Irish Myths is reader-supported. When you buy through links on our site, we may earn a small affiliate commission.

I admit it. I am one of *those* people — a person whose favorite holiday is Halloween, who still dresses up every year despite being in my thirties, and who loves, loves, LOVES, carving pumpkins. Maybe too much.

A couple of years ago, after watching far too many pumpkin carving competition shows on TV, I decided I was done with templates, done with two-dimensional jack-o’-lantern designs. I bought my first “professional” carving kit, complete with wood-handled sculpting tools. The following year, I upgraded to an even more professional carving kit. My results have been…meh. (See for yourself.)

But I’m not giving up! I am admittedly addicted to the art of pumpkin carving, and more specifically, to the art of creating jack-o’-lanterns with big ole teeth and grotesque expressions. For years, I believed it was my Massachusetts upbringing that instilled this passion in me. Growing up a stone’s throw away from Salem (of witch trials fame), Halloween was always a big deal.

But what if my love of jack-o’-lanterns goes deeper than that?

What if it’s in my blood?

The Irish Origins of the Jack-O’-Lantern

Pssst. You can watch a video adaptation of this article right here👇 (Text continues below.)

Listen, my children, and you shall hear, of the midnight meddling of Stingy Jack, from whom the jack-o’-lantern derives its name. Or so the story goes.

Here’s the most common version of the 18th-century Irish folktale:

A grumpy bastard of a blacksmith by the name of Stingy Jack invites the devil for a drink but refuses to pay (hence, the “stingy” descriptor). He convinces the devil to shape-shift into a coin to cover the tab. But when the devil obliges, Jack sticks the coin in his pocket. And much to the devil-coin’s dismay, there is a silver cross in that pocket, preventing him from returning to his original form. A deal is struck. Jack sets the devil free and, in return, the devil agrees A) to bar Jack from entering hell when he dies, and B) to leave Jack alone for a year.

A quick aside: This seems like a bad deal. And it is a bad deal — because guess what? A year later, the devil comes back to mess with Jack. Only Jack is ready for him. He convinces the devil to climb a tree so he might enjoy a delicious piece of fruit. Once the devil is up in the tree, Jack carves a cross into the trunk. The devil can’t come down. Another (bad) deal is struck, although this one does have the advantage of being slightly less bad than the previous one. Jack frees the devil in exchange for ten years of peace.

Jack dies. (Don’t be sad. He was an asshole.) The devil, true to his word, refuses to let Jack into hell. God, meanwhile, refuses to let Jack into heaven. So, what is Jack’s fate? To wander forever in eternal darkness, of course. But because the devil is not totally heartless (wait…), he tosses Jack a lump of burning coal from hell so he can have a bit of light. Jack carves out a turnip and sticks the coal inside, creating a lantern. Hence, “Jack of the Lantern,” which is later shortened to “Jack O’Lantern.”

The rest, as they say, is folklore.

By which I mean: There’s a lot more to the story.

For starters, there’s the beginning of the story, which most sources (the Irish Times notwithstanding) neglect. In it, Jack, acting out of character, helps an old man on the side of the road. Twist! The old man is an angel in disguise. The angel, who is clearly a fan of One Thousand and One Nights, grants Jack three wishes. And this is where Jack’s true colors (and lack of imagination) begin to shine through.

Wish #1: anyone who sits in Jack’s chair will be stuck to the spot.

Wish #2: anyone who takes a bough from Jack’s sycamore tree will be stuck to the spot.

Wish #3: anyone who borrows Jack’s tools will be stuck to the spot.

The angel reluctantly grants these wishes, but he makes a mental note that this Jack fellow, when the time comes, should not be allowed into heaven. Eventually, the devil comes to claim Jack, but as we already know, that plan does not go swimmingly. Granted, things don’t turn out too swell for ole Jackie boy either. To quote the Irish Times:

It’s fitting that a character trapped in an earthly purgatory should become the lasting symbol of Halloween, a time when people are as wont to offer a “trick” as a “treat”. The character of Jack, a figure who doesn’t fit into heaven or hell, is unusually complex for a figure from a folk tale.

This begs the question:

How are we supposed to feel about Stingy Jack? Should we be satisfied that this mean-spirited blacksmith got his comeuppance? Or, like the talkative Irish uncle quoted in an 1836 issue of the Dublin Penny Journal — a man who claims to have seen Jack with his own eyes — should we pity the jack-o’-lantern’s namesake?

