In her now-famous pan of Raiders of the Lost Ark, Pauline Kael excoriated Steven Spielberg and George Lucas for wasting their talents on a film that aspired to be a B movie. “Spielberg—a master showman—can stage a movie cliché so that it has Fred Astaire’s choreographic snap to it,” Kael said. She had his number: The film (and the pair’s three sequels) is a sort of kitchen-sink pastiche, not of a single style of filmmaking but of everything the moviemakers loved from their own childhoods—Carl Barks comics, Citizen Kane, Gunga Din, Lawrence of Arabia, Stagecoach, Lost Horizon (the remake of which it actually raided for footage), and the cheap adventure serials that the two men had seen as children. That struck Kael, who also loved the artistic heights to which movies could aspire, as an unpardonable liberty to take with the audience.

She had the audience wrong, though—at least the part of the audience that was the age of the filmmakers. “The moviemaking team appears to have forgotten the basic thing about cliff-hangers: we had a week to mull over how the hero was going to be saved from the trap he’d got himself into,” she sniffed. Nope: Studios like Republic released serials weekly in the 1930s and ’40s in an effort to keep moviegoers returning regularly, but by the time the Indiana Jones team was soaking up stories of spacemen and lost treasure in the ’50s, those serials had migrated to television. In one story conference, Lucas said he wanted Raiders to have some kind of death-defying moment every 10 to 20 minutes, more or less mimicking the experience of watching several installments of Buck Rogers or Flash Gordon uninterrupted, since that was how they aired on TV in the ’50s. Young people were used to drinking in set piece after set piece, and two technically brilliant filmmakers with enough money to make a feature were happy to crank up the energy way past the tolerance of their elders.

I can personally attest to the queasy pleasures of the serial experience. When I was a kid, my dad, anxious, like all dads, to introduce his offspring to artifacts of his own childhood (which, in his case, was roughly contemporaneous with Spielberg’s), scored an unexpurgated copy of Flash Gordon Conquers the Universe on two VHS cassettes. I loved them. In fact, I found them hard to stop watching even after far too long in front of the television, and at least once I managed to creep downstairs to the VCR on a Saturday morning when most of the house was asleep and binge the entire thing in a single face-melting four-hour sitting. (Feel free to do this yourself if you want.) Raiders is probably my favorite movie, not least because it’s the skeleton key to so many other films that inspired its two colossal auteurs, and perhaps that is why it is so uncomfortable to hear echoes of Kael’s dismissal in my own distaste for Indiana Jones and the Dial of Destiny, allegedly Harrison Ford’s final adventure as the whip-cracking tomb raider.

For the original film, Lucas and Spielberg gleefully pilfered stories of adventure from foreign civilizations, the basic atomic unit of American pop culture during their formative years in the ’50s. Hiram Bingham had “discovered” Machu Picchu in 1911; in 1954 Barks had replaced him with Scrooge McDuck, and Hollywood had made him into a louche jerk named Harry Steele (Charlton Heston) in Secret of the Incas. The Raiders team stole their hero’s wardrobe from Secret—costume designer Deborah Nadoolman said the crew watched the film together several times—and the boulder sequence from Uncle Scrooge. When Indy channels a shaft of sunlight that reveals the location of the movie’s sacred MacGuffin, a scene lifted from Secret of the Incas, he’s dressed in a near-exact copy of T.E. Lawrence’s Bedouin garb in Lawrence of Arabia. It’s a slightly embarrassing quote—not as embarrassing as Shia LaBeouf’s Mutt Williams appearing in costume as Marlon Brando in Kingdom of the Crystal Skull—but perhaps it’s a little charming even so, not unlike catching a kid trying to wear his dad’s suit.

Spielberg and Lucas were also vigilant stewards of popular culture, not just appropriators of it. Star Wars may have looted Akira Kurosawa’s Hidden Fortress, and Indy may be an amalgam of Toshiro Mifune characters, but Lucas paid that debt back in literal dollars, forcing Fox to finance Kurosawa’s Kagemusha as a condition of distributing The Empire Strikes Back. Both he and Spielberg worked to make the Japanese auteur’s final film, Dreams, a reality. A long-overdue restoration of Lawrence of Arabia had stalled out; Spielberg and Martin Scorsese (who plays Vincent van Gogh in Dreams, incidentally) got it rolling again.

