Designers are mourning the passing of Wim Crouwel, the celebrated Dutch graphic designer who, in word and deed, championed the idea that creating clear, straightforward communications is the profession’s highest purpose. Crouwel’s family confirmed to ANP that he died in his home in Amsterdam on Sept 19. He was 90 years old.

By many accounts, Crouwel was among the most influential graphic designer in the Netherlands, a place with a storied tradition in graphic arts and typography. He designed phone books, postage stamps, posters, fonts, furniture, logos, and signage systems for state agencies and cultural institutions. Enamored by the pleasing efficiency of Swiss typography and modern architecture, Crouwel embraced a rational, analytical approach in his work. “I’ve always thought a designer should have a cool and detached approach,” he said in a 2012 interview. “I thought that would be of more use to humanity than a personal, expressionist kind of design.”

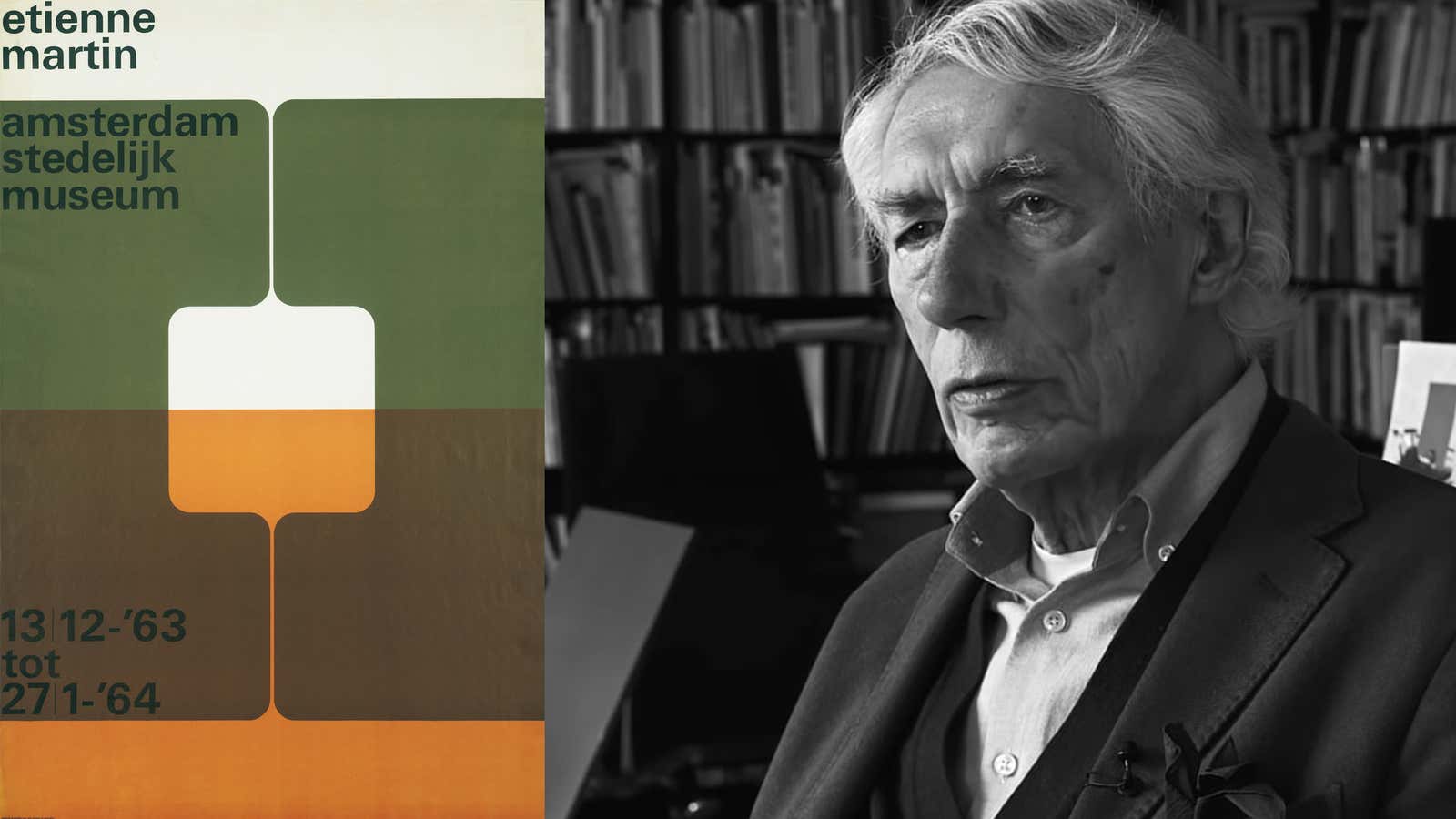

Crouwel proved that a rational approach doesn’t have to be boring. In the 400 striking posters and 300 exhibition catalogs he created for Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam over the course of 22 years, for instance, he demonstrated how variety and poetry can be achieved using a single grid and typeface.”I always had to keep my wits about me to create excitement within the grid,” he explained in an interview with design critic Max Bruinsma. “I sometimes compare it to the lines on a football pitch or any other playing field. Within those lines, you have to play great football and be able to improvise.”