If you knew the sufferings of that forsaken craythur, since the time the poor sowl was doomed to wandher, with a lanthern in his hand, on this cowld earth, without rest for his foot, or shelter for his head, until the day of judgment… oh, it ‘ud soften the heart of stone to see him as I once did, the poor old dunawn, his feet blistered and bleeding, his poneens (rags) all flying about him, and the rains of heaven beating on his ould white head.

source: The Irish Times

Bogged Down by the Details: The Original Meaning of “Jack-O’-Lantern”

So, case closed, right? We carve scary faces into vegetables on Halloween because an 18th-century Irish folk antihero once shoved a hell-coal into a turnip. Makes perfect sense. The jack-o’-lantern is a symbol of Stingy Jack’s suffering. It’s the perfect decoration for commemorating this awful, crafty man.

Or…not.

Because another interpretation holds that the purpose of creating jack-o’-lanterns is not to celebrate Stingy Jack, but to protect oneself from him. To quote journalist Kayla Hertz (writing for IrishCentral):

This legend is why people in Ireland and Scotland began to make their own versions of Jack’s lantern by carving grotesque faces into turnips, mangelwurzels, potatoes, and beets, placing them beside their homes to frighten away Stingy Jack and other wandering evil spirits and travelers.

If both of these explanations feel a bit tenuous, it’s because…they are. The truth is, the story of Stingy Jack was not invented to explain the origin of carved vegetable lanterns (which, as we’ll explore later, go back thousands of years). Instead, the story was invented to explain a different phenomenon altogether: ignis fatuus.

Also known as will-o’-the-wisps, fairy lights, fool’s fire, and — yes — jack-o’-lanterns, ignis fatuus refers to the incredibly eerie (but entirely natural) flickering of lights that occurs over peat bogs and marshlands. It’s caused by the combustion of gases that are released from decomposing organic matter.

Remember that talkative Irish uncle quoted in the previous section? He told his Stingy Jack story while gazing out at a peat bog, observing the ignis fatuus. That’s the explanation he gave for what he was seeing. And at the time, it was a common one.

According to Nathan Mannion, senior curator of Dublin’s Irish Emigration Museum, the ignis fatuus often seemed like “a floating flame that would move away from travelers.” He goes on to say:

If you were to try to follow the light, you could go into a sinkhole or bog, or drown. People thought it was Jack of the Lantern, a lost soul, or a ghost.

source: National Geographic

To make matters even more convoluted, there is another possible origin for the term “jack-o’-lantern,” one that eschews ghosts and devils and flaming bog farts and replaces them with something far more mundane: night watchmen. You see, in 17th-century Britain, “Jack” was a common catch-all for someone whose name you didn’t know (sort of like the “John Doe” of its time). So an anonymous night watchman would sometimes be called a “Jack of the Lantern,” or “Jack O’Lantern.”

Add to this the 18th-century tradition out of Worcestershire, England known as the “Hoberdy’s Lantern,” which could be made by hollowing out a turnip, carving a face on the outside, and sticking a candle inside, and it’s possible that the jack-o’-lantern is actually a British innovation.

Gasp! I can hear my Irish great-grandfather rolling in his grave — assuming he isn’t roaming the eternal darkness of an earthly purgatory (one can never be sure).

That being said, the Irish origin for the jack-o’-lantern is still widely held by scholars and historians. And the main reason for that has to do with the Emerald Isle’s Celtic history.

The Celtic Connection: Samhain and the Cult of the Head

In Celtic enclaves of northern Europe (e.g. Ireland, Scotland, Wales, the Isle of Man, Cornwall, Brittany) the carving of human faces into round fruits and vegetables has been going on for thousands of years. It is a tradition, according to our pal Mannion of the Irish Emigration Museum, that likely evolved from the Celtic custom of head veneration, wherein the severed heads of one’s enemies were taken as war trophies.

One needs only to peruse the myths of ancient Ireland to see the significance that was placed on heads. (Not, like, literally placed on top of heads… you know what I mean.) For example, there’s the story of the Ulster hero Cúchulainn, the Hound of Culann, who returned from his first-ever battle with three heads hanging from his chariot, as well as “nine heads in one hand and ten in the other, and these he brandished at the hosts in token of his valor and prowess.” Meanwhile, in “The Destruction of Da Derga’s Hostel,” the warrior Conall pours water into the mouth of the High King of Ireland Conaire Mór’s severed head — and the head thanks him.

