Andre Agassi is shaved down. Almost seven years since his professional exit, the 43-year-old still has the match-fit swagger of the hardened pro.

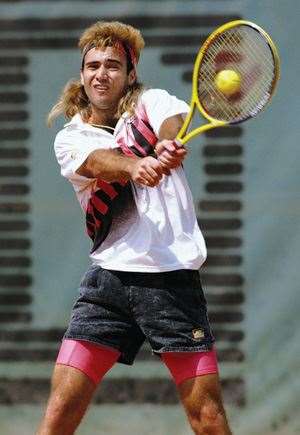

Andre Agassi is shaved down. Almost seven years since his professional exit, the 43-year-old still has the match-fit swagger of the hardened pro. But the security detail outside his hotel room is what you’d expect of a world leader rather than a retired tennis champ. “Elder statesman” is a tag not meant for Agassi ‒ certainly not the angst-ridden, image-obsessed youth in a mullet and “hot lava” bike pants, once derided as “the hardest-working man in show business”. No other tennis champion ‒ or athlete ‒ has so transformed their legacy and public image.

The former wastrel went on to win eight Grand Slams, the first since Rod Laver to collect all four major titles, and outlasted his rivals as the oldest man to rank No.1. He rebounded from an ill-fated marriage to Brooke Shields to win his greatest prize: superstar wife Steffi Graf. And in the wake of the Lance Armstrong sham, Agassi, the ninth-grade dropout, has served up arguably the best-told sporting life story, his jaw-dropping, truth-in-advertising Open. Agassi’s biggest career regret? Not starting his philanthropic work earlier. His competitive instincts these days focus on the goal of expanding the model of his Las Vegas charter school across the US.

It’s only taken us 23 years to have a drink and a chat. I first saw you play in Philadelphia in 1990. You split sets with Pete ...

And defaulted because of ... food poisoning! I tried to get out of my misery in the second set, he won it 7-5. Pete ended up winning that tournament; he beat (Andres) Gomez in the final.

Correct. So it’s true your memory for matches is crystalline. But not for relationships, according to your biographer JR Moehringer.

Yeah well, I had some selective memory issues with my first wife (Brooke Shields) for sure! But that was also a dark time in my life. Part of it was synthetically imposed (laughs). There’s a couple of years where I definitely struggled because I didn’t understand myself, so it was like everything happened around me; a very strong disconnect there. We would laugh about how I remembered everything, and then I would go silent, deer-in-the-headlights, for those two years of my life (marriage to Shields).

That 20-year-old in Philly had a long and crazy ride ahead of him.

(Pause) That’s an understatement.

You did a complete 180 in your career. No other champion has turned around their public image as radically as you did.

Yeah, during their career, for sure. It was a growing up, no question.

Was it a function of your very ambivalent relationship with the game of tennis?

Yeah, it was a deep disconnect, deep resentment, a hatred at times. And that lasted until I was 27 years old. Like there were two different “mes”.

What was the tipping point?

When I gave myself permission to quit. My coach (Brad Gilbert) said, “You’ve gotta start over, or quit.”

This was at the end of 1997, when your ranking sank to No.141 ...

Yeah. And I said, “You know what? I want to quit.” And it occurred to me that in my own rebellious way, I rebelled against myself. I thought, “What if I do this (start over)? I mean, I can’t believe everybody out here likes their life, likes what they do. But they find their reasons. What’s my reason?” And I went out and looked for it. And my reason became my foundation, it became my school. I got out of my way.

When you started out, “entourage” was a dirty word. Now it’s all about “the team”; players hail their teams and give so much credit to the experts around them. There’s been a shift in the culture, a recognition of how important the support team is ...

Yeah, I was ahead of my time in a couple of ways, that being one of them. I needed these people with me, they all served a very distinct purpose. We were all focused on a goal collectively. It was always called an entourage, it was always a negative sort of deal. But it’s nice to see now the sport getting to the point where everybody is getting sophisticated enough, where everybody has their role. That’s only going to improve the game.

Gil Reyes (long-time trainer and surrogate father) and your brother Phillip featured in the latest Open Up film series with Jacob’s Creek. A reading of your autobiography, Open, gives a sense of how much you depended on them.

Yeah, they’re real people. This is a real journey that overlaps all our lives. We all have people in our lives that’ve helped us, shape us, form us. Obviously, writing the book, you work with everybody, you want their memories, but it has to be your perspective. So to hear it from them is really pretty nice. After I’d done speaking engagements for the book, where they were around, I could walk straight through the crowd and the crowd would just gather around them, because they’re the heroes.

