As well as working overseas, the AANS could serve at hospitals at home in Australia. The problems of these home hospitals during wartime made themselves evident very early; with drugs and dressings being in short supply, as well as continued changes in staffing. The shortness of the notice given by the military authorities when they called up doctors, or nurses, for war service caused particular difficulty.[i] The Brisbane General Hospital (now the Royal Brisbane) experienced huge staffing deficits.[ii] Most of the senior staff and many of its former trainees had enlisted. By the end of 1914 Matron Grace M. Wilson, Sisters Linda G. Andrews, Constance M.Keys, Christense Sorenson (who later became General Matron of the Brisbane General), Charge Nurses Stella Zita Lyons, sisters Myrtle and Marjorie Wilson, Julia Hart, Mary E Fisher, Gertrude Nye and numerous others had enlisted.[iii] Their absence placed the hospital under enormous strain, as the remaining staff struggled with an increasing patient load against the obstacles of inadequate equipment, deteriorating buildings, and decreasing finances.[iv]

Finding suitable venues that could house returned injured and sick soldiers in the earlier part of the war years was quite an issue. In 1914 the Defence Department asked the Brisbane Hospital Committee whether accommodation could be offered to sick soldiers from the expeditionary camps, subsequently 50 beds were made available for soldiers and sailors.[v]

A government order in June 1915 created military general hospitals in each Australian state to meet the medical needs of injured or sick returned servicemen. In these hospitals the patients were seemingly under military discipline. More than 360 AANS nurses worked in home hospitals for several months as a prerequisite to their appointment to serve with the AIF overseas. This experience enabled them to understand the aftermath of war wounds and the illnesses from the front, as well as military systems, ranks and etiquette.[vi]

The Hospital with a View

Main building of Kangaroo Point Military Hospital, Brisbane, 1916. Alwynne Guy Elliot. John Oxley Library, State Library of Queensland.

In The Queenslander article, 22 May, 1916, “Our Wounded Boys: Accommodation need in Brisbane.” The article stated that 200 soldiers were returning from the front and then appealed to the patriotism of its readers to assist with providing “any houses or other suitable buildings as soon as possible”. The premier Digby Denham at this time inquired about transforming the Kangaroo Point Immigration Depot into a military hospital.[vii]

I shall consult with the military authorities’ tomorrow morning, and if they consider the building suitable it will be placed at their disposal. In the meantime I am inquiring how best to provide for the State’s requirements in respect to immigrants who arrive from time to time. I estimate that in the four wards there would be accommodation for 100 wounded. Under extreme pressure we have had as many as 160 persons in the building, but I do think that it would be considered proper to attempt to provide beds for more than 100 wounded in the four wards.[viii]

Following Premier Digby’s suggestion to utilise this building for the war effort, on 10 June, 1915 the military authorities approved turning it into the major military hospital for the Brisbane area. Thus, the 6th Australian Military Hospital otherwise known as Kangaroo Point Military Hospital (subsequently Yungaba after WWII), was originally an immigration depot. It was an ornate building that was designed by J.J. Clark to attract migration from the United Kingdom and Europe to Brisbane. With the introduction of Labour’s White Australian Policy and the impact of the war on travel halted migration during this period. [ix] The Queensland Railways, who had set up their own patriotic fund to aid their railworker’s on the front, contributed substantial amounts into building extra wards for the 6 AMH. In 1915, at the cost of £400, the Railway committee endowed 16 beds to the hospital known as the ‘Railway Ward’ which was opened 26 August, 1915. However, with the increased demand for rooms for the returned soldiers, the Railway committee contributed for an additional ward of 23 beds and the building will be a “hut with ornate design, having a tiled roof, practically open air, and maybe arranged so inmates maybe able to observe the river”.[x] At the cost of £1263, it opened 26 January, 1916 and contained 25 beds rather than the proposed 23. It was considered to meet the current standards and could easily compete with hospitals in Britain.[xi]

A very descriptive article on the sights around the hospital when the first wave of soldiers had returned on the Monday evening, written 21 July, 1915 in the Brisbane Courier is worth replicating:

One retuned soldier stated:

We had a good feed when we got here, a warm bath each, and then turned in, and slept like tops.

