and Lemhi people while the latter were on a buffalo hunt near the Three Forks area of Montana (where the Gallatin, Madison, and Jefferson rivers form the headwaters of the Missouri River). Washakie’s father was killed; his mother and at least one sister were able to make their way back to the Lemhis on the Salmon River in Idaho. In the melee of the attack, Washakie was lost and possibly wounded. According to some family traditions, he was found by either a band of Bannock Indians who had also come to hunt in the region, or by a combined Shoshone and Bannock band. He may have become the adopted son of the band leader, but for the next two-and-one-half decades (c. 1815-1840) he learned the traditions and the ways of a warrior that were typical of any Shoshone youth of that period.

Much about Washakie’s early life remains unknown, although several family traditions suggest similar origins. Washakie was born in 1798 to his mother Lost Woman, who was a Tussawehee (White Knife) Shoshoni by birth, and his father, Crooked Leg (Paseego), an Umatilla rescued as a boy from slave traders at Wakemap and Celilo in 1786 by Weasel Lungs, a Tussawehee dog soldier (White Knife) Shoshoni medicine man. Washakie’s father, Crooked Leg, was adopted into Weasel Lungs’ clan. There, Crooked Leg, would become a Tussawehee dog soldier (White Knife) Shoshoni, as he would meet and marry Weasel Lungs’ eldest daughter Lost Girl, later Lost Woman. Thus, Washakie’s maternal grandfather was Weasel Lungs. His maternal grandmother, Chosro (Bluebird)), was also Tussawehee by birth. Lost Woman’s younger sister, Washakie’s aunt was Nanawu (Little Striped Squirrel), the mother of Chochoco (Has No Horse), who was therefore a first cousin to Washakie. tu sert a rien le kikou

His prowess in battle, his efforts for peace, and his commitment to his people’s welfare made him one of the most respected leaders in Native American history. In 1878 a U.S. army outpost located on the reservation was renamed Fort Washakie, which was the only U.S military outpost to be named after a Native American. Upon his death in 1900, he became the only known Native American to be given a full military funeral.[4]

Washakie County, Wyoming was named for him. In 2000, the state of Wyoming donated a bronze statue of Washakie to the National Statuary Hall Collection. There is also a statue of Chief Washakie in downtown Casper, Wyoming. The dining hall at the University of Wyoming is also named after him. The current ghost town of Washakie, Utah was also named after him.

During World War II, a 422-foot (129 m) Liberty Ship built in Portland, Oregon, in 1942, SS Chief Washakie, was named in his honor. USS Washakie, a United States Navy harbor tug in service from 1944 to 1946 and from 1953 to 1975, also was named for him.[11]

Washakie was a hide painter. An epic 1880 painted elk hide at the Glenbow-Alberta Institute is attributed to him. The hide painting portrays the Sun Dance.[

“The white man, who possesses this whole vast country from sea to sea, who roams over it at pleasure and lives where he likes, cannot know the cramp we feel in this little spot, with the underlying remembrance of the fact, which you know as well as we, that every foot of what you proudly call America not very long ago belonged to the red man. The Great Spirit gave it to us. There was room for all His many tribes, and all were happy in their freedom.”

“The white man’s government promised that if we, the Shoshones, would be content with the little patch allowed us, it would keep us well supplied with everything necessary to comfortable living, and would see that no white man should cross our borders for our game or anything that is ours. But it has not kept its word! The white man kills our game, captures our furs, and sometimes feeds his herds upon our meadows. And your great and mighty government–oh sir, I hesitate, for I cannot tell the half! It does not protect our rights. It leaves us without the promised seed, without tools for cultivating the land, without implements for harvesting our crops, without breeding animals better than ours, without the food we still lack, after all we can do, without the many comforts we cannot produce, without the schools we so much need for our children.”

“I say again, the government does not keep its word!”

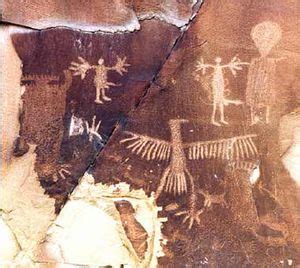

Important Shoshone Mythological Figures

Creator and culture hero of Shoshone mythology. Like other figures from the Shoshone mythic age, Wolf is usually represented as a man, but sometimes takes on the literal form of a wolf.

Wolf’s younger brother, Coyote is a trickster figure. Though he often assists his brother and sometimes even does good deeds for the people, Coyotes behavior is so irresponsible and frivolous that he is constantly getting himself and those around him into trouble.

Violent race of magical little people who were said to kill and eat people.

Mysterious and dangerous water spirits from the mythology of the Shoshone and other Western Indian tribes, water babies inhabit springs and ponds, and are usually described as water fairies who lead humans to a watery grave by mimicking the sounds of crying babies at night. Sometimes they are said to kill babies and take their place as changelings in order to attack their unsuspecting mothers. Water babies and their eerie cries are considered an omen of death in many Shsohone communities.

Shoshone Indian Folklore

Western Shoshoni Myths

Collection of Shoshoni Indian myths and legends.

Wolf Tricks the Trickster

Shoshoni legend about the origin of death.

The White Trail In The Sky

Shoshone legend about the exile of Grey Bear.

Queen of Death Valley

Shoshone legend about an ancient queen’s wickedness.

The Wolf, the Fox, the Bobcat and the Cougar:

Legend about four animal spirits that helped the Shoshone-Bannocks defeat the warlike Little People.

Eastern Shoshone Tribe

#14 North Fork Road

P.O. Box 538

Fort Washakie, WY 82514

(307) 332-3532

(307) 332-3055

est@easternshoshone.org