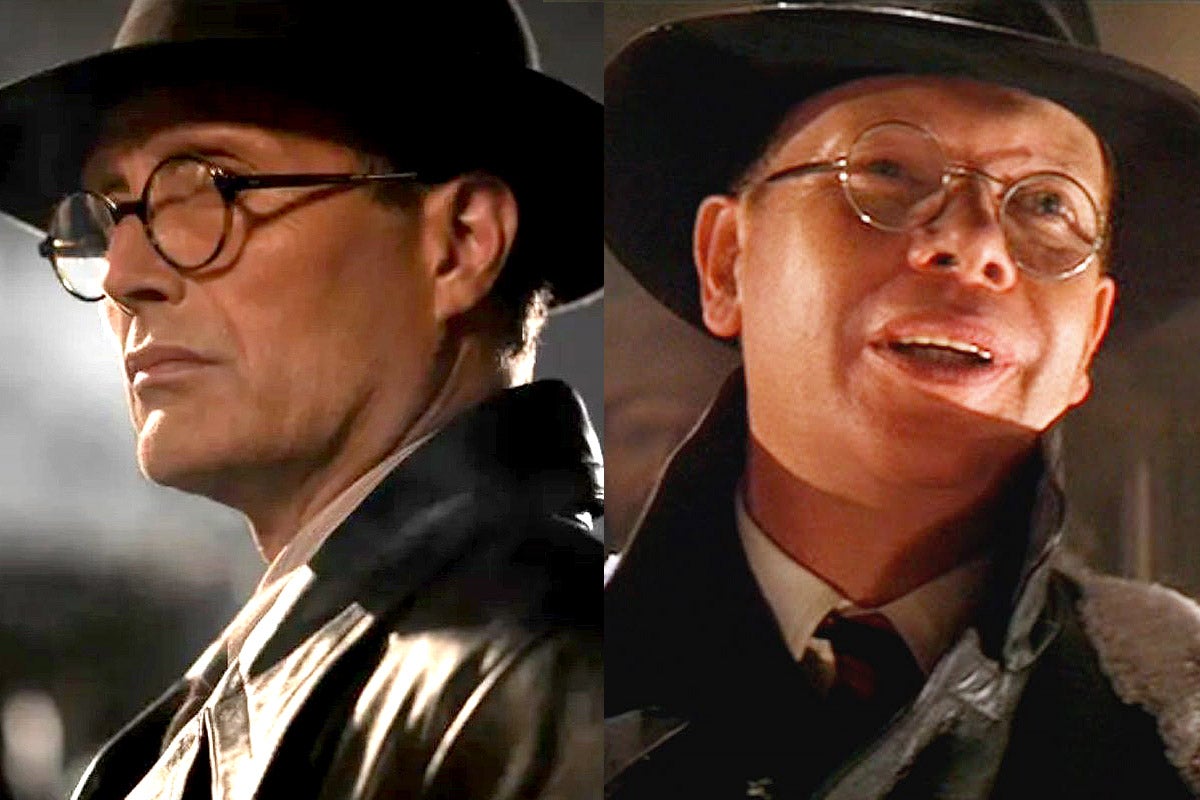

But watching Dial of Destiny, it’s hard not to think that Indy’s world was a lot bigger in 1981. We more or less have the Republic serial model back again in the form of the Marvel movies and TV shows, which deploy every few weeks and draw liberally on the chase-scenes-and-quips model perfected in Raiders and strung out enjoyably across Temple of Doom and Last Crusade and even parts of Kingdom of the Crystal Skull. During Dial of Destiny, we no longer see references to movies made before Star Wars; instead, the new film, directed and co-written by James Mangold, is an homage to the other Indiana Jones flicks, with Mads Mikkelsen’s baddie at one point jacking his whole outfit from Raiders’ Arnold Toht and, at another, donning René Belloq’s white suit and fedora. John Rhys-Davies reprises not just his role as Indy’s faithful counselor Sallah but the few bars of H.M.S. Pinafore he bellows at the end of the original film. Indy and Marion Ravenwood (Karen Allen), on the outs at the beginning of Dial, reenact Raiders’ “Where does it hurt?” scene right before the camera discreetly gives them some privacy as the film ends. And that scene in which a sunbeam reveals the location of the titular relic is back, except this time to nod to Raiders rather than to shine a light on a forgotten Charlton Heston vehicle.