History confirms this Celtic obsession with the head. Ancient historians Livy and Diodorus Siculus both recount instances of Celtic warriors hanging the severed heads of their slain foes from the necks of their horses. Siculus further notes that especially distinguished foes were given the royal treatment: their heads were embalmed in cedar oil and displayed with pride to visitors. This practice is also reflected in the ancient Irish tradition of creating “brain-balls,” wherein the brains of enemies were hardened with lime and used as slingshot projectiles.

Lovely.

So why were heads so important to ancient Celtic peoples, including the Irish? To quote historian Peter Berresford Ellis, author of A Dictionary of Irish Mythology and The Celtic Empire:

The ancient Irish revered the human head as, indeed, did all ancient Celtic societies. It was in the head and not in the heart that they seemed to locate the souls of men and women… Archaeological finds give full corroboration to this cult.

source: A Dictionary of Irish Mythology

During the Celtic festival of Samhain, when it was believed that souls from the Otherworld were able to cross over to the land of the living, the cult of the head reached a fever pitch. Armed with a plethora of root vegetables from the recent harvest (as Samhain marked the end of one pastoral year and the beginning of the next), ancient peoples carved frightening faces in an effort to ward off restless souls.

There was also a fire element to the festival of Samhain. On the night of October 31st, when the festival began, all fires burning across Ireland and other Celtic countries were supposed to be extinguished, and could only be rekindled thereafter from a ceremonial fire lit by druids. To facilitate this practice, a good deal of lanterns were needed to transport the coals. Hence, those carved root vegetables ended up serving a practical purpose in addition to a symbolic one. To quote Mannion:

Metal lanterns were quite expensive, so people would hollow out root vegetables. Over time people started to carve faces and designs to allow light to shine through the holes without extinguishing the ember.

source: National Geographic

Of course, now we’re faced with a chicken and the egg problem: Did the ancient Irish turn their carved faces into lanterns, as I suggested earlier, or did they carve faces into their lanterns, as Mannion asserts?

It’s hard to say.

But what I can tell you definitively is that when the Christians arrived on the scene, they hijacked the festival of Samhain for their own purposes, turning November 1st into “All Saints’ Day” a.k.a. “All Hallows.” Hence, the evening prior became known as “All Hallows Eve,” which is celebrated today as Halloween. The Celtic cult of the head was largely forgotten, and the vegetable lanterns with their frightening faces were reinterpreted, by some, as representations of Christian souls in purgatory.

The aforementioned Stingy Jack, of course, a man forever stuck between heaven and hell, fits that Christian interpretation to a T. So in addition to being used to explain the phenomenon of ignis fatuus and, later, to explain the origins of the jack-o’-lantern, the story of Jack was employed “as a cautionary tale, a morality tale,” according to Mannion, who elaborates: “Jack was a soul trapped between two worlds, and if you behaved like he did you could end up like that, too.”

The Americanization of the Jack-O’-Lantern: From Turnips to Pumpkins

If the history of the jack-o’-lantern wasn’t already convoluted enough for ya, we have a whole ‘nother era to explore — arguably the jack-o’-lantern’s golden age:

The Age of Pumpkins.

In the midst of and in the decades following the Great Famine, millions of Irish immigrants fled to North America, and with them they brought their ancient Samhain/Halloween tradition of vegetable carving. While originally accustomed to using turnips, beets, and potatoes as their canvases, these Irish immigrants easily adapted their art to the more rotund and versatile pumpkin — a gourd native to the New World.

The first mention of the pumpkin jack-o’-lantern ostensibly appears in Nathaniel Hawthorne’s 1835 short story, The Great Carbuncle, in which a band of adventurers seeks out a legendary gem. To quote Hawthorne:

Hide it under thy cloak, say’st thou? Why, it will gleam through the holes, and make thee look like a jack-o’-lantern.

Given that The Great Carbuncle was written before the massive influx of Irish immigrants to North America, however, it is possible that Hawthorne is not actually referencing a pumpkin jack-o’-lantern in this passage, but the phenomenon of ignis fatuus. (Remember, that was the original meaning of the word.) That’s not to say, however, that an earlier group of Irish immigrants couldn’t have introduced the “carved vegetable lantern” meaning of jack-o’-lantern to Hawthorne. The matter is up for debate.