Is it even possible today to do it without a support team?

You know, it’s possible for Federer, I guess (laughs). Even he has his wife and that might be all he needs. But for so many years he didn’t have a coach, which was remarkable to me, although he had a physio and a trainer. I don’t think you can do it on your own, no.

Roger’s pink-accented ensemble at the Australian Open made me think of the last time I saw pink on a top male player ...

Hot lava, not pink (laughs).

You can never say to your kids: “You’re going out in that.” They’ll hit you with the hot lava and cerise.

Ha ha. I know, I know.

Are you surprised Roger hasn’t overtaken your four Australian titles?

Umm, ha ha! Roger doesn’t surprise me anymore. What he can do still, he still has time. But he’s at a stage of his career where he has to find ways to win. He’s not the guy people are chasing. But he still can get over the finish line. He still can pull these wins off, but now he has to find ways to do it.

A decade ago, you were the oldest-ever No.1, at age 33. Is that record safe from Roger?

Could he become No.1 again? You can never say never, right? I think that Djokovic and Murray have definitely established themselves as the top two in the world, so it would be a hard climb. Being No.1 is a function of not just getting over the finish line at a tournament, it’s about a lot of wins and I don’t see a lot of wins as being productive for Roger’s goals anymore.

What amazes you most about Federer?

How easy he makes it look. Everybody can say he makes it look easy; I know the game pretty darn well and I can’t believe how easy he makes it look. I watched him at Wimbledon last year

live and was just stunned.

Has Djokovic taken the game to a new physical frontier with his flexibility and freakish powers of recovery?

His defence-to-offence is unbelievable. You never know when the guy’s behind in a point, because it seems like he can hurt you from every part of the court. So in that sense I think he has raised the standard. Federer raised the standard, Nadal trumped him at some point, and I think Djokovic trumped Nadal at some point, as far as raising the standard of the game. }

Andy Murray is now 1-5 in Slam finals. Can he kick on with multiple majors?

He certainly could. I favoured Djokovic (in the Australian Open final) for a couple of reasons, but I did favour Murray to beat him in the final of the US Open and I do favour Murray in a lot of scenarios as I look forward. Youth is on his side and he’s very strong. His legs have got a lot stronger and he certainly believes in his physical capacity.

Was his coach, Ivan Lendl, the final piece of the Grand Slam puzzle for Murray?

People have to connect the dots. If he wasn’t doing it, we’d be saying he wasn’t helping him. I can’t say it’s the reason. Murray does seem to believe in his stamina more. Strategically, he could just be morphing into a player that’s starting to get irritated with being too passive out there. I would imagine Ivan’s helping him, but I don’t know.

Is it more mentoring with Lendl, rather than actual coaching?

I’ve only known Ivan as a dictatorship.

When you return to places where you spent chunks of your career, do the memories come flooding back? What does Australia make you recall?

The preparation. The feeling of just being ready. I landed like a horse that just wanted out of the gate. It’s how Gil (Reyes) always made me feel, it’s how we trained to feel. I felt good physically and mentally, I felt rested and prepared. And going into the arena, memories flood my mind, all the matches ‒ there’s a flood of memories in one moment. The only thing missing was the heat. I wish it was really hot when I got here. That too is a powerful sensory memory. When I would wake up and feel the sun, I knew it was going to be a good day.

Does Paris hold the best memories ‒ a realisation of your dreams on and off the court?

Yeah, I think so. I had a lot of heartbreaks in Paris (losing finals in 1990/91 and getting injured as the in-form No.1 seed in 1995) and I had one of the greatest moments on the court there (completing a career Grand Slam in 1999). And then the irony of me and my wife (Steffi Graf, also French Open champion in 1999) sort of getting over a big finish line there before we really knew each other. I would say a very few great memories made up for a lot of heartbreak in Paris. Seems appropriate, right?

You played in a young and fast era, compared to today. Have the surfaces been slowed down too much? Is the game too gruelling now?

I don’t think it’s too gruelling. I think the athletes are better. It’s gruelling because these guys can get the ball and points are longer, margins are higher. It’s not risky now to rip a ball up the line. It used to actually be a calculated risk, now it’s routine. The intensity of the sport, I think, is a combination of athlete, control, spin, speed ‒ the way these guys move, they can make a fast court look slow. They get to everything.

The average age of a top ten player is much older than in the early ‘90s. Why is that?

The career span of a tennis player has changed because of the sophistication in their training, the realisation they have to put in the hard yards. You know, I was one of the few players that ever lifted weights. When I played, people used to stare at me. Guys are in the gym with bungee cords and I’m putting 300 pounds on a bench press. And the legs now of these guys ‒ the work they must do to have that strength.