Crouwel began every assignment with a matrix of lines, a tendency that earned him nicknames “Mr. Gridnik” or “The King of Systems.” He held that that arranging design elements along grids created clarity and order for the reader. “I’m a straightener,” he explained. “I like to put everything that’s on the table straight. When I see something that’s lopsided, I put it straight. That’s a nasty habit of mine, but it’s something I’ll have to live with.”

As a professor at the Delft University of Technology and the Erasmus University in Rotterdam, Crouwel taught generations of designers about the virtue of functionalism, a doctrine that prioritizes practicality over artistic ornamentation. This position was radical in the 1960s and 1970s, a time when many graphic designers felt that they had more in common with fine artists.

A genial, elegant man who loved English-style made-to-measure suits, Crouwel roused the Dutch design industry when he agreed to a no-holds-barred debate with his philosophical opponent, Jan van Toorn. Schooled in arts and crafts, Van Toorn believed in putting his personality and personal politics in his work. “In fine art, experiments have been done for centuries…perhaps we should pick up more from that tradition and use more from it,” he suggested. To this Crouwel countered, “As a designer, I must never stand between the message and its recipient.” Their exhilarating duel—pitting rationality against personal expression, the artist versus engineer—remains an inflection point in graphic-design history and became the subject of the 2015 book, The Debate The Legendary Contest of Two Giants of Graphic Design

Beyond the printed page, Crouwel was interested in how his brand of lively functionalism could manifest in other forms. In 1956, he opened an office with Dutch-Indonesian interior designer Kho Liang Ie and designed exhibitions, products and home furniture. Learning about the business model of the design consultancy Pentagram during a UK visit, Crouwel later formed Total Design with industrial designer Friso Kramer, graphic designer Benno Wissing, entrepreneur siblings Paul and Dick Schwarz, and copywriter Ben Bos. Total Design was Holland’s first multi-disciplinary design studio. They worked with clients such as the Schipol Airport, the Dutch Post Office PTT, and the recruitment agency Randstand. They worked on the Dutch Pavilion for the 1970 world’s fair held in Osaka, Japan.

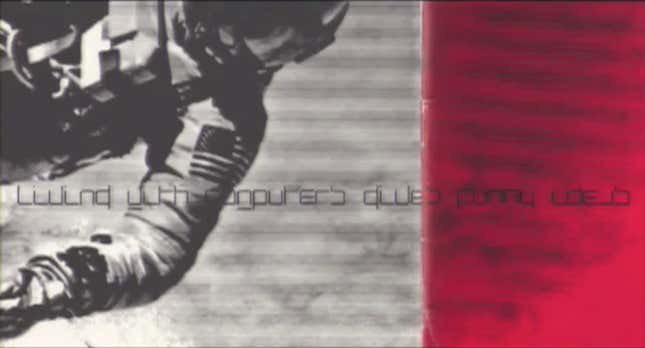

Crouwel was fascinated with digital technology, and how systems thinking shaped graphic communications. In 1967, he even developed a radical typeface to compensate for the crappy display results from cathode ray tube technology used in display screens at the time. The so-called “New Alphabet,” was more of a provocation than an actual proposal, he explained. On a specimen booklet for New Alphabet, Crouwel wrote “living with computers gives funny ideas.”

“Until recently, there would be no major exhibition opening which he would not attend. He was generous with time, engaging with friends and strangers,” says Peter Biľak, a graphic and typeface designer who admired the clarity and simplicity in Crouwel’s work. “He remained rigorous and curious about the new design developments until his last days. I visited him some time ago, and recorded our conversation on a digital recorder. Wim, in his late 80s, was extremely curious about that gadget, and the role of technology in general. We ended up talking about SSD hard disks,” he tells Quartz.

Biľak says that Crouwel’s influence was on his mind when the Royal Dutch Post asked him to come up with a new design for standard postage stamps in 2003. “It was Wim Crouwel’s work which was the benchmark for me personally, as well as for the client, as it was replacing his series of stamps that stayed on the market for three decades. Although, many argue it is impossible, his work was closest to what people call ‘timeless design.’”

Crouwel was diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease several years ago, but the lively design scene in Amsterdam buoyed his spirits.

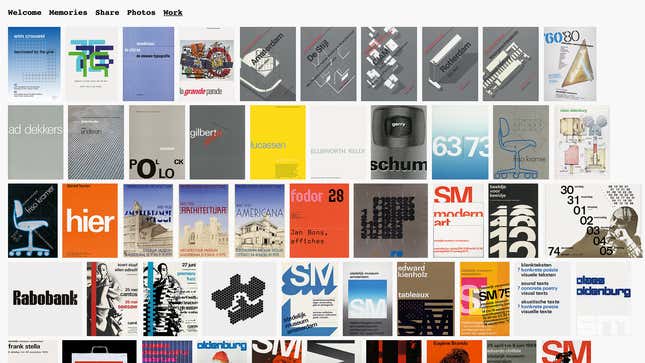

He was a member of the elite Alliance Graphique Internationale and won many prestigious accolades throughout his career. In July, the New York-based Type Director’s Club gave Crouwel its highest medal. He passed away days before the opening of the newest exhibition honoring his legacy. Wim Crouwel: Mr. Gridnik opens at the Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam on Sept. 28, and will run through March 22, 2020. The museum has organized a memorial website where anyone is invited to write a remembrance or post a photo of the beloved Dutch master.