On Tuesday morning:

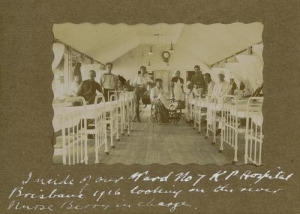

The men were sitting on the veranda, all looking bright and cheerful.

In the same article, an unknown woman also illustrated vividly describes hospital:

There are three wards, capable of providing for 250 men. Two of them are in readiness, and the largest one is occupied by those who returned on Monday evening. The ward is loft, very airy, scrupulously clean, well lighted, and well ventilated. The walls have been painted white, and the conditions are antiseptic. Along the walls and down the centre are rows of small iron bedsteads with their pure white furnishings, each bed being covered with a white sheet, in the centre of which is placed a large red cross and near the foot a large ‘Q’. The cross and the Q are stitched…at the end of the room hung warm blankets, dressing gowns, and blanket waist coats…At the rail of each bed was hung one of the white washers knitted by the children in schools, towels, handkerchiefs, shirts and pyjamas-all supplied through the red cross.[xii]

A Queensland nurse who served exclusively on the home front and was stationed at the 6 AMH was future Royal Red Cross 2nd class recipient, Matron Emily Elizabeth Bishop.[xiii] Matron Bishop trained at the Brisbane Hospital and a few years after the Australia Federation had been a part of a team that was entrusted to build a reserve of trained medical staff that was to be available for duty at base hospitals and stationary field hospitals in times of emergency.[xiv] On 1 May, 1915, Bishop had taken over as principal matron of the 1st Military District after her colleague Grace M. Wilson embarked for service overseas. On 15 September, 1915 Bishop was appointed to the 6th Australian Military Hospital where she remained until after the war had ended.[xv] In a Brisbane Courier article on September 1915, Bishop was quoted to have said of the hospital:

[The Hospital] was advanced in preparedness and equipment of those in the South. {She thought} the location ‘ideal’.[xvi]

The Kangaroo Point Military Hospital always sought to improve standards and facilities. A 1916 news article mentions an opening of a recreation hall for the soldiers.[xvii] However, in an article written at the end of the war on 11 November, 1918 mentioned when more than 7000 men a year had passed through the building, and even though it was a cheerful place, it was described as ‘gloomy and desolate looking’.[xviii] May 1919, saw an outbreak of influenza in Brisbane, and it was thought to have originated at Kangaroo Point Military Hospital. Whilst, this was refuted by the doctor of the time Dr Sutton, by June 1919, most of the patients had been transferred to the military hospital at Enoggera, which was considered to be more up-to-date.[xix]

Railway Ward Building no.6 Military Hospital. Kangaroo Point. Queensland State Archives, Digital Image ID 26741;

Huts at Kangaroo Point Military Hospital Brisbane 1916. Taken by Alwynne Guy Elliot. John Oxley Library, State Library of Queensland.

Inside the ward at Kangaroo Point Hospital, Brisbane, 1916.Alwynne Guy Elliot. John Oxley Library, State Library of Queensland.

The Modern Technical Wonder

The Commonwealth authorities established the no.13 (later changed to no.17) Australian General Hospital at the old concentration camps and paddocks at the Enoggera Military base. This was to relieve the Brisbane General Hospital of all the serious cases of sick and injured soldiers.[xx] The No.17 Hospital had two divisions, the first being the Clearing hospital, where sick soldiers with ordinary ailments or mild accidents, were looked after unless they had serious complications which necessitated transfer to the second division the bases General Hospital. In 1915, during its infancy phase and rush to accommodate, the Clearing Hospital was situated away from the base, in one article it is described:

There is a little hill off the beaten track that escapes notice….On entering the gates one sees a ‘street’, the right side of which is occupied by tents …the other [side] by galvanised huts, each of which represents a hospital ward.[xxi]

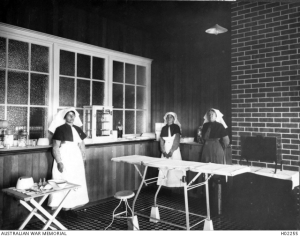

Buildings which were meant to be the new headquarters of the permanent artillery force, were converted into a large hospital base. By May 1916, the new Clearing Hospital had been built and it was considered ‘the most modern institution of its kind’. Situated on an elevated slope looking over the firing range, it remained isolated from the other encampments ensuring containment and purity of air. The main hospital had two wings, one for the medical officer’s quarters and the other for the commanding officer and staff. The nurses were housed in a separate two story building. The main building had two levels that could hold 161 beds or 200 in an emergency. It had verandas at the front and back which contained comfortable chairs, intended for the patients at the convalescent stage. Sheds in the paddock originally planned to be stables, were converted into places of recreation for the convalescing patients. All of the wards were equipped with modern equipment of the day. [xxii]

