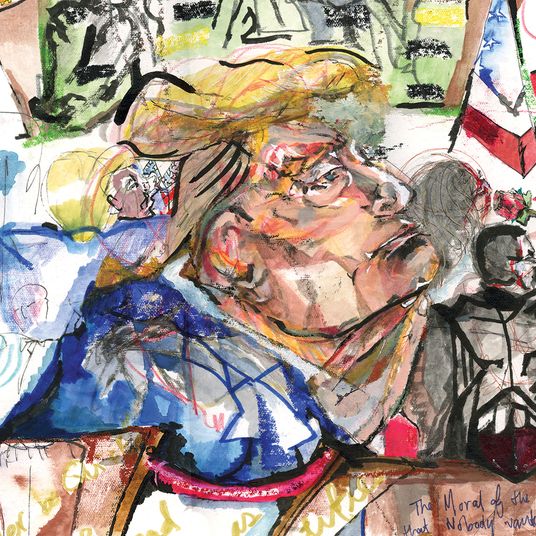

Fifteen years ago today, an Iraqi journalist stood up in the middle of a press conference in Baghdad and shouted in Arabic, “This is a farewell kiss from the Iraqi people, you dog!” and then proceeded to hurl his shoes, one after the other, at then-President George W. Bush. The gesture by the journalist, Muntadhar al-Zaidi, had dire effects on his own life — a risk he was well aware of beforehand — but it lives on in the public imagination worldwide as perhaps the most effective individual protest against America’s bloody and ultimately disastrous invasion and occupation of Iraq.

Al-Zaidi flung his footwear just weeks after United States voters had given Barack Obama a landslide victory to succeed Bush, in no small part on the strength of the position that Bush had launched a “dumb war.” If Bush thought he might somehow repair his outgoing 24 percent approval rating with a press conference alongside an apparently stable and benevolent Iraqi leader, he was mistaken — or was at least thwarted by al-Zaidi’s viral protest.

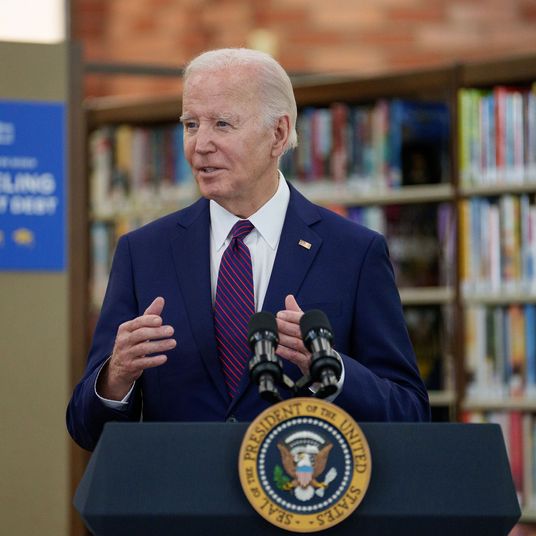

But beyond putting a U.S. president on his heels and relegating his Iraqi partner to a hapless goalie trying to block the second shoe, the event presaged an era of American presidential politics that has been rife with indignities: Think Representative Joe Wilson shouting “You lie!” to President Obama, the U.N. General Assembly laughing uproariously at President Trump, and Marjorie Taylor Greene belting “Liar!” to President Biden.

“I don’t think something like that would seem out of place today, in a world where people feel emboldened to express their displeasure with pretty much anybody without hesitation,” said Jennifer Loven, who covered the 2008 press conference as the chief White House correspondent for the Associated Press. “The fact that that was so unusual just 15 years ago seems kind of weird to me now.” In the months and years afterward, dozens of copycat incidents occurred around the world with angry citizens, inspired by al-Zaidi, firing shoes at political figures.

Lost in the coverage of the theatrics, though — and the subsequent memeification of the moment — was the fact that al-Zaidi’s life changed forever in that moment. The Iraqi journalist, now 44 and living in Baghdad, was sentenced to three years in prison (spending nine months there) and describes being tortured. He claims to have been blacklisted from the media industry and today struggles to make a living as a consultant. For this story, he offered a detailed account of his thinking, his actions, and the punishment he endured as a result of his encounter with Bush. Loven and others who were at the infamous press conference also shared their memories and impressions. They were unanimous in thinking in the heat of the moment that the first airborne shoe wasn’t merely a protest but a bomb that would blow them all up — and unanimous in being unnerved by what happened to al-Zaidi afterward.

