Anorexia: How the eating disorder took the lives of five women

- Published

A mother, an Olympic hopeful, a medical student, a waitress and a writer. What do the lives and deaths of five women tell us about how anorexia is managed and treated?

"A lucky dip". That is coroner Sean Horstead's frank assessment of the system by which many patients with eating disorders are cared for.

He has just heard the last of a series of back-to-back inquests into the deaths of five women: Averil Hart, Emma Brown, Maria Jakes, Amanda Bowles and Madeline Wallace.

All died between 2012 and 2018, and the Cambridgeshire and Peterborough assistant coroner unearthed issues including patient monitoring, inadequate record-keeping and missed opportunities in care.

He said the successful treatment of eating disorders was often "reliant on the goodwill of GPs".

Mr Horstead has written a Prevention of Future Deaths report in respect of all five women. He states his concerns about the monitoring of people with eating disorders and calls for greater clinical training in the area, for staff ranging from "consultants to health care assistants".

Cambridgeshire and Peterborough Foundation Trust (CPFT), which runs the eating disorders service all five women used, said it was "committed to supporting further developments regionally and nationally".

Madeline Wallace

Madeline Wallace, known as Maddy, was a bright, motivated 19-year-old who hoped to become a doctor.

Diagnosed with anorexia nervosa in October 2016, Miss Wallace, from Peterborough, "rapidly lost weight" during her first term at Edinburgh University in 2017.

Peterborough GP Dr Rebecca Coates saw her repeatedly during her illness.

Giving evidence, Dr Coates told how at first she had little knowledge of eating disorders, turning to GP colleagues and then Google to research treatment.

Using "best clinical judgement" was incredibly difficult due to the nature of anorexia, said Dr Coates.

Another issue was the "gap" in provision when Miss Wallace went to Edinburgh.

Despite being a "high-risk" patient, Miss Wallace became increasingly concerned about her weight loss there.

Mr Horstead said she only had one dietician meeting in three months, despite raising anxieties surrounding meal preparation and planning.

Ahead of her move to Edinburgh, Dr Penny Hazel, a clinical psychologist at CPFT, tried to get her an appointment at the city's specialist Cullen Centre in April 2017. She was told to call back in August, the inquest heard.

The centre could only accept her as a patient after she had registered with a GP in Edinburgh. An appointment could take a further six weeks.

At the end of 2017 Miss Wallace returned home to focus on getting better.

But on 4 January 2018 she was taken to Peterborough Hospital with chest pains. Feeling "agitated" and worried, she discharged herself.

The next day, during a regular anorexia check-up, she told another GP about her symptoms but was told she had pulled a muscle or broken a rib, her mother Christine Reid said.

On 7 January her mother phoned 111. A nurse from Herts Urgent Care referred her to an out-of-hours GP who made an urgent referral for hospital treatment.

The GP's request was denied and she was sent home with antibiotics.

The urgent care nurse admitted she knew little about anorexia and had not considered sepsis or an urgent hospital admission herself.

On 8 January, Miss Wallace was again taken to hospital and diagnosed with pneumonia which had developed into sepsis.

The following day, doctors attempted a procedure to save her life but she died in theatre.

It is thought her temperature spiked in her final week, but that this was dismissed by a GP as within the normal range for a healthy person.

Her parents believe that because she had a lower-than-normal body temperature, the supposedly normal reading might in fact have been a sign of infection.

In evidence, Dr Coates said assigning eating disorder patients a single doctor might save lives in the future.

Had she seen Miss Wallace in the week before her death, she believes she may have noticed "red flags" - such as her raised temperature.

"I would have noticed a change in Maddy from the previous weeks and looked into it further," she said.

Following the inquest, Mr Horstead said GPs' knowledge of anorexia was "woeful and inadequate".

Emma Brown

Simon Brown said it was almost "indescribable" seeing Emma get sicker and sicker

Emma Brown, 27, was found dead in her flat in Cambourne, near Cambridge, on 22 August 2018.

An accomplished runner with Olympic ambitions, she was first diagnosed with anorexia at 13.

Her mother, Jay Edmunds-Grezio, described how Ms Brown would run 15 miles (24km) a day to maintain her low weight.

