It’s no secret that trends that start underground end up flowing into the mainstream at one point or another. What is surprising, however, is how quickly stylistic changes seem to be made nowadays. In the age of COVID quarantines and tunnel-visioned TikTok “For You” pages, the Riot Grrrl punk subgenre is seeing a massive boom amongst Gen Z.

Many women are growing out of their “I hate all things feminine” phases and are embracing femininity, not as a weakness, but as something to harness and be proud of.

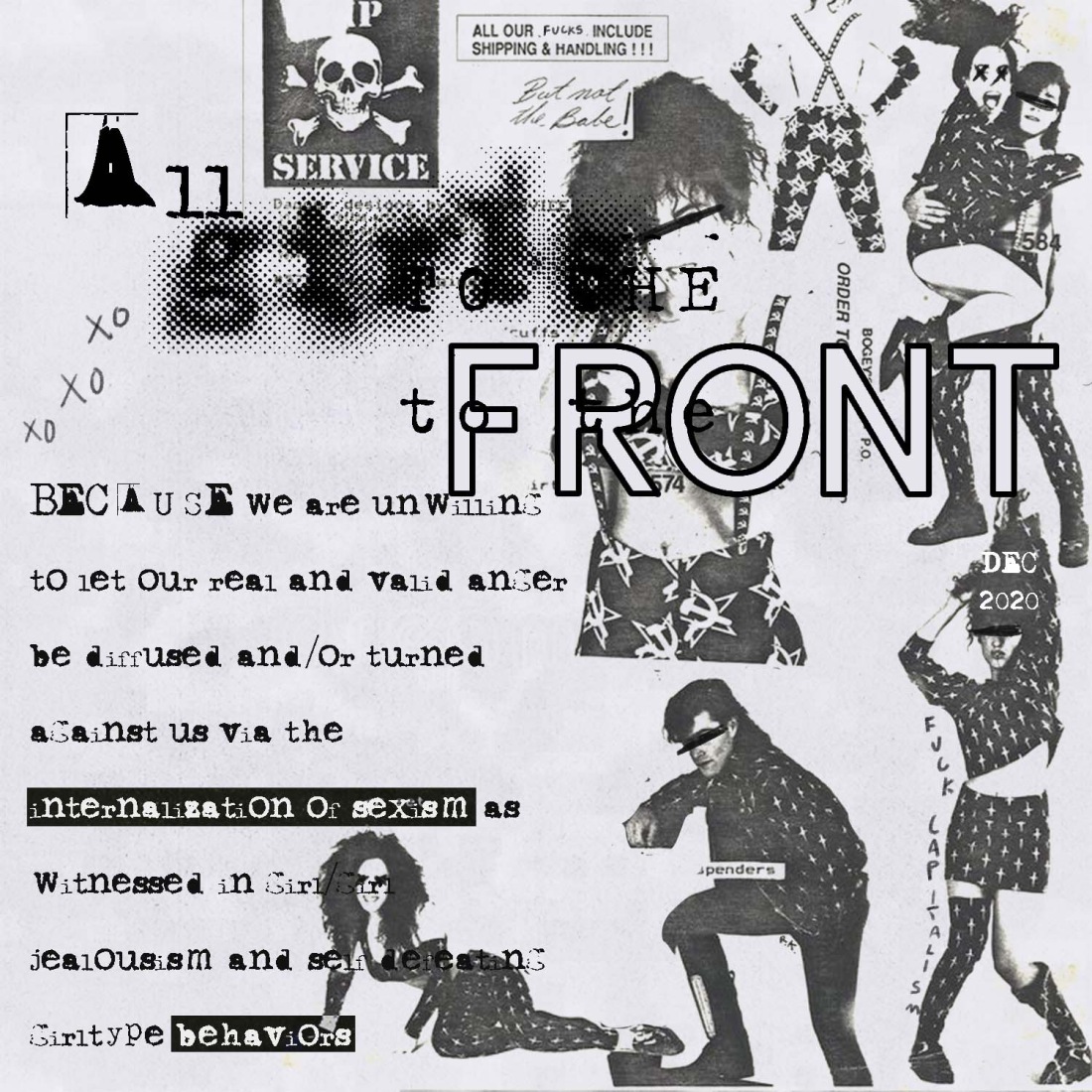

For a bit of context, Riot Grrrl has its roots in Olympia, Washington. The ‘90s punk movement was a safe haven for misfits, but not a welcoming environment for women. As a result, many punk women created fan zines, which were initially popularized by British punks in the ‘70s. Two of the most popular feminist zines of the ‘90s are Bikini Kill by Tobi Vail and Kathleen Hanna and Girl Germs by Allison Wolfe and Molly Neuman.

