What is Harlequin Ichthyosis?

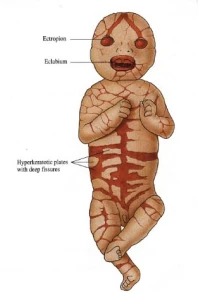

Photo courtesy of http://www.pediatriconcall.com

Harlequin Ichthyosis is a rare genetic disorder that affects the integumentary system. Infants with this condition are born with hard, thick skin that cracks and splits apart leaving them highly susceptible to infection, dehydration, and temperature instability. Often, infants with Harlequin Ichthyosis have limited movement in their extremities due to the thickness of their skin, which may hinder the infants’ ability to perform essential functions such as eating and breathing. Facial features such as the eyelids, nose, mouth, and ears may also be distorted, especially in the first few weeks of life.

The prefix “ichthy” is taken from the Greek word for fish, referring to the scaly appearance of the skin. Each year, over 16,000 babies are born with some form of Ichthyosis. Harlequin Ichthyosis is the rarest and most severe form of Ichthyosis. The term “harlequin” comes from the characteristic clown’s smile seen in newborn infants with this condition, caused by excess tension from the skin that pulls the mouth wide open. The exact prevalence of this condition is unknown, but it is estimated to be less than 1/1,000,000. The risk of mortality is high during the neonatal period, especially in rural areas that lack access to highly specialized neonatal care. With early diagnosis and treatment, more infants with this condition are surviving into adulthood.

What’s happening inside the body?

In 2005, Harlequin Ichthyosis was linked to a mutation in the ABCA12 gene. This gene is essential for the normal development of skin cells in the body because it holds the instructions for making special proteins called “ATP-binding cassette transporters”. The purpose of these transporters is to assist with fat (lipid) transport to the outermost layer of the skin.

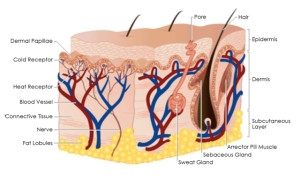

Photo courtesy of http://www.whiteteamedspa.com

The skin is has three layers called the hypodermis, dermis, and epidermis. The hypodermis, or innermost layer of the skin, is made up of connective tissue and fats. The dermis contains the hair follicles and the sweat glands. The epidermis, which is the layer of skin that is primarily affected in Harlequin Ichthyosis, provides a barrier for the body. The epidermis is essential in thermoregulation and preventing infection. People with Harlequin Ichthyosis typically either have an absence of the ABCA12 gene, or they have a version of the protein that is too small to properly transport lipids. Since lipids are essential for the normal development of skin, the inadequate lipid transport prevents the skin from forming an effective barrier. Normal skin is elastic, smooth, moist, and intact. In comparison, the skin of an infant born with Harlequin Ichthyosis has hard, thick scales that pull apart, creating deep fissures in the skin that leaves the body vulnerable to infection. Without lipids, the skin loses its elasticity, causing it to become tight. This tightness can cause distorted facial features, difficulty breathing, and restricted movement of the extremities. The body requires extra calories to maintain normal function, so physical development may be delayed due to the amount of energy the body has to place into creating skin.

What are the causes of Harlequin Ichthyosis?

Harlequin Ichthyosis is caused by a mutation in the ABCA12 gene. It is inherited in an autosomal recessive pattern, which means that both parents need to be carriers of the mutated gene. Typically, carriers of this condition do not show any signs or symptoms, so they are unaware that they carry the gene. Genetic counseling is available for people with a family history of Harlequin Ichthyosis, as there is a 25% risk of reoccurrence among carriers.

What symptoms should I be looking for?

Common symptoms of Harlequin Ichthyosis include

Photo courtesy of http://www.hindsdale86.org

- Hard, thick skin separated by large fissures at birth

- Severe scaling erythroderma as the infant grows

- Distorted facial features: ectropion (eyelids everted), eclabium (mouth forced due to skin tension), ears appearing to be misshapen/missing, nasal hypoplasia

- Alopecia (sparse hair)

- Small, swollen hands/feet

- Prematurity

- Hypernatremia (high sodium levels in the blood)

- Dehydration

- Temperature dysregulation

- Frequent infections

- Difficulty breathing

- Poor suck reflex and difficulty feeding

- Delayed physical development

- Short stature

Are there any tests that confirm Harlequin Ichthyosis?

Genetic testing is the more definitive way to diagnose Harlequin Ichthyosis. This form of testing can be done both prenatally and postnatally. Early diagnosis is crucial to improving the outcomes of infants born with Harlequin Ichthyosis. With access to high level neonatal care at birth, these infants have a much higher chance of surviving.

Prenatal diagnosis of Harlequin Ichthyosis helps families and health care providers to prepare for the special needs that an infant with this condition will have. Parents with a family history of Harlequin Ichthyosis are encouraged to see a genetic counselor. Ultrasonography may show features suggestive of Harlequin Ichthyosis such as ectropion, eclabium, diffuse scaling, flattened ears, and nasal hypoplasia. For a more definitive test, fetal DNA can be drawn via amniocentesis or chorionic villus sampling to test for mutations in the ABCA12 gene.

DNA testing is used for diagnosis postnatally. In addition to DNA testing, many health care providers initially diagnose the condition based on its clinical presentation. A skin biopsy of cutaneous tissue may show certain characteristic features, however the biopsy is not typically clinically necessary.

What are the treatment options?

The treatment of an infant born with Harlequin Ichthyosis is complex and requires the work of a multidisciplinary team. It involves medications, supportive therapy, infection control, and daily skin care. Treatments include

- Medications

-Retinoid administration within the first week of birth (Etretinate or Acitretin 1 mg/kg body weight) to help accelerate

the shedding of skin

-Isotretinoion 0.5mg/kg/day may be given orally in the first few days to increase limb movement, skin pliability, sucking

reflex, and eyelid closing - Supportive Therapy

-Place infant in a high-humidity incubator

-Umbilical lines are often needed for monitoring and treatment

-Insert a feeding tube as needed for decreased suck reflex or feeding intolerance

-Initiate IV fluids to prevent dehydration

-Lubricate the eyes with sterile lubricant if eyelids are forced open - Infection Control

-Antibiotic treatment as the thick skin peels off in the first few weeks of life

-Daily skin assessment to identify any areas of impaired skin integrity - Skin Care

-Bathe infants at least twice daily for at least 30 minutes

-Apply bland, fragrance-free lubricant to skin frequently

*Note: Please visit the “Links and Resources” page for a list of references used for this post