She trained with Bedford Harriers under the guidance of Paula Radcliffe's former coach, Alex Stanton, in an effort to boost her self-esteem.

"In her mind she was heading for the Olympics but she couldn't control the amount she was running," said her mother.

Simon Brown told the inquest his daughter's illness was a "descent into hell".

He said: "This is an illness where the patient feared weight gain, she feared recovery, so fought against the help that was being offered."

A post-mortem examination gave Ms Brown's cause of death as lung and heart disease, with anorexia and bulimia nervosa as contributory factors.

Mr Horstead heard how GPs had sent dozens of letters to CPFT outlining concerns, including the lack of time, money and specialist knowledge they had to adequately monitor eating disorder patients.

The coroner voiced concern at the "paucity" of Cambridgeshire and Peterborough Clinical Commissioning Group's investigation into Ms Brown's death.

He noted there were no interviews with her parents or "key clinical figures".

Averil Hart

Averil Hart, 19, of Newton, near Sudbury, Suffolk, loved sports and outdoor activities.

She was, said her mother Miranda Campbell, a "beautiful, intelligent, incredibly witty, fun-loving girl".

First diagnosed with anorexia in 2008, she was voluntarily admitted to the eating disorders unit at Addenbrooke's Hospital, Cambridge, in 2011.

Discharged in August 2012, she moved to Norwich the following month to study creative writing at the University of East Anglia (UEA).

She was admitted to hospital in Norwich on 7 December 2012 after collapsing in her university room, and died at Addenbrooke's on 15 December 2012.

The coroner heard how she had written in her diary about falsifying her weight and restricting her food intake.

On November 13 2012, she wrote: "I can't believe I'm still going, what I'm even running on any more. I just look thin and in pain.

"It makes me so sad."

You might also be interested in:

Locum GP Dr Wendy Clarke admitted she "knew practically nothing" about anorexia prior to treating her, and had to look up guidance for medical monitoring during her first appointment.

The inquest also heard doctors had misunderstood who was responsible for her monitoring, and had not followed up to check necessary tests had been done.

There were delays in her treatment and, over a weekend at the Norfolk and Norwich University Hospital, no specialist dietetic or psychiatric help was sought.

She therefore received no nasogastric-gastric (a tube from the nose to the stomach) feeding, which an expert witness said could have increased her chance of survival.

Mr Horstead found Miss Hart's death "was contributed to by neglect", citing among the factors a "lack of formally commissioned service for medical monitoring of anorexic, high-risk of relapse, patients".

He also said there was a "failure" to speak to Miss Hart's father after he raised concerns about her serious deterioration.

Dr Katie Bramall-Stainer, chief executive of Cambridgeshire Local Medical Committee, told the inquest there was a national failure in treatment and support for "this incredibly vulnerable and fragile cohort of patients who can relapse quickly and relapse seriously, with too often tragic outcomes".

Maria Jakes

Maria Jakes, 24, from Peterborough, died of multiple organ failure in September 2018.

Mr Horstead cited insufficient record-keeping and a failure to notify eating disorder specialists in her final weeks as possible contributory factors.

Ms Jakes, a waitress, had battled anorexia nervosa since the age of 12 and also had a personality disorder.

Because she was sensitive to perceived interference by health professionals - a common trait of people with eating disorders - she was allowed to report her own weight to doctors, despite being known to inflate it.

The inquest heard she was discharged from an eating disorders ward at Addenbrooke's in January 2018, but there was "insufficient monitoring" of her weight before her admission to Peterborough City Hospital in July.

Amanda Bowles

Amanda Bowles, however, was keen to have regular check-ups, repeatedly asking for medical monitoring from her GP.

Her requests, the inquest heard, went ignored for six months after she was discharged from the CPFT's Adult Eating Disorder Service (AEDS) in December 2016, despite her "critically low" body-mass index (BMI).

Her condition went unmonitored until May 2017 when a doctor noted Ms Bowles "hadn't been reviewed for some time, seems to have fallen through the net".

Aged 45, the mother-of-one was found dead at her Cambridge home in September 2017.

Mr Horstead concluded a lack of monitoring likely contributed to her death.

After the inquest, her sister Rachel Waller said "the most important thing to [her sister] was her son".