The technology of the No.17 at the time was considered impressive. There was an operating room situated in the lower part of the building that held a couple of operating beds and a sterilising machine that was kept working all day. Electric bulbs were powered by a specially generated current from two engines of 28 horsepower located in an outhouse, which lit up the entire hospital. Another modern technology was the use of the septic tank, to help reduce the spread of disease.[xxiii]

A section of a ward in the 13th Australian General Hospital at Enoggera. From left to right are: Private W Temple, Sister R A Skyring (left rear) and Sister Homewood. Bed patients are on both sides of the ward.

ENOGGERA, QUEENSLAND. C. 1917. A CORNER OF THE OPERATING THEATRE AND SOME OF THE STAFF AT THE ARMY CAMP CLEARING

The Idyllic Retreat

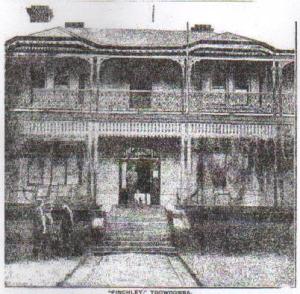

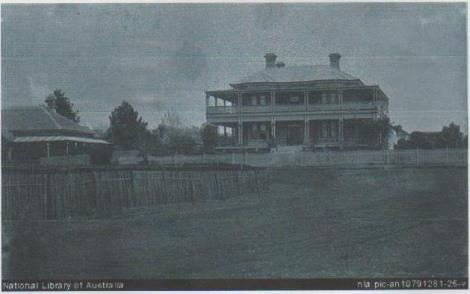

In 1916, the old residence of Dr and Mrs Spencer Roberts in Toowoomba, was lent to the Military authorities for the term of the war and was converted into the No.4 Auxiliary Hospital, and was known as the Finchley Convalescent Hospital. This grand two-storied brick building had balconies and verandas, which kept the rooms well ventilated. It stood well back from the street, and was surrounded by large shade trees. The electric light was installed, as well as other conveniences such as a cooking range and hot water in the kitchen. The second floor had large linen presses, and accommodation for the staff. There was a laundry building with a well contained laundry, the garden had tennis courts, rose buses, garden sheds, a cow pen, and fowl houses.[xxiv] The first batch of 24 convalescents arrived within a fortnight. It was a place of recuperation for the soldiers, with an emphasis on comforts, such as a piano, gramophone and records, musical instruments, and games were funded by the Railway Committee and Red Cross.[xxv] Finchley was known as a place of entertainment and merriment. Every Saturday it had evening parties that became quite the institution with many artists, both amateur and professional, dropping in to entertain the men.[xxvi] In November 1916, Finchley was ‘gazetted’ by the military as No. 9 Australian General Hospital, and it became a more disciplined place to which many in residence, the locals, or those who had visited, felt the loss of atmosphere.[xxvii]

After the war and after the last soldier had been discharged from the hospital, Finchley remained under military authority until early 1918. It was reported to be idle with over grown weed and looking neglected. There was a push to keep it as a place for soldiers without homes, friends and family, or at least place of care. Rather, Dr and Mrs Spencer Robert resided there and entertained with parties which was announced in the social columns’ well into late 1920s. This grand house was sadly demolished in 1965.

Was the home of Dr and Mrs Spencer Roberts. Lent out to the military for the term of the war. National Leader, 24 August,1917. In the photo three soldiers stand to the left of the stairs, whilst two stand on top in front of the door.

The Tennis lawns at “Finchley”. To the left of the picture is a group of soldiers. Between the lawns and the house were rose gardens, green houses and a great spreading of shade trees.

Finchley Auxillery Hospital, Toowoomba. photos taken by C.W Gallagher, 1916. The Queenslander, 23 March, 1916.