“I feel completely left out of the realm of everything that is important to me. And I know this is partly because punk rock is for and by boys,” Vail once wrote in Jigsaw, her solo zine prior to joining with Hanna.

Zines were a great way to spread the message that women belonged in punk scenes to other women, but the tougher crowd was not as receptive. To bridge the gap between creating their message and getting it into the minds of the people who needed to hear it, Vail and Hanna formed Bikini Kill, a band named after their zine, with Billy Karren and Kathy Wilcox. Wolfe and Neuman of Girl Germs were joined by Erin Smith to form Bratmobile.

Bikini Kill and Bratmobile were two of the big driving forces in the Riot Grrrl movement in the early ‘90s. They recognized that if you wanted something to come to fruition in a punk scene, your best bet was to communicate it through music. At their shows, performers often called for “all girls to the front,” to encourage participation of women in the crowds at punk shows, where they were often harassed or overlooked.

The second issue of Bikini Kill (the zine, not the band) included the Riot Grrrl Manifesto, and thus the stamp was official. Traits of the Riot Grrrl movement were an emphasis on DIY, the freedom of youth, and wearing feminine dresses, makeup, and hairstyles with a disregard for the male gaze.

BECAUSE we are unwilling to let our real and valid anger be diffused and/or turned against us via the internalization of sexism as witnessed in girl/girl jealousism and self-defeating girltype behaviors

(Bikini Kill, The Riot Grrrl Manifesto).

The initial hit of Riot Grrrl’s popularity faded out by the late ‘90s, but there seems to be a huge resurgence as of mid-2020. Many women are growing out of their “I hate all things feminine” phases and are embracing femininity, not as a weakness, but as something to harness and be proud of. Increased free time due to lockdown sparked a new wave of online and print zines. And finally, the elephant in the room that needs to be addressed… is how the internet influences this whole ordeal.

First and foremost, the aesthetic of Riot Grrrl saw a resurgence along with the influx in DIY culture and the boom of supporting small businesses. Handmade jewelry and clothing became a staple for people who existed in primarily alternative crowds, and the camaraderie of supporting the passions of small artists naturally lends itself to everything Riot Grrrl stands for. This, in combination with the rise of “e-girls” created something along the lines of a modern Riot Grrrl.

While that’s all fine and dandy, when it comes to Riot Grrrl, I encourage you to learn about the real meat and potatoes of the movement—the fact that it was a movement, not just an aesthetic.

I honestly think the TikTok algorithm takes a lot of responsibility for this one. While TikTok was once something majorly for younger kids to lip sync and dance to songs, it’s become a hub for finding specific niches that appeal to you. Riot Grrrl music and aesthetics became wildly popular under the umbrella of “Alt TikTok.” Once the physical appearances of Riot Grrrls were emulated in the modern world, the attitude followed suit.

Social media in general has had a massive influence on all things revolving around aesthetics, but it’s easy for aesthetics to stop after visuals. While that’s all fine and dandy, when it comes to Riot Grrrl, I encourage you to learn about the real meat and potatoes of the movement—the fact that it was a movement, not just an aesthetic.

The backbone Riot Grrrl is that all are welcome, and it’s important to create space for all Riot Grrrls, not just thin, white, and conventionally attractive ones. As Riot Grrrl resurfaces and gains popularity in the mainstream, keep Vail’s words in mind. Let people into the realm of what is important for them, and make sure punk rock is for everyone by everyone. Out of the mouths of babes, “BECAUSE doing/reading/seeing/hearing cool things that validate and challenge us can help us gain the strength and sense of community that we need in order to figure out how bullshit like racism, able-bodieism, ageism, speciesism, classism, thinism, sexism, anti-semitism and heterosexism figures in our own lives” (Bikini Kill, The Riot Grrrl Manifesto).

Izzy Pedego is .WAV’s Assistant Zine Editor, she wrote the article. Renee Kao is .WAV’s Creative Director, she created the graphic.