She said: "She really battled this illness and even though it wasn't her, it was a massive part of her life, but she battled that to enable him to have a relatively normal life."

Beds 'always full'

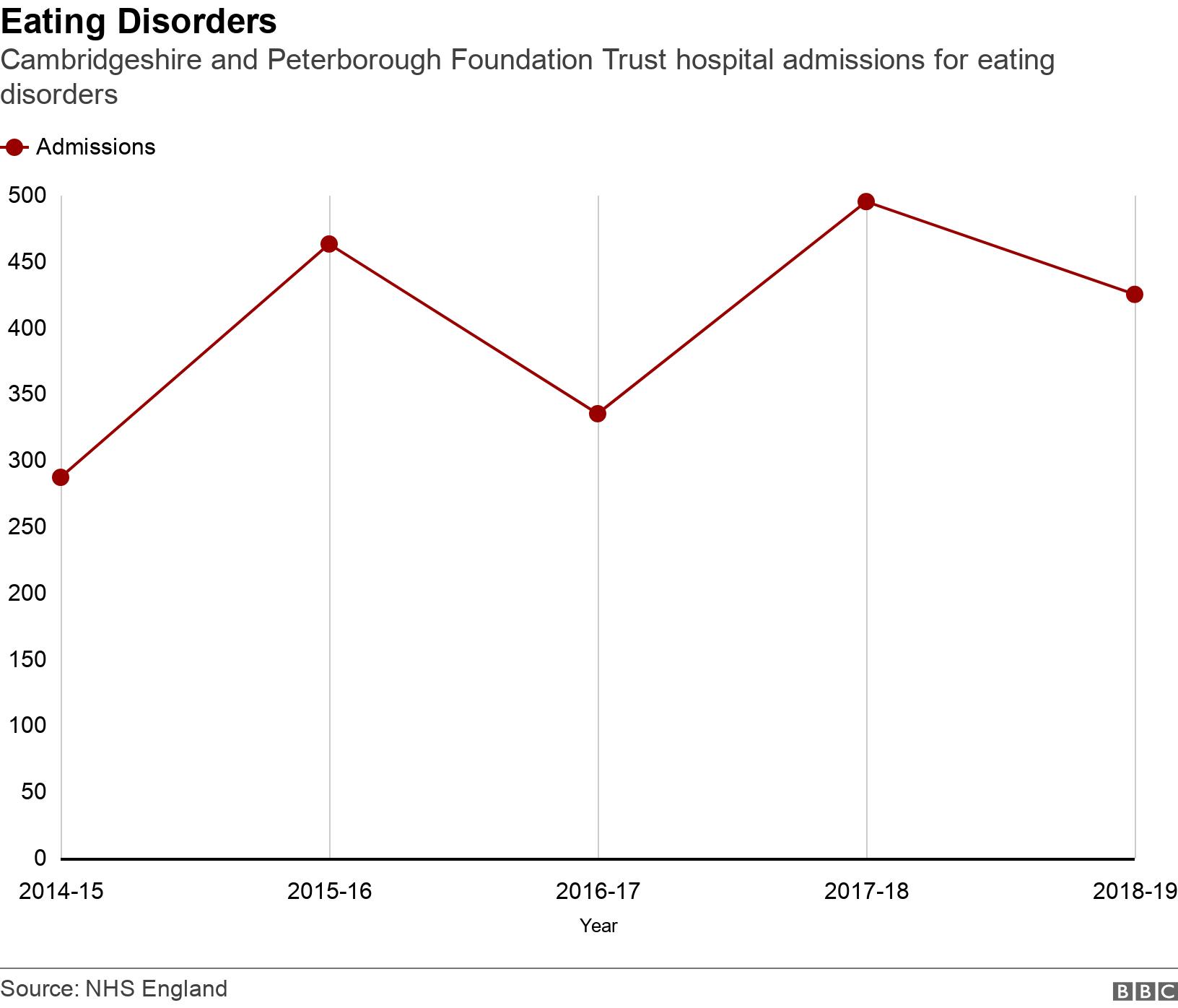

The demand for CPFT's eating disorders service is high.

In 2018-2019, the service received 32 urgent and 533 non-urgent referrals.

The East of England has just 14 inpatient NHS beds specifically for eating disorders. A further 22 private beds can be commissioned.