The legs look stronger than when you were playing, but not so much the upper body ...

It seems like it, yeah. The stronger I was in the legs, the better I was, for sure, but with my game I needed to be strong in the upper. I played the ball close and I played it early and I needed to be strong. Nowadays, it looks like it’s morphed towards incredibly powerful lower bodies, certain ranges of flexibility and lean, arguably skinny, upper bodies.

You were searingly honest in your book ‒ about taking crystal meth and lying to the ATP, about tanking ‒ and people slammed you for it. Lance Armstrong pedalled a life story full of lies and people fawned over him. What did you make of Armstrong’s downfall? Could a scandal like that befall tennis?

What I thought of that was what everybody thought of it. I thought it was shocking, sickening, hard to stomach, angering. I was one of those who believed him for all those years, ’cause the alternative was unconscionable to me.Do I worry about that in tennis? I don’t know how it’s achievable in tennis. First of all, we’re a sport that has outside governance (of drug-testing), that doesn’t have a horse in the race. Second, it’s a year-round sport and if testing has stayed the same since I was playing, that’s good. Hopefully it’s gotten better, but even if it’s stayed the same, it’s so comprehensive that if we had the sophistication, I’m still not sure how we’d do it.

Tennis players are individuals who are trying to figure it out. A lot of us come from dads who become our coaches, our managers, our nutritionist and trainer, too. So it’s not a team, it’s not a set schedule. So I don’t know how it’d be achievable, but that doesn’t mean we shouldn’t look at how we could made it even more comprehensive, because based on recent events, the sports fan deserves to respect a sport and an athlete who achieves remarkable things, who’s working hard to do it. So I think it’s in the best interest of the fans, the players, the sport, if we constantly pursue measures that can communicate and protect the integrity of it.

You’ve said that your positive test for crystal meth in 1997 played a part in WADA coming into tennis and strengthening drug-testing ...

Because that’s when it changed. It changed the next year. The ATP was in a position it didn’t want to be in, and they realised they shouldn’t be in (the conflict of interest in policing and sanctioning its stars). And so my assumption is that it played a part because it was an ugly time in my life, certainly. Had it been a performance-enhancing situation, they would’ve taken a different approach, I’m sure. But the fact that it was performance-debilitating ‒ it was destroying myself ‒ it seemed a situation they wished they didn’t have their hands in.

Darren Cahill, your friend and coach of five years, said you would make a fine first commissioner of tennis, if such a position was created. Any interest?

Not if there’s a bureaucracy involved, no. If somebody can make decisions ‒ if there’s a position that could lead the sport ‒ I think tennis would benefit from that position.

A benevolent dictatorship ...

Somebody that has the right to have everybody move as a unit, because there’s too many agendas; agents are involved and careers are too short. There’s too many moving parts ‒ like a swamp trying to go everywhere versus a river.

Completing his career grand slam at Roland Garros in 1999 erased painful memories of Paris. Image: Getty Images

Completing his career grand slam at Roland Garros in 1999 erased painful memories of Paris. Image: Getty Images

And you’re too happy doing what you’re doing?

Would I be interested if there was such a position? If I could contribute, I would, because of what the sport’s done for me. This is why I’m with Jacob’s Creek, a way to stay involved in tennis. So yeah, of course I would be interested in helping the sport any way I could.

The great champions ‒ the Everts, Borgs, McEnroes, and now yourself and Steffi ‒ never push their kids to play tennis. Why is that?

Because you’re not delusional about grandeur. If you consider one percent of people in the world achieve a professional status, how many of that one percent gets along in a career without being injured? Call it half a percent. How many of those people have a career good enough and long enough to sustain them for life? Call that a quarter of a percent. That’s all on the foundation of spending one-third of your life not preparing for two-thirds of your life. And now you talk about that one-quarter of a percent, how many of them have you seen end up broke? So call that one-eighth of a percent left. So you’re going to spend your life pushing your child? For what?

The champions know what’s involved, they know it has to come from within ...

And you learn how to define success for yourself as a person, which means how you define success for yourself as a parent. People define success differently.

First-generation Americans (like Agassi’s Iranian-born father, Mike), they came for the American dream. Now we fight not to raise an entitled generation.

Related Articles

Iron Man of Oban to rock RQ

Smith headed home for footy mixed with some work

.jpeg&h=115&w=225&c=1&s=1)

.jpeg&h=115&w=225&c=1&s=1)