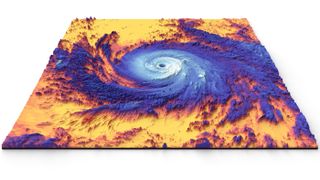

Atlantic's hurricane alley is so hot from El Niño it could send 2024's storm season into overdrive

Unusually high temperatures combined with the abatement of the El Niño southern oscillation could aid the formation of extreme hurricanes this year.

The Atlantic's "hurricane alley" is already experiencing summer temperatures, despite it only being February. And the unprecedented temperatures could be bad news for the upcoming storm season, researchers say.

Since March 2023, average sea surface temperatures around the world have hit record-shattering highs and are still climbing. This ominous ocean heating is being driven by accelerating global warming and the El Niño climate pattern.

"Since the 1980s the world has been experiencing an increased rate of warming. The warming rate is not just simply increasing from year to year though: What we see are phases of faster warming alternating with periods when warming is slower," Joel Hirschi, the associate head of marine systems modeling at the U.K. National Oceanography Centre, told Live Science. "The level of warming we saw in 2023 and now in 2024 is remarkable."

Average sea surface temperatures are now roughly 68.5 degrees Fahrenheit (20.3 degrees Celsius) across the North Atlantic, a full degree higher than the 1981-2011 average. This includes the Atlantic’s hurricane alley, a hurricane-forming belt of water that stretches from the west coast of Africa to Central America.

"Unbelievable: the North Atlantic sea surface temperature is now 4.5 standard deviations above the recent 1991-2020 climatological mean," Brian McNoldy, a senior research associate in marine, atmospheric and earth sciences at the University of Miami, wrote on X, formerly Twitter. "That translates to a 1-in-284,000-year event. Yet here we are watching it unfold, one day at a time. This is deeply troubling."

Related: Big blob of hot water in Pacific may be making El Niño act weirdly

And this increase in sea temperatures could lead to more intense Atlantic hurricanes later in the year, when hurricane season is expected to start on June 1 and end on Nov. 30.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Hurricanes grow from a thin layer of ocean water that is evaporated by winds before rising to form storm clouds. Warmer waters give this system more energy, pushing this process into overdrive and enabling violent storms to rapidly take shape.

Scientists previously found that climate change has made extremely active Atlantic hurricane seasons much more likely than they were in the 1980s. This is because, while hotter oceans don't make hurricanes more frequent, they do make them stronger and faster-growing.

Five storms have blown at an unprecedented 192 mph (309 km/h) or more this decade, leading scientists to propose a new "Category 6" strength to describe them.

However "warm ocean temperatures on their own are not a guarantee for an active season," Hirschi said. "In addition, the vertical wind shear in the subtropics needs to be weak." If the vertical wind shear — the change in wind speed with height — is too intense, the stormy clouds are blown apart and no hurricanes will form.

This is where El Niño could come into play. El Niño is a climate cycle where waters off the tropical eastern Pacific grow warmer than usual, affecting global weather patterns. It is linked with weaker trade winds around the equator, which raises average sea surface temperatures at the equator by at least 2.7 F (1.5 C).

The current El Niño developed quickly in July 2023 and is expected to last until June this year.

During El Niño, winds in the Atlantic are typically stronger and more stable than usual, acting as a brake on hurricane formation. But if the climate cycle follows predictions and dies down or is replaced by La Niña (its cooler counterpart), it could make for an unusually stormy summer.

"The equatorial Pacific is likely to switch to neutral or La Niña conditions during summer and autumn," Hirschi said. "If the anomalously warm Atlantic temperatures persist during that period, we would have all the ingredients for a very active hurricane season."

Ben Turner is a U.K. based staff writer at Live Science. He covers physics and astronomy, among other topics like tech and climate change. He graduated from University College London with a degree in particle physics before training as a journalist. When he's not writing, Ben enjoys reading literature, playing the guitar and embarrassing himself with chess.