Not a Day Without a Line is the last of four exhibitions organised as part of the Renaissance Queens’ two-year project, which began in May 2016. Since then, more than three thousand people have visited our exhibitions in the Old Library. Featuring bawdy poems, scholarly annotations, liturgy redacted and re-added, mysterious ciphers, hand-coloured books and unique bindings, this final exhibition celebrates some of the most extraordinary discoveries made during the Renaissance Queens’ cataloguing and outreach project.

Our previous three exhibitions have begun with a focus on a particular person or collection. Not a Day Without a Line began life rather differently, starting instead with the desire to showcase some of the exciting and unique discoveries made over the course of the cataloguing project. With no shortage of these, the first step – the curation of objects – was an enjoyable and fairly straightforward task. But every good exhibition requires a unifying theme. How did we land upon the common thread that holds the exhibition together?

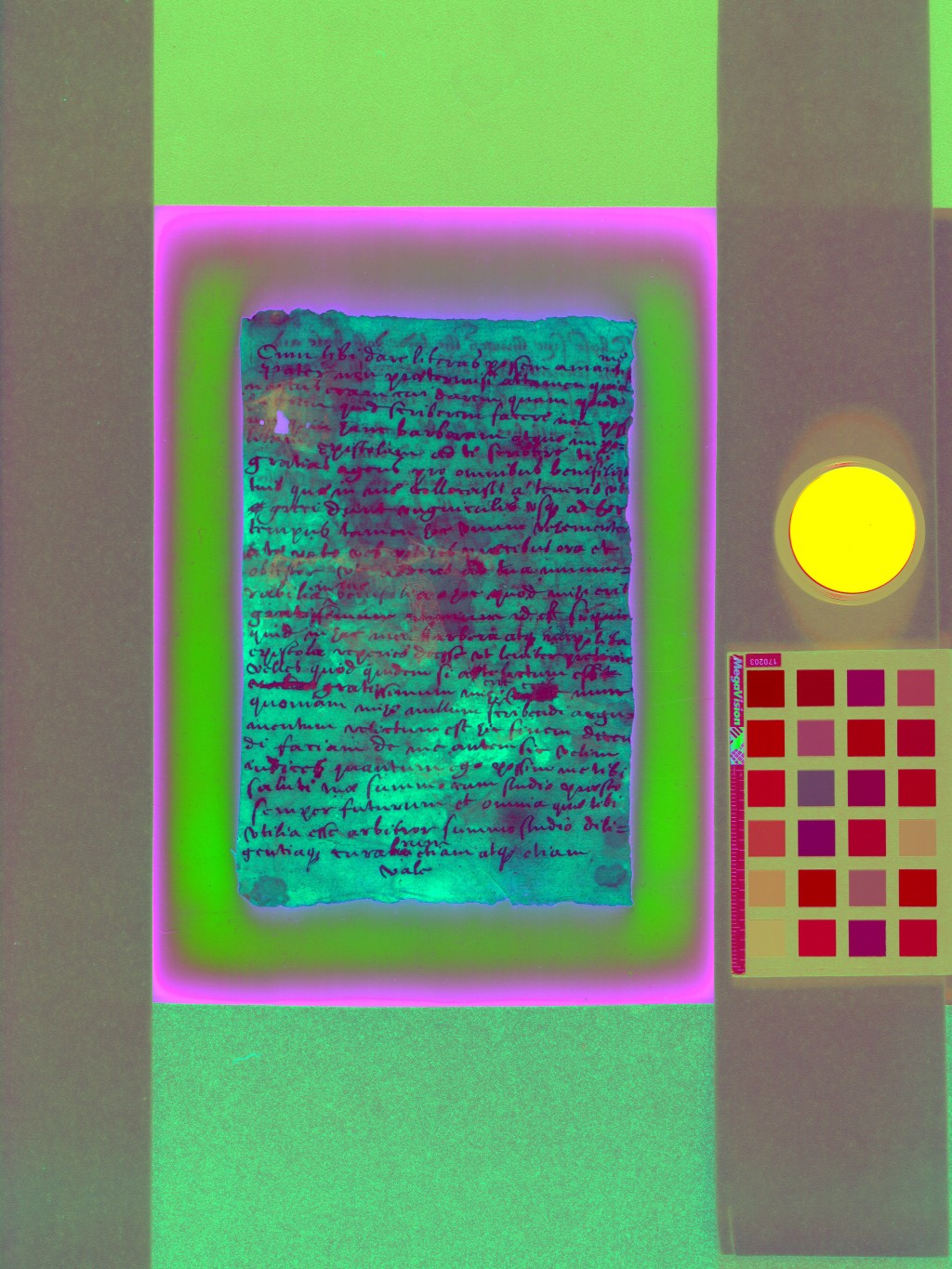

As a scholarly library, and one that was at the heart of the Renaissance humanist movement, with its emphasis on “active reading” (interrogating the text by comparison, annotation and translation), Queens’ Old Library contains many remarkable examples of marginalia. Ranging from the scholarly (annotations, mnemonic devises, manicules) to the distinctly recreational (crude poems written on the flyleaves of Bibles, personal notes and doodles), these lines and markings offer an insight into the daily practices of book use.