These Easter eggs can be tough to swallow if you really remember Raiders with any admiration. Though he softened over the years, Ford’s Indiana Jones began cinematic life as an almost irredeemable monster; that’s the whole point of Belloq, a dashing fascist fashion plate who tends to saunter off with the treasure Indy bleeds for. “It would take only a nudge to make you like me—to push you out of the light,” Belloq teases. Indy’s love interest, Allen’s indomitable Marion, is proof of Belloq’s observation—Indy took advantage of her when she was “a child,” she says (15, if you do the math). What makes Marion’s get-well kisses so sweet is that they don’t actually come to anything. Indy falls asleep—he’s overmatched, just as he always is, beginning in the very first sequence, when he nearly gets himself squashed by a boulder and loses the treasure into the bargain.

Nerds have debated whether or not Dr. Jones actually accomplishes anything over the course of the film, cosmically speaking—the ark of the covenant turns out to be perfectly capable of defending itself after he fails to do so—but the movie’s most important stakes have to do with the disposition of its hero’s soul, not the wrath of God. Ford is blindingly handsome and as charming as one of Indy’s hated snakes, but can a morally compromised predator become someone genuinely worth loving?

It’s a much more interesting question than anything in Dial of Destiny, which declares itself to be thematically interested in whether history and the people who love it matter anymore. The text of the film answers the question in the affirmative, but everything else about it says “not if we can help it.” In the Disney galaxy of intellectual property, the Indiana Jones franchise is one of the smaller constellations, and its affection for films of a bygone era is its least marketable quirk.

Things have changed, largely because of Lucas and Spielberg. The films they fought to see recognized as great works of art now not merely have become canon but have aged into snootiness; whether or not it inspired the terrific truck chase in Raiders, Stagecoach is generally the purview of film buffs, now a tweedier demographic than the kind of nerd who dreamed up Indiana Jones. Same with Lawrence of Arabia, Lost Horizon, and the rest. Instead, everything looks like a Spielberg movie, even when it’s not. Our world is now filled with Apple products that look like set dressing from Minority Report, and moviemakers like J.J. Abrams have constructed entire visual styles out of E.T. The most popular show on the most popular streaming service is a travesty of Spielberg’s work in every sense of the word. We have more, but we draw on far, far less.

Raiders was conceived as a sumptuous meal of elegantly plated junk food, prepared in the firm belief that it’s actually not as bad for you as its detractors have declared. “In addition to the artistic pleasure given by comic stories and drawings such as Carl Barks’, comic art has something to say about the culture that produces it,” Lucas wrote in his introduction to a collection of the Barks stories that had so inspired him. And so it was, he and Spielberg believed, with children’s television and corny Westerns. The old serials were produced with a large measure of cynicism—some sequences of Flash Gordon are just footage from other films, notably the German mountaineering adventure movie The White Hell of Pitz Palu (starring Leni Riefenstahl!). But Lucas and Spielberg have forcefully and successfully made the case that low-cultural art is hugely valuable artistically and monetarily, and that case wasn’t generally accepted when Flash Gordon was being produced.

Now the companies that generate mass entertainment seem concerned primarily with wresting away the rights of artists and forcing every narrative angle to rebound back into intellectual property that they control directly. Stories must form part of a big collective mosaic of trademarked distinctive likenesses, deepening characters and complicating their stories only when those characters can be repurposed for another iteration. The opening sequence of Dial of Destiny, in which Ford is computer-graphically de-aged back to 1981, reads almost as a threat: “Like this?” it seems to say. “There’s more where it came from.” Imagine if Lucas and Spielberg had to dress up Indy as Lawrence not because they loved the David Lean movie but because Hasbro had a line of Lawrence of Arabia action figures coming out. “Essentially, George Lucas is in the toy business,” Kael wrote. She hadn’t seen anything yet.