During the inquests, Dr Jaco Serfontein, clinical director at the trust, said beds were always full.

The families' response

While not officially linking the deaths, saying "each woman was a different person and each had different factors", the coroner found common themes, in particular the "continuing absence" of a formally commissioned provision for monitoring.

This absence, said Mr Horstead, had led to a "miscommunication" between those treating patients with anorexia.

Miss Hart's father Nic, who attended some of the other inquests as well as his daughter's, said the hearings had shown there was "very little monitoring of young people with eating disorders in the community".

"We desperately need better monitoring by the GPs and the eating disorder specialists to make sure there's early intervention," he said.

"We then need the NHS to roll out safe care for people with eating disorders throughout the UK.

"At the moment it's a huge postcode lottery and I think depending on where you live depends on the type of care you will receive."

A lack of beds was raised by Chris Reid, Madeline Wallace's mother.

"Conversations were had about going to a specialist ED (eating disorders) hospital, but she stayed home as there were no spaces locally," she said.

"Her health went downhill rapidly and she spent two days in critical care, and she was then found an emergency bed in the local eating disorder hospital in February 2017."

She also talked of the problems of caring for a loved one with an eating disorder.

"I was very concerned, as was she, but didn't know much about the illness and, as parents, we appeared to have little impact on encouraging Maddy to eat. Excuses were made and she became evasive," she said.

"Typical issues encountered included not appreciating anorexia is a serious/life-threatening mental illness; not knowing about the distorting effect it can have on physical test results and the significance of this for care."

The families of some of the women voiced concern at the lack of funding and education for eating disorders.

Simon Brown, Emma Brown's father, bears no grudge and has nothing but admiration for the clinicians involved in his daughter's care, even inviting some to her funeral.

"I don't know where they find the drive, the skill, to keep going back," he said.

"You're not that well supported, you're under-staffed, under-budgeted, the patients hate you, the parents blame you, there's not enough money and actually we don't yet really know how to treat these people anyway.

"Why would anybody do that?

"Who am I to find blame in the people that have devoted their professional lives to trying to help people like Emma?"

Rachel Waller, sister of Mandy Bowles, fears the stigma associated with anorexia makes it difficult for patients to be treated seriously beyond those who specialise in it.

"This disease has the highest death rate of any mental health condition, and yet it's treated as some sort of adolescent teenage frippery disease where they're simply choosing not to eat because they want to look slimmer," she said.

Maria Jakes' grandmother Kath Wakerly said GPs focused too much on patients' weight as an indicator of illness.

"It seemed... they had to get to a low weight before they were actually admitted to hospital," she said.

"We just need a whole rethink, training across the board: the nurses, doctors, GPs, dieticians.

"I think something good needs to come out of what's happened to these lovely young people. I wouldn't wish that illness on anyone."

A CPFT board meeting in September was told there remained a "gap in provision" for medical monitoring of eating disorders patients, including some who were high risk.

The trust are, alongside local GPs and the CCG, developing a commissioned medical monitoring model, which will be piloted in Peterborough, managing patients according to the severity of their illness.

Those deemed medium to high risk would receive monitoring delivered by CPFT specialists, whereas those in the low to medium group would be monitored by health care assistants, supported by CPFT specialists, in primary care settings, such as GP surgeries.

On the final day of Miss Hart's inquest, NHS England announced it would roll out an "early intervention service" across 18 regions, targeted at young people living with an eating disorder for fewer than three years, in a bid to prevent its escalation.

An NHS spokesman said: "The important and deeply concerning findings and learning set out by the coroner must be acted on by all those services involved.

"The NHS will continue to expand and improve access to eating disorder services, including in Cambridgeshire and Peterborough, to strengthen how adult eating disorder services work together."

If you are affected by any of the issues in this story, you can talk in confidence to eating disorders charity Beat by calling its adult helpline on 0808 801 0677 or youth helpline on 0808 801 0711.

Find BBC News: East of England on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. If you have a story suggestion email eastofenglandnews@bbc.co.uk

- Published6 November 2020

- Published18 September 2020

- Published13 November 2019

- Published8 December 2017

- Published10 January 2020

- Published24 February 2020

- Published23 January 2020

- Published18 December 2019