Jennifer Loven, chief White House correspondent for the AP in 2008: These secret trips were still remarkable for us in the White House press pool, even by the end of Bush’s tenure. You go to Andrews Air Force Base in the dark of night, turn in your phone and computer, board the plane in the hangar with all the windows down, and you’re not allowed to tell anybody that you’re going, all that cloak-and-dagger stuff that surrounded one of these trips. So naturally, when all those protocols are in place, you just get a heightened sense of, Oh, we must be in danger. And of course there was danger, as there always was with these war-zone trips.

President Bush had a lot he wanted to say about his legacy before he left office. And so he was taking this trip, which had some very practical aspects to it around the signing of the U.S.-Iraq Status of Forces Agreement, but it was also a bit of a good-bye lap. I wouldn’t call it a victory lap. But I do remember that Bush’s relationship with the Iraqi prime minister, Nouri al-Maliki, was important to him. Al-Maliki wasn’t universally loved, but he was doing a reasonably good job by that time, and I think there was a sense of pride around that. So you kind of take the wins you can take. That was probably part of the calculation of taking the trip, that this was a guy you could feel good standing next to. Did we know where this was all going? No, but probably if you asked the Bush team at the time, they’d say they could feel like, “We didn’t make a giant mistake. It turned out well in the end.”

Olivier Knox, White House correspondent for Agence France-Presse in 2008: We were watching to see if there would be a Status of Forces Agreement signed between Bush and Nouri al-Maliki, basically the rules of the road for American troops in Iraq for Bush’s successor, Barack Obama. But there was also a symbolic portion — Bush sort of summarizing the American experience in Iraq and giving his farewell.

Muntadhar al-Zaidi, chief correspondent for Al-Baghdadia TV in 2008 and the man who threw his shoes at President Bush: Leading up to that 2008 press conference, what I had seen was my country invaded and occupied without justification. Maybe the Iraqi people were desperate to get rid of Saddam. Regardless, I didn’t want to see it done by foreign forces. My people were humiliated. The American forces killed people in the street. They scared and intimidated my people when they raided their houses in the middle of the night. So the Americans behaved in a savage way.

As a journalist, I covered many stories of rape by American soldiers. There was one child that was raped and killed and then the American soldier accused the insurgents.

Knox: Obviously, Bush’s trip to Iraq was going to look very different from inside Iraq as it would look from inside the United States, even though by then it was pretty well established that the president had misled the country into war, no weapons of mass destruction would be found, and we were all keenly aware of the enormous civilian and economic toll. Which is in part why AFP had local reporters as well because it was always envisioned that the final product would be some kind of a combination story from the two perspectives.

I spoke to the local AFP reporter after the shoes were thrown. “What just happened?” I asked. “Oh that’s Muntadhar al-Zaidi,” he said. “He’s been saying for six months that if he ever ends up in the same room as George W. Bush, he’ll throw his shoes at him.” Which raises the question: If the Iraqi press corp knew, why didn’t Iraqi security?

Al-Zaidi: I didn’t tell anybody what I was going to do. But I did plan it, which included considering the consequences. I even recorded my will, thinking that I could be shot and killed by the American guards. Or, short of death, enduring torture, solitary confinement, and defamation. I even decided to wear slip-ons so they were easy to take off. My initial plan was to only throw one. But if I missed my target and had an opportunity to throw another, it would be easy to throw the second one. So I was ready physically and spiritually.

On the way into the press conference, the Iraqi security was like I hadn’t seen before. We were scanned and searched. Iraqi security even took my shoes off and checked them. When they did that, I thought to myself, That’s the weapon I have, and smiled.

Right before entering the room with Bush, two American guards were randomly frisking members of the Iraqi press pool, which I took to be a great indignity. If you are in the U.S. and the Russian president comes, American journalists aren’t checked by Russian guards. One of them, after searching the journalists in front of me, slapped them on the butt, which I took as a great insult. I prayed to God that he would not search me, for fear that I would get angry and lose control before I had a chance to carry out my plan. He did not search me.

