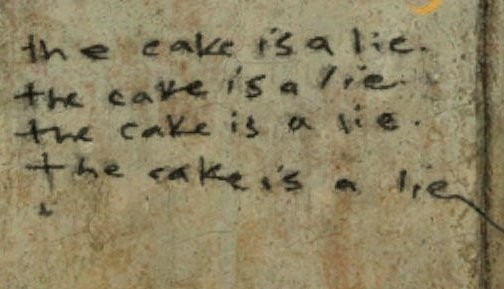

"The Cake is a Lie"

If you don't know where this originates go ask your kids - it's an internet meme. "The cake is a lie" is part of a wonderful and highly original computer game called Portal. The phrase has become one of the many memes that race around the globe such as "Leroy Jenkins" or "Blue Screen of Death".

The "Cake lie" has numerous interpretations from "what you see is not what you get", "don't count your chickens before they hatch" and "your promised reward is merely a fictitious motivator".

I sometimes wonder if e-health or digital health is somewhat like this. For many years we all examined copious reports from esteemed accounting and financial firms who documented in glossy graphics, page after page, the cost-benefits and returns that would come from spending millions, actually billions of dollars and pounds on information technology in health.

Don't misunderstand me though. There are so many benefits from computerized health care that many volumes will be filled describing them. Whole industries, careers, educational programs, learned societies and colleges, legislation, parallel technologies and devices (e.g. CAT and PET Scanners, Gamma Knives, Fitbits, cochlear implants, pacemakers) all rely on health information technology in part or whole for their phenomenal success and unequivocal patient benefits.

But is all as it seems?

Knowledge and information management is not the only aspect of importance in clinical decision making and the health care world is not simply a knowledge industry. It is substantially a social construct with a challenging epistemology and diverse ontologies. Interactions involve negotiation, learning, financing, role and guild politics, leadership, illness behaviour and many other aspects of social reality. Complicating matters further are professional interactions with nursing, allied health, clinical researchers and the constant need to adjust for emerging disruptors such as AIDS or the genomics explosion.

There is great complexity within this cake. The inter-relatedness between decision support interactions between local care delivery units, facilities (hospitals, doctor’s surgeries, nursing homes etc.), the more global clinical informatics space and the totality of the heath care environment. The recipe can expand further into the web of interactions with government, international, pharmaceutical, mental health, and research worlds or shrink down to the micro level of one person interacting with a computer screen with or without a patient present.

Omnipresent are the patients being cared for by this whole socially constructed reality. Have we forgotten how doctors and other clinicians make decisions?

The embracing of Clinical Decision Rules (CDR) and guidelines is not a panacea. McKinlay et al, (2002) demonstrated that clinical decision making can be influenced by simple factors such as age and expertise.

As yet, CDRs have not lead to consistent changes in provider behaviour. The hopes, fears, and mixed record of EBM is rooted in the traditional professional perspective of the clinician as sole decision maker (Timmermans, 2005). Sixty per cent of respondents became acquainted with CDR through informal discussions with colleagues rather than through organized awareness-raising (27%) or educational forums (41%). Guideline endorsement by senior colleagues (68%) and peers (53%) was considered essential to maximizing uptake. Barriers to implementing guideline recommendations were encountered by 62% of clinicians, including insufficient clinical resources (29%) or time (24%), and conflict with accepted practice codes (19%). (Scott et al, 2003). The awareness of CDRs varies from 66 to 15%. There are perceptions of guidelines as being too “cookbook”, “time-consuming”, “cumbersome” and leaving no room for personal experience and judgments, increasing liability risks, with poor patient acceptance. They were not perceived as very helpful by some practitioners (Christakis et al, 1998).

CDRs form only one element of clinical learning. When doctors were asked how they learnt, one researcher stopped counting after reaching a total of 40 different ways (Hawkes, 2013). Many treatment decisions are highly complex and involve more than simply medical knowledge. Patient support, guidance, affirmation, and feedback is important. Time and expense are involved in answering questions and many remain unanswered. Traditionally doctors have sought answers from other doctors or allied health professionals.

Many clinicians value emerging information sources that provide relevant, valid material accessible with minimal effort, confusion and delay. Electronic information tools can meet those requirements especially when portable, fast, easy to use and desirably connected to both a large valid database of medical knowledge and the patient record. Improving Clinical Information Systems (CIS) to implement EBM to reduce clinical error is still my and many others holy grail for health informatics but the issues and the quantum of uncertainties in that decision making is large. We must never become complacent in what we have achieved even if it looks fantastic.

The e-health cake is not a lie but sometimes it can be very alluring and deceptive to clinicians and those seeking greater and greater safety and efficiency.

However, you never quite know what surprises lie within. Everyone loves cake but no one survives on dough alone.

Anyone want a piece of fruit, how about a lovely cup of tea?

----------------------------------------------------------------------------------

References

Christakis, D. A., & Rivara, F. P. (1998). Pediatricians' awareness of and attitudes about four clinical practice guidelines. Pediatrics, 101(5), 825-830.

Hawkes, N. (2013). Educational “events” have only a small part in how doctors learn, conference is told. BMJ, 347

McKinlay, J. B., Lin, T., Freund, K., & Moskowitz, M. (2002). The unexpected influence of physician attributes on clinical decisions: results of an experiment. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 43(1), 92-106.

Scott, I. A., Buckmaster, N. D., & Harvey, K. H. (2003). Clinical practice guidelines: perspectives of clinicians in Queensland public hospitals. Internal Medicine Journal, 33(7), 273-279

Timmermans, S., & Mauck, A. (2005). The promises and pitfalls of evidence-based medicine. Health Affairs, 24(1), 18-28.