There existed a time, in the early 1990s, when the internet was a far-off thought. The dissemination of information during the early aughts of this decade had taken on varied forms, mostly by word of mouth, flyers, newspapers, and magazines. It took time for ideas to gain traction and it required people to do the hard and dirty work of research to get to the bottom of things. Information required patience. But once in the hands of the masses, information quickly became mainstream.

The emergence of women-led punk rock in the Pacific Northwest during this time gave rise to what is now known as the third wave of feminism. Washington was the charmed state that bred groundbreaking bands like Nirvana, Pearl Jam, Mudhoney, Soundgarden, and Mother Love Bone, pioneers of the grunge and punk rock scene that saturated the radio waves. The darlings of the industry were predominantly male, with little space reserved for their female counterparts. In response to this boys’ club culture, female musicians not-so-quietly started a revolution of their own kind, carving out their own space in the music business if no one was willingly going to give it to them. Bands such as Bikini Kill, Bratmobile, Babes in Toyland, and Heavens to Betsy set out to normalize anger and celebrate their sexuality.[1] Their music began to express their discontent; their dissatisfaction in the industry led to underground meetings to address the sexism they had been experiencing behind-the-scenes; and their writing began to inform their personal and professional voices, their platform, and their activism. Fueled by the lack of validation and their desire to start a “girl riot” against capitalism and the patriarchy, the Riot Grrrl movement was born.[2]

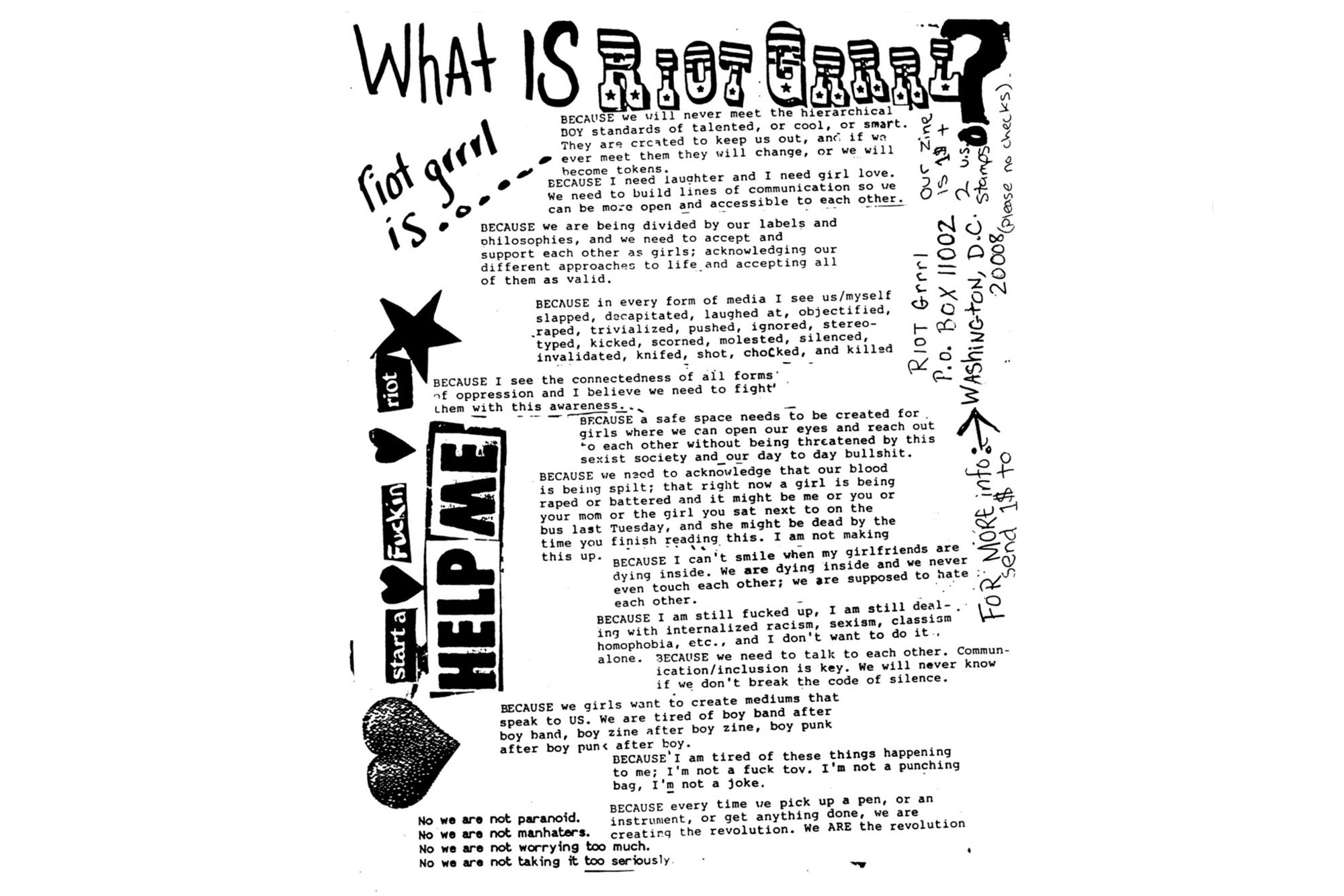

The Riot Grrrl (the three r’s replacing the “i” to reclaim the perceived passivity of “girl” and to add a more appropriately fierce growl [3]) manifesto appeared in the pages of Bikini Kill’s second issue of their underground fanzine. At the time, fanzines were a means of communication between die-hard fans and the artist–it was the paper version of Instagram and Twitter. Here, Bikini Kill began to articulate their thoughts and experiences as women in society, how they felt like second-class citizens: defeated, invisible, ignored, and dismissed. Their fans, mostly young women, connected to the content, felt seen in their struggle, and carried on the battle cry. Over the years, this manifesto was circulated, copied, and distributed to the masses, ad infinitum. The fact that only two issues of this fanzine were ever created (the first issue can be perused here) points to the incredible convergence of timely material, cultural significance and relevance, and the demand for social change. The manifesto and the movement shone a light on gender inequality and gained heightened momentum during the 1990s, expanding from proud proclamations to initiatives created to make touring and concert venues safer for women who were working, performing, or attending.[1] The oft-repeated phrase, “Girls to the front!” was first shouted by Bikini Kill’s frontwoman Kathleen Hanna during a concert, encouraging women to make their way to the front of the crowds, both physically and metaphorically. “Girl Power” was also the name of the second issue of Bikini Kill’s fanzine, which was made even more popular during the height of the Spice Girls’ reign in pop music in the late 1990s.[2] What was once a covert subculture quickly grew into a feminist outcry that is still relevant today.

Thirty years later, we would be hard pressed to say that we have made relevant strides toward gender inequality. Everything that was stated in the Riot Grrrl manifesto still holds true; everything that our sisterhood has fought for, we are still fighting for today. How many more years will it take to get there? How many more waves of feminist movements before we’re afforded space at the front, without having to demand it? The revolutionary spirit is still inside us. And there’s still so much more work to be done.

[1] Hunt, E. (2019, August 27). A brief history of Riot Grrrl – the space-reclaiming 90s punk movement. NME. https://www.nme.com/blogs/nme-blogs/brief-history-riot-grrrl-space-reclaiming-90s-punk-movement-2542166

[2] Feliciano, S. (2013, June 19). The Riot Grrrl Movement. New York Public Library. https://www.nypl.org/blog/2013/06/19/riot-grrrl-movement

[3] Rosenberg, J. and Garofalo, G. (1998). Riot Grrrl: Revolutions from Within. JSTOR. www.jstor.org/stable/3175311