Then I was in the room of the press conference with my crew: a cameraman and a reporter. I took off my ring, which had sentimental value, and gave it to my cameraman. I said, “Listen, give it to my brother and say hi.” I didn’t say why. Then I gave him my wallet. Then I gave him my money and my identification.

My first impression of Bush when he entered the room was a devil without horns. I saw him as a weak person. I was thinking, How come this weak person waged wars in Afghanistan and Iraq and killed many people, including Americans, and destroyed the American economy? My impression was that he was a nobody. I felt sorry for my people, for the American people, that this nobody caused all this damage.

When the time came, I did think about not reacting. I thought to myself, Why do you want to do this? You’re still young. You’re chief correspondent of a TV channel. You have money. You have a car. You’re not yet married. You have a future. Why do you want to sacrifice all of this? At that moment, my adrenaline got low. My heartbeat got low. For a few moments, I felt relaxed. But suddenly, I had another thought to myself: If I don’t do it, I will consider myself a coward all my life. If I don’t do it now, I will betray the blood and sacrifice of my people. Then the adrenaline went back up.

Bush was talking, saying he would have a dinner with Maliki after the press conference. And I said to myself, I have a good dinner for you. You’ll eat my shoe!

When Bush finished talking, I stood up and yelled, “I want to give you a good-bye kiss from the Iraqi people, you dog!”

I wanted to give him a warning. This is what we call the ethics of knights, or knight’s honor.

Evan Vucci, staff photographer for the Associated Press in 2008: Al-Zaidi was behind me to the right. I heard him yelling. I turned to the noise, thinking it was a suicide bomber, and got off like two frames with my camera.

Knox: All of a sudden, we saw something solid and black sail over our heads. My first thought was, Is that something that’s going to go boom? We all sort of hunched down. Covering the White House means you become very aware that the last place you want to be is between the Secret Service and a threat to the president of the United States.

Loven: I notice in my peripheral vision a black thing going really fast right next to my head, and I freak out. Leading up to that, there are so many security measures. You know, when you travel by helicopter from one part of the Green Zone to another, you wear a bulletproof vest. There are lots of messages sent about “This is not a safe place.” So in my mind, I thought bomb immediately. So I dive to the floor and my shit scatters everywhere. And Bush ducks and then another one comes. It was chaos.

Al-Zaidi: The room was filled with armed men. This confrontation was not a game. First, I felt satisfaction, but then I felt the pain. After I threw the second shoe, one cameraman pulled me by my belt and put me down. Then I was attacked by the guards of Prime Minister Maliki and one American guard. I was screaming, insulting George Bush, yelling, “You are a dog, you killed my people!” And they shut my mouth. They beat me, they broke my nose, and they broke my teeth. I think I even swallowed a tooth.

Knox: Iraqi security were beating him. All I could see was a dogpile with fists flying.

Loven: They were beating the shit out of him. He was first beaten up by his peers, then Iraqi security. All I could remember was total mêlée behind me. But I was in reporter mode, just trying to do my job. So once I realized it was a shoe, I called my desk, and there’s people sitting there waiting for me to dictate news alerts to them. I call and say, “You have to put this on the wire: Man throws shoe at Bush.” And they’re like, “No, we’re not putting that on the wire, that’s ridiculous.” I’m like, “No, you have to. It’s a really big deal!” They didn’t understand. It was just weird. “Man throws shoe at Bush” doesn’t tell you very much. I explained it and then they did put it on the wire.

Vucci: All the photographers in the room were freaked out. None of us got that photo of Bush and the shoe in the same frame. We were all worried. This is a once-in-a-lifetime photo, and it happened in front of you and you missed it.

When they were beating him up, I was concerned about getting the photos I did have out of the room. I was worried that the Iraqis beating up al-Zaidi were embarrassed and would want to destroy the image. So I switched the cards in my camera and put the card with the images in my pocket.

Dana Perino, the press secretary, ended up getting a black eye (a boom mic fell on her). In all the chaos, I look behind the podium and I see the shoe on the ground. And I’m like, Man, that would be an awesome souvenir.

(Perino, now a host on Fox News, declined to be interviewed for this story.)