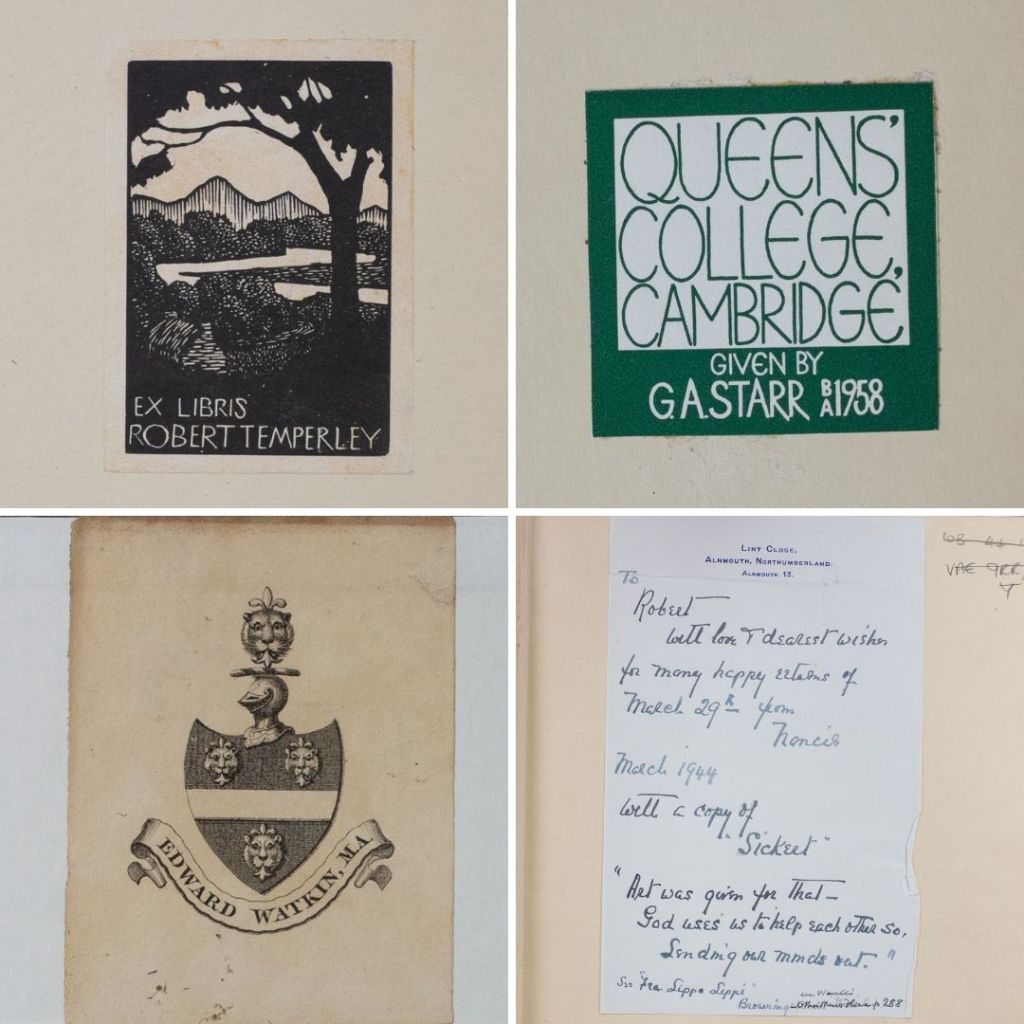

In addition, the Library collection is known for its many original calfskin bindings. As well as offering us indications of the books’ provenance and the relationships between past owners, as in the case of William Cecil’s books given to the President of Queens’, or the library shared by two theologically opposed Cambridge preachers, the bindings illustrate the craft and skill of sixteenth-century bookbinders. Looking at the books that we hoped would feature in the exhibition, we found that they were united by these themes of daily use and personalisation.

A quotation, hand-written in a sixteenth-century dictionary, captured this topic perfectly. “Nulla dies sine linea” (not a day without a line) is a maxim that was coined by Pliny to describe the work ethic of Apelles, a Greek painter. Down the centuries, it has been used by many notable authors; Desiderius Erasmus, the celebrated humanist scholar and the subject of one of our exhibitions, used it in its negative form, which translated as “today has been a day without a line”, and Émile Zola adopted it as his personal motto and wrote it on the wall above his fireplace. Written in its extended form, “Nulla dies abeat quin linea ducta supersit” (let no day go by without a line drawn to show for it), this quotation, presumably adopted as a motto by the book’s owner, perfectly illustrates the daily craft of book production and use in the early modern period.

What does the exhibition reveal about Queens’ Old Library during the Renaissance?

Firstly, it reaffirms the importance of active reading to the humanist scholars of the Renaissance period. Elizabethan poet Geoffrey Whitney stated that “the use, not the reading of books makes us wise”; in this spirit readers like Thomas Smith, Elizabethan statesman and Fellow of Queens’ and the subject of our penultimate exhibition, used their books thoroughly, and sometimes filled them with annotations, doodles and amendments. The scholarly annotations that feature in this exhibition demonstrate the same attitude towards the use and purpose of books.

Secondly, these additions and redactions, the insertion of replacement leaves, repairs to pages and even the retention of the original bindings all demonstrate that the purpose of the Library was primarily functional. Although books were expensive and precious, they were used repeatedly. These signs of use speak of the way in which books were viewed and used here during the Renaissance.

Not a Day Without a Line: Past lives of Renaissance books in Queens’ Library was curated by Tim Eggington, Lucille Munoz and Hannah Smith. An online version of the exhibition will become available soon on our website.

We are grateful for the support of the Heritage Lottery Fund, whose sponsorship made it possible to appoint a Project Associate to catalogue and promote our sixteenth-century collections.

Leave a comment