Queensland Training Hospitals

Brisbane Children’s

Brisbane General Hospital (now the Royal Brisbane)

Bundaberg Hospital

Cairns Hospital

Charters Towers Hospital

Coast/Cairns Hospital

Cobar District

Diamantina District Hospital

Gladstone Hospital

Gympie Hospital

Hillcrest Private Hospital, Rockhampton

Ipswich Hospital

Mackay District Hospital

Maryborough Public Hospital

Mater Misericordiae Hospital, Brisbane.

Mount Morgan Hospital

Peak Down’s Hospital, Clermont.

Ravenswood Hospital

Rockhampton Children’s

Rockhampton General.

Roma General

St. Dennis Private Hospital, Toowoomba.

St. Helen’s Private Hospital, Brisbane.

St.Mary’s Private Hospital, Ipswich.

Toowoomba Hospital

Townsville Hospital

Warwick Hospital

________________________________________________________________________________________

[i] Peter Rees, The Other Anzacs

[ii] D. C. Fison, The History of Royal Children’s Hospital, Brisbane. Brisbane: [S.n.], 1970, 3.

[iii] Helen Gregory, A Tradition of Care: A History at the Royal Brisbane Hospital (Brisbane: Boolarong Publications, 1988), 52.

[iv] Helen Gregory, 52.

[v] Ibid., 57; D.C Fison, History of Royal Children’s Hospital, 14.

[vi] Peter Rees, The Other Anzacs : Nurses at War 1914-18 ( Crows Nest, N.S.W.: Allen & Unwin, 2008),

[vii] “Our Wounded Boys” The Queenslander, 22 May 1915, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article22297244 (accessed October 23, 2014).

[viii] Ibid.

[ix] Delene Cuddihy, The Story of Yungaba (Brisbane, Queensland: Queensland State Library, 2006). Video source; Approval of expenditure in connection with fitting up of Immigration Depot as a Military Hospital, 10 June 1915, Queensland State Archives, Digital Image ID 24668.

[x] Report of General Railway Patriotic Fund, c 1917, Queensland State Archives, Digital Image ID 26741; “The Railway Ward: New Structure Proposed,” The Brisbane Courier, 1 October, 1915, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article20055198.

[xi] Report of General Railway Patriotic Fund, c 1917, Queensland State Archives, Digital Image ID 26741

[xii] “The Returned Soldiers,” in The Brisbane Courier, 21 July, 1915, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article20050869.

[xiii] Helen Gregory, 56.

[xiv] Ibid., 53.

[xv] “Woman’s World,” The Brisbane Courier, 14 February, 1920, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article20415974 (accessed October 13, 2014).

[xvi] “Military Hospital: Visit by the Governor and Lady Goold-Adams,” The Brisbane Courier, 17 September, 1915, http://nla.gov.au/nla-news-article20079072 (accessed October 16, 2014).

[xvii] “Recreation Hall Opened,” The Brisbane Courier, 12 April, 1916, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article20124048 (accessed October 21, 2014).

[xviii] “Kangaroo Point Hospital,” Cairns Post, 11 November, 1918, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article40306491

(accessed October 15, 2014).

[xix] “Kangaroo Point Military Hospital,” The Brisbane Courier, 28 June, 1919, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article20370831 (accessed October 15, 2014).

[xx] “Tending the Wounded,” The Brisbane Courier, 20 May, 1915, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article20043787 (accessed October 16, 2014).

[xxi] “The Clearing Hospital,” The Brisbane Courier, 18 Oct 1915, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article20089473 (accessed October 14, 2014).

[xxii] Ibid.

[xxiii] “New Military Hospital,” Cairns Post, 18 May 1916, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article40030732 (accessed October 14, 2014).

[xxiv] “No. 4 Auxiliary Hospital,” The Brisbane Courier , 1 Mar 1916, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article20077772 (accessed October 16, 2014).

[xxv] “Toowoomba Military Hospital,” The Brisbane Courier, 13 Mar 1916, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article20085261 (accessed October 16, 2014).

[xxvi] “Items of Interest,” National Leader , 10 Nov 1916, <http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article132393982 (accessed October 16, 2014).

[xxvii] “Toowoomba Military Hospital,” The Brisbane Courier, 16 Nov 1916, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article20113896 (accessed October 16, 2014).

Some of this information is particularly relevant to my research as support and I was wondering what year this information was added to the site and by whom? Thank you

LikeLike