Meet Kurt Wenner the Master of Anamorphic Art

By James Buxton

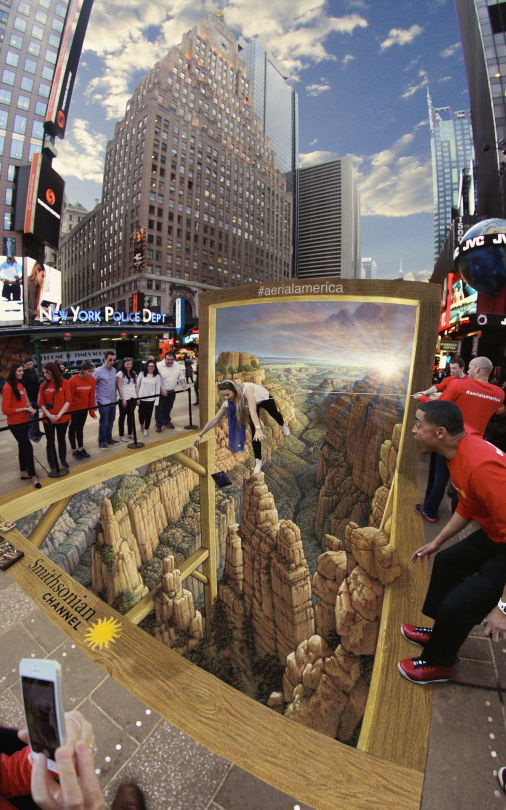

Widely acknowledged as the inventor of 3D anamorphic pavement art, Kurt Wenner went from working at NASA to opening up portals to other dimensions on the street with a piece of chalk. Since the early ‘80s, the U.S. artist has travelled extensively, bringing the secrets of Sacred Geometry and the Renaissance to life on the sidewalks of cities around the world. Gifted with extraordinary technical skill and the vision and determination to see his illusions come to life, Wenner has been the subject of a National Geographic documentary, created art for the Pope and developed his own style of anamorphic perspective, Wenner’s Geometry. I caught up with him to discover the secrets behind his mind-bending art.

When I was in Rome and Venice last year, I noticed anamorphic work was on the ceilings of cathedral frescoes as opposed to on the ground. I’m interested in the way you studied Renaissance art and explored ancient texts to gain an insight into theories of proportion and perspective and applied it to the streets. Did you have any epiphanies during your research and what was the most important discovery you made that has influenced your work?

Actually, it would have been an easy job merely to turn the ceiling geometry upside-down. The problem was in the viewing angles. The angle of view necessary for the pavement work was nearly three times that of a baroque ceiling. My first photos of the pavement works were photo-mosaics. I would stitch about 12 photos together to capture the pavement work. Then I figured out I could use a fisheye lens to get a single clean image. The fisheye lens has the same curved geometry of the back of the human eye. I realized that when I composed a work in fisheye perspective and projected it across the pavement surface, the projection was hyperbolic. This was a new form of perspective that addressed many of the issues artists struggled within the Renaissance and Baroque periods.

Could you talk a bit about these issues, and why you chose the sidewalk as your canvas as opposed to a wall?

My first (traditional) drawings on the pavement were mostly done on the Via del Corso in Rome, right across the street from the Italian Parliament. I earned on an average day about three times my NASA salary just with the tips thrown in the buckets. The lifestyle was fabulous — I had unlimited funds to study and travel with. It took 10 to 15 years for 3D pavement art to take hold and become interesting to the corporate world and therefore a possible full-time occupation. It may never have happened had it not been for the development of the Internet and social networking.

How does the environment affect your work?

In the early years it mostly affected the works because they were constantly being damaged by rain, sun and wind. A quote from my book reads: “Making a street painting is a lot like constructing a sand castle: while working on one part, another part is eroding… Street painting is a constant reminder that art is about process rather than product.” Now the major importance of the environment is that it appears in the final photographic image (along with the public). I therefore seek to cite the work so that image, public, and environment combine to tell a story.

Illusion is a major factor in your work. Why you find illusion so fascinating and what does it allow you to communicate?

In a general sense, illusion calls into question the nature of human perception. This is always a fascinating topic because we labor under intense misconceptions as to how we experience the world visually. Illusions poke fun at these misconceptions, but in fact, if there were no misconceptions there would be no illusions. In a more specific way, illusion is what allows me to combine the work, the audience and the environment into a single image. It is the combination and juxtaposition of these elements that is central to my work.

You have created hundreds of art works around the world. Which works are you most proud of and why?

I am partial to my “Dies Irae” because it was my first signature work of 3D pavement art and brought the form into existence. I like my darker works such as the series of contemporary “hells.” I am proud of my very large works such as the one I did for Greenpeace. The works I designed to be executed by teams of artists, such as the “Last Judgement,” “The Circus Parade,” and more recently the Guinness Book world record “Megalodon Shark” have given me a lot of pleasure.

You are widely acknowledged as the creator of anamorphic 3D art, what do you think is the future for this form of art?

My feeling is that relatively few young people today are drawn toward collecting artworks as physical artefacts. They seem to be very un-materialistic. What they do buy are things like iPhones and computer games. These are essentially tools that promise interaction with others rather than “things” to collect. It could be that the interactive aspect of the artwork needs to be maintained even in the form of fine art.

Source: perrier

240 notes

hiitsrosee liked this

andreym17 reblogged this from perrier

katievalicenti-blog reblogged this from perrier

katievalicenti-blog reblogged this from perrier thewongdynasty reblogged this from perrier

unclearwhy liked this

unclearwhy reblogged this from perrier

parallelfourths reblogged this from lichardrewis-blog

parallelfourths reblogged this from lichardrewis-blog lichardrewis-blog reblogged this from foreverxxinfinite

jawrain liked this

jawrain liked this  jawrain reblogged this from miss-ill-ustrations

jawrain reblogged this from miss-ill-ustrations miss-ill-ustrations reblogged this from tdalitt

miss-ill-ustrations liked this

maddiquin liked this

alucior liked this

captainexcelsior reblogged this from perrier

nisanth liked this

katakurimy liked this

vanpari reblogged this from perrier

vanpari liked this

naadedei liked this

naadedei liked this llexxis-blog liked this

twodifferentspaces liked this

koolcidss liked this

s4irene liked this

heliodorog liked this

simplyafterdeath-blog liked this

realpestilence liked this

realpestilence liked this perrier posted this

- Show more notes