According to the Irish Times, the first definitive reference to a pumpkin jack-o’-lantern carved in celebration of Halloween occurred in 1886, when a Canadian newspaper, the Daily News, reported the following:

The old time custom of keeping up Hallowe’en was not forgotten last night by the youngsters of the city […]There was a great sacrifice of pumpkins from which to make transparent heads and face, lighted up by the unfailing two inches of tallow candle.

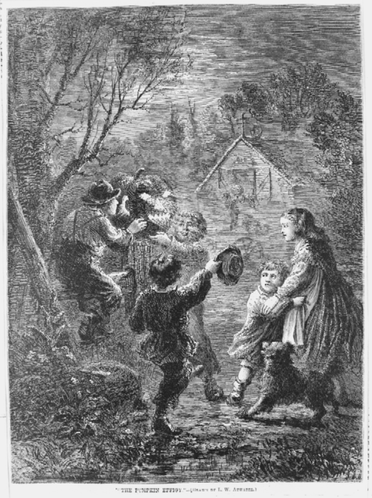

However, it should be noted that the first image of a pumpkin jack-o’-lantern appeared nearly two decades before this in the November 23, 1867 issue of Harper’s Weekly. It was published alongside an article titled “A Pumpkin Effigy,” but — and this is an important but — the article did not refer to the carved gourd as a “jack-o’-lantern,” nor did it reference Halloween.

By the turn of the century, the pumpkin jack-o’-lantern had become the symbol of Halloween in North America. While once intended to scare off unwanted nocturnal visitors, these incandescent decorations are now most frequently used (despite their often grotesque appearances) to welcome visitors and convey a sense of joviality and community.

To quote Cindy Ott, author of Pumpkin: The Curious History of an American Icon:

At Halloween, you don’t go up to someone’s house unless they have a jack-o’-lantern. It’s about cementing a community, projecting good values, neighborliness. The pumpkin and jack-o’-lantern take on those meanings, too.

Final Thought: The Neverending Story

The jack-o’-lantern is an art form that has multiple possible origins (re: Celtic head veneration, an Irish folktale about an asshole, anonymous English night watchmen), multiple symbolic meanings (re: it represents the lantern of a notorious trickster, or the fires of Samhain, or Christian souls stuck in purgatory), and multiple functional purposes (re: transporting sacred coals, warding off evil spirits, welcoming guests). Which of these are the “correct” readings of the jack-o’-lantern’s history? Perhaps none of them. Perhaps all of them. That’s the beauty of a good story.

To quote Jessica Traynor, writing for the Irish Times:

Stories rarely stay the same over time. They change, evolve, become symbol and metaphor – especially when people move to new places and different myths and cultures intermingle.

Here’s to myths and cultures continuing to intermingle.

*raises pumpkin sculpting tool*

Want to learn the rest of the Samhain story? Check out…

Samhain in Your Pocket

Perhaps the most important holiday on the ancient Celtic calendar, Samhain marks the end of summer and the beginning of a new pastoral year. It is a liminal time—a time when the forces of light and darkness, warmth and cold, growth and blight, are in conflict. A time when the barrier between the land of the living and the land of the dead is at its thinnest. A time when all manner of spirits and demons are wont to cross over from the Celtic Otherworld. Learn more…

Irish Monsters in Your Pocket

In the Ireland of myth and legend, “spooky season” is every season. Spirits roam the countryside, hovering above the bogs. Werewolves lope through forests under full moons. Dragons lurk beneath the waves. Granted, there’s no denying that Samhain (Halloween’s Celtic predecessor) tends to bring out some of the island’s biggest, baddest monsters. Prepare yourself for (educational) encounters with Irish cryptids, demons, ghouls, goblins, and other supernatural beings. Learn more…

Neon Druid: An Anthology of Urban Celtic Fantasy

“A thrilling romp through pubs, mythology, and alleyways. NEON DRUID is such a fun, pulpy anthology of stories that embody Celtic fantasy and myth,” (Pyles of Books). Cross over into a world where the mischievous gods, goddesses, monsters, and heroes of Celtic mythology live among us, intermingling with unsuspecting mortals and stirring up mayhem in cities and towns on both sides of the Atlantic, from Limerick and Edinburgh to Montreal and Boston. Learn more…

More the listenin’ type?

I recommend the audiobook Celtic Mythology: Tales of Gods, Goddesses, and Heroes by Philip Freeman (narrated by Gerard Doyle). Use my link to get 3 free months of Audible Premium Plus and you can listen to the full 7.5-hour audiobook for free.