Untitled (Self-Portrait with Blood)

1973

As a Cuban immigrant woman, I have always felt a sense of displacement. The streets of where I grew up in southern Miami are made up of just that – drifting souls, torn from the motherland and attempting to shift and create a space for ourselves in a country that’s never wanted us. There’s a search for a home that evades us, only made distinguishable by cafecito, international calling cards and the kindness of strangers. My own existence here on this very soil I rarely take for granted. My father stands as the only Cuban to ever receive a visa from the State Department for humanitarian reasons, an act that afforded us a different life. This feeling of an exile I didn’t choose never made any sense, until I was introduced to the work of Ana Mendieta – Anita, as my dad likes to call her. They knew each other the same way that everyone in Havana knows each other, the same way that a neighbor is family. Even then, everyone knew Ana would be remembered.

An artist who used her body as a tool to connect to the four basic elements of nature, Ana’s work has slowly become what I return to when I feel like I am drifting, anchored at sea. One of the first things I discovered about her is one that I haven’t forgotten since – she collected soil from places that were important to her (Cuba, the Nile), as a way to come to terms with the impermanence of her time there. “She called it a charge. An object would have a charge, it would have the vibration of that place,” her sister, Raquelin, explained in an interview with the Huffington Post.

Ana was one of the 14,000 unaccompanied Cuban children who were sent to the United States between the years of 1960 and 1962, in a collaborative effort by the government and Catholic charities, as well as what would eventually be one of the saddest narratives in our history. It was the start of Fidel Castro’s communist regime and, amongst rumors that he was planning to send minors to work camps in the Soviet Union, panic stirred within Cuban families who couldn’t afford to uproot their lives. Detached from everything she knew, Ana and her 14-year-old sister Raquelin arrived to a refugee camp in Dubuque, Iowa and would spend the next two years fighting to stay together since. Though she eventually reunited with her family in 1966, Ana would spend the rest of her life trying to rediscover the home she had lost.

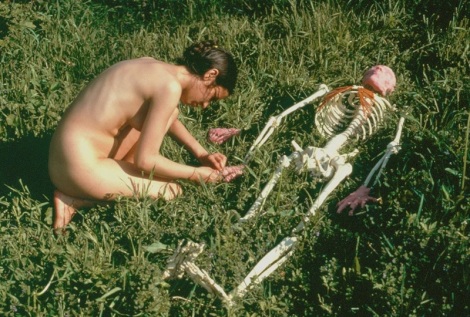

Ana’s vision began to emerge while attending the University of Iowa, studying the avant garde and the nature that surrounded her as well as growing a deep interest in the spiritual practices of santeria. It is this period of time where her focus turned towards blood and violence toward women – when university student Sarah Ann Ottens was raped and murdered on campus, Ana tied herself to a table for two hours, covered in cow’s blood. Students and faculty were invited to stop by as she lay motionless, forcing the audience to grow aware of their own responsibility.

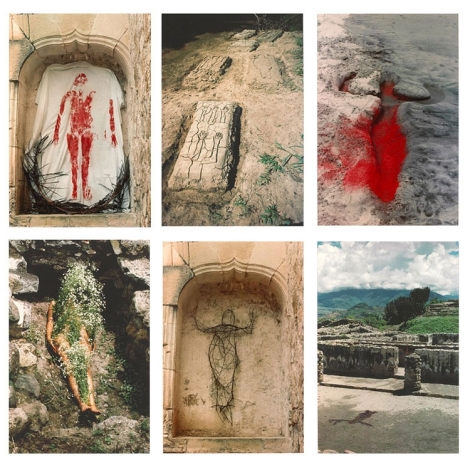

Before long, Ana Mendieta became a name that everyone in the art world pronounced with respect. Her work in Mexico gave birth to the Silueta Series (1973-1980), a range of silhouettes made up of earthly materials that carry both presence and absence, illusion and reality. Her body became a tool to reconnect to the source – the earth where we are born, where we are buried. In a 1981 statement, Ana said: “I have been carrying out a dialogue between the landscape and the female body (based on my own silhouette). I believe this has been a direct result of my having been torn from my homeland (Cuba) during my adolescence. I am overwhelmed by the feeling of having been cast from the womb (nature). My art is the way I re-establish the bonds that unite me to the universe. It is a return to the maternal source.”

Ana Mendieta, Silueta Works in Mexico, 1973–1977

In 1978, Ana joined New York’s Artists in Residence (A.I.R. Gallery), the first established gallery for women in the United States. Growing heavily involved in the maintenance of the space as well as her own work with other women artists, she concluded that “American Feminism as it stands is basically a white middle class movement.” It was here that she met Carl Andre, a minimalist sculptor who later became her husband.