Knox: And then they dragged al-Zaidi behind closed doors.

Loven: The Iraqi journalists were apologizing to Bush, and he and Maliki played it off. Bush was even a little jokey about it. And he talked about the ability to protest. The content of what he said was the right thing to say. “That’s what happens in free societies,” the president said.

Knox: There was fresh blood on the carpet.

Loven: There was a trail of the blood that led down the hall. And, I mean, you could hear the guy screaming.

Vucci: I remember being unnerved by the screaming. It was loud. Like, Okay, it’s probably under control. You don’t gotta beat the guy. He’s no threat. Why do you need to continue to do that?

Al-Zaidi: They took me outside the room. They tied me with cable, and Maliki’s nephew beat me with a pipe. He broke my foot. I knew it was Maliki’s nephew because he was his personal guard. He always stood behind Maliki.

The Iraqi journalists who were apologizing to Bush were pro-occupation, pro-Maliki. They were propagandists. They took bribes to write stories praising the prime minister. So I was not surprised that they were against me.

I was surprised by the western journalists. They were hearing me being beaten and tortured. But none of them asked the president or the prime minister a question about me being beaten and tortured.

Loven: That day, facts were hard to come by. We could hear him screaming, but we wouldn’t have any way of knowing in the moment what was actually happening. I’m sure we asked about it either later in the trip or back in the U.S.

Eight days after the Baghdad press conference, a reporter asked Deputy Press Secretary Tony Fratto at a White House press briefing, “Is the White House at all concerned about reports by the brother of this Iraqi journalist who is being held for throwing his shoes at the president? His brother says, in visiting the journalist in jail, he sees signs he’s been tortured, missing a tooth, cigarette burns on his ears —”

Fratto responded, “He’s in the hands of the Iraqi system. I don’t have anything more on the shoe thrower. I think it’s been explored extensively, and I have nothing new for you.”

Knox: At the Baghdad press conference, we had no firsthand indication that while al-Zaidi was being treated roughly, he was being tortured.

Vucci: If I was in a position to show Iraqi security doing that to that man, I would have absolutely shown that. My job is to document the world around me. There’s just no way for me to actually see it. I couldn’t get out of the room. But I do remember that after they subdued him, it should have stopped. That’s just human decency.

Knox: We were focused on the president. The shoe throwing completely redefined the trip. Bush knew this entire trip was going to be boiled down to that one act of defiance. It was no longer about President Bush sending a symbolic message or grappling with a Status of Forces Agreement. It became about a very angry journalist throwing his shoes at the president of the United States in a gesture of loathing. And one that we were familiar with because years earlier, when the marines pulled down the Saddam statue, Iraqi citizens lined up to pound the statue with their shoes. We were familiar with the cultural message there, the importance that it was a shoe and not a reporter’s notebook.

Al-Zaidi: A judge at the trial said, “You attacked and insulted a guest of our country. There’s a law against that.” I said, “We are Arabs, we are known for generosity. But the law doesn’t apply with Bush because he didn’t come as a guest. He came to Iraq by force. He invaded.” Based on my argument, the judge asked the prime minister’s office if Bush had been invited. The prime minister’s office replied that he was, and I was given my sentence — three years in prison for assaulting a foreign head of state during an official visit.

The just outcome would have been putting George Bush in prison, not me. I would ultimately spend nine months in prison, three of those months in solitary confinement. A very small cell that basically only fit my body. Each day is like a year. I was not allowed to talk to anyone. And only allowed to go to the bathroom three times a day. Sometimes I peed in a water bottle. I got through it with yoga, working out. I prayed. I’m a Muslim, but I’m against the Islamic Party. They’re medieval.

While in prison, I did find out about the statue of my shoes that was erected. The government tore it down the next day. I was honored that Iraqi society supported me but was laughing at how the government was afraid of a shoe statue.

When I was released, the first statement I made was “I’m a free man now, but the nation is still in a prison.”

More on George W. Bush

- Trump Didn’t Hijack Reagan’s GOP; It Was Never Fully His

- Trump Accuses George H.W. Bush of Hiding Papers in a Bowling Alley

- George W. Bush Iraq-Ukraine Gaffe Raises Unanswerable Questions