On the morning of September 8, 1985, Ana fell to her death from the window of her 34th floor apartment in Greenwich Village, New York. Andre was in the apartment when neighbors heard violent fighting and cries of “no.” Despite Ana’s acute fear of heights, Andre insisted that she committed an act of suicide and was tried and acquitted in 1988 on grounds of “reasonable doubt.” What hurts the most about Ana’s death is the use of her own work against her – Andre’s lawyers often brought up contents of her highly personal work to prove her mentally unwell and the likeliness of self-harm. The death of Ana is not unlike the losses of brown and black sisters whose lives are never given justice, never announced on the morning news. Andre murdering his own wife had little impact on his career and, in fact, is still considered a critically acclaimed sculptor in Europe. Though her voice was taken from us, her work continues to grow a life of it’s own through activists and artists who see themselves in Ana Mendieta.

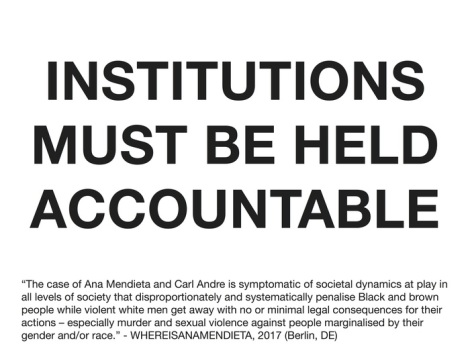

WHERE IS ANA MENDIETA is an activist group founded in London in 2016 by female and non-binary artists who keep Ana’s story alive. With high-profile protests formed at Carl Andre exhibitions at the Tate Modern and Hamburger Bahnof, their defiance not only serves to remind us of the consequences that evade white men, but the recognition they receive despite them. “These are stories created by the dynamics at play in all levels of a society that disproportionately and systematically penalizes black and brown people, that dismisses survivors, that excludes women/non-binary/trans people, while violent white men get away with minimal or no legal consequences for their violent actions,” Berlin-based founding member Naomi Bisley tells Art Slant. “Of course the art world is included in this structure, and every single gallery/institution/individual who participates in it without speaking out is complicit.”

What connects each of us to Ana’s work is not just her haunting vulnerability, but our own mirrored back at us. By viewing pieces like Silueta Series we are invited to draw parallels to our own trauma, the baggage of past lives we carry, rooted in the very nature that surrounds us. As I type this in the comfort of my own apartment (one that I have felt a need to construct and carve out for my own sake, sometimes with the tears and blood shed to be able to have a space on earth that belongs to you and only you, no matter how temporary, very much a shared mentality in New York City), not too far from where Ana herself was murdered 32 years ago, it’s hard for me to not feel the deepest sense of loss, not only shared through the land we came from but the same burning need to decolonize our own bodies. I have referred to Ana here by first name not out of lack of respect, but because I feel like I know her. I have been able to come to terms with missing a home that was never mine, as well as my own existence in this body and this life, all due to Ana Mendieta giving us hers.

The island of Cuba has been ravaged with some of humanity’s darkest moments, it is true – there is no point in time as devastating as the brink of a nuclear war, an evil capable of wiping our existence before we are even aware of it – but it is also the source of unwavering joy, a solace that comes from being in touch with the universal, the simple act of being alive. There is no happier people than the Cuban people. We find light even when there is none – we construct it out of thin air, because it’s all we know. An island that my father hesitates to call home, having had a target set by Castro on his back, but one that I know is still the origin of everything I am and ever could be, created out of a resistance instilled in us since we were born.

The life of Ana Mendieta reaches far beyond her death and deep into a future where we dismantle the white patriarchal structures that have tried to erase and silence us without success. The last line of WHERE IS ANA MENDIETA’s manifesto reads: “A violent white man over a dead woman of color, this is a rhetoric we encounter constantly, daily, and it must end.” We invite you to have a closer look into Ana’s oeuvre, one that encompasses the impact of our body on this earth even after we have left it.

Untitled (Silueta Series), 1973 – 1977

Untitled (Silueta Series), 1973 – 1977

Untitled (Silueta Series), 1973 – 1977

Untitled (Self-Portrait with Blood), 1973

Untitled, 1973 – 1977

Untitled (Silueta Series), 1973 – 1977

Untitled (Glass on Body imprints), 1972

Body Tracks, 1974

Body Tracks, 1974

Blood and Feathers, 1974

Itiba Cahubaba (Esculturas Rupestres), 1981

Cave to Canvas, Silueta Series, 1973-1977

Words by Vanessa.

All images courtesy of the Ana Mendieta estate.

More details of WHERE IS ANA MENDIETA can be found here.