As the coronavirus pandemic worsens and the United States now leads the world in confirmed cases, U.S. hospitals are scrambling to obtain protective gear and states and cities are vying for sought-after medical equipment. Many medical professionals and lay people are sounding an alarm about the shortage of masks.

The White House on Thursday suggested that new guidelines would be coming soon advising all Americans in coronavirus hot spots to wear masks or face coverings in public. There is little, if any, clear scientific proof that regular Americans' wearing masks will significantly slow the easily spread respiratory and novel coronavirus associated with COVID-19. But because the pandemic widens with each passing day and there is evidence that asymptomatic virus spreaders may be walking about in public, we may all soon be covering our faces — even if we have to make our own masks out of spare cloth.

We may all soon be covering our faces — even if we have to make our own masks out of spare cloth.

The frenzy over masks reminds me of the 1918-19 influenza pandemic, particularly as it played out in San Francisco, which enacted a mandatory mask law. Most other major American cities ordered standard social distancing regulations like quarantines, school closures and bans on public gathering. San Francisco's law proved less effective, because the city did not also implement robust social distancing measures.

For many Americans during the pandemic, wearing a mask became a symbol of patriotism as we sent doughboys off to fight World War I. Although wearing masks may now give the public a sense of security, I worry that, for the most part, it might convince wearers that they are safe from infection — when they are not. It might also lull wearers into letting down their guard on social distancing and potentially spreading the COVID-19 virus.

The U.S. populace, medical experts now estimate, will put on and dispose of more than 3.5 billion of those flapping mouth and nose guards before the pandemic has ended. Mask manufacturers have told the Department of Health and Human Services that it could take months to meet demand. Many Americans, as their predecessors did during the 1918-19 influenza pandemic, are fashioning their own masks or sewing them in support of hard-pressed medical personnel.

A major problem with most surgical masks, which are made of woven cloth or paper products, is that the force of a wearer's breath against the material can open microscopic holes in the fabric. The longer you wear one, the more microscopic holes. The virus is even smaller than those holes, so it can travel through them — thus transmitting the disease.

For health care professionals, including nurses and doctors on the pandemic front lines, wearing masks is essential. That is because they are exposing themselves to the sick, who cough up a lot of virus. The barrier of a mask at least cuts down on their exposure.

But the scientific data on their effectiveness among the public to prevent "catching" an infectious disease remains unsettled. Even so, the barrier of a mask may cut down exposure and prevent people from touching their faces as often. Therefore, the popular conception that masks are protective is not exactly a false one. They are commonly worn throughout Asia during influenza season.

But one thing we know for sure is that, to be effective, masks must to be used correctly. First, each should be worn for only a short period of time (a few hours or so) and regularly replaced with new ones because of the increased possibility of microscopic holes.

Second, masks must fully cover both the mouth and the nose. Experience demonstrates, however, that they can also give wearers a false sense of security and that people commonly adjust them to expose either the nose or the mouth — or both.

Masks for the public are also most effective when combined with other personal hygiene actions. In 2012, my colleagues Allison Aiello and Arnold Monto (at the University of North Carolina and the University of Michigan, respectively) conducted a mask study with college students during a regular influenza season. They found that, to be effective, masks must be worn consistently and early — as soon as flu season begins. The study also showed that masks work best in combination with other measures, particularly frequent hand-washing.

As many people now know, the thicker — and more expensive — N95 respirator masks work far better than regular "drugstore" masks. Because they fit tightly around the nose and the mouth, they are far more effective at blocking tiny viral particles.

Want more articles like this? Sign up for the THINK newsletter to get updates on the week's most important political analysis

But as I know from my years of wearing N95 masks, they are uncomfortable and difficult to wear for long periods of time. Medical professionals, though, are trained to deal with them. Right now, N95 masks are best reserved for health care workers on the front lines of the pandemic — American heroes who put themselves at risk of becoming infected.

Heroics were supposedly on display during the 1918 flu pandemic. The San Francisco mask story began on Oct. 18, 1918, when the flu roared back after a summer easing. San Francisco Health Commissioner William C. Hassler ordered all barbers to wear masks while cutting hair and recommended that all service workers wear them, as well. The next day, Hassler extended his order to include people working in hotels and boarding houses, bank tellers, pharmacists, store clerks and others in contact with the public. By Oct. 21, the city Board of Health issued a strong recommendation that all residents wear masks in public.

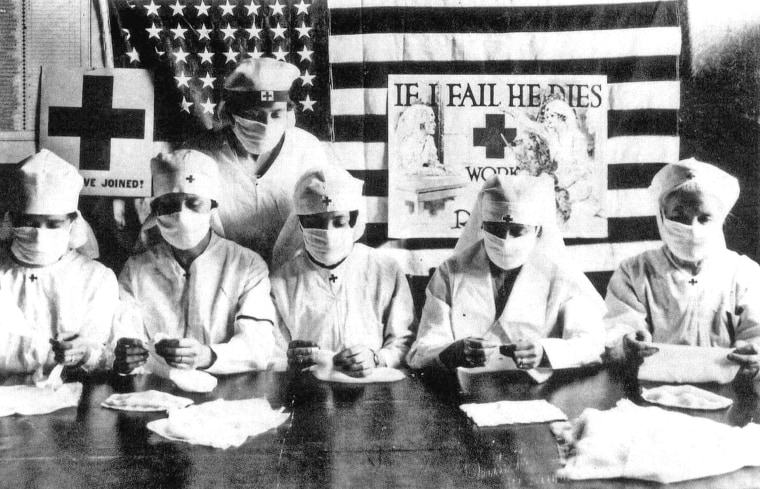

Mask wearing was considered a duty. A Red Cross poster declared that "the man or woman or child who will not wear a mask now is a dangerous slacker." California Gov. William Stephens doubled down, telling Californians it was the "patriotic duty for every American citizen" to wear a mask.

Although most San Franciscans complied, many didn't. So, on Oct. 25, every person in the city was legally required to wear a mask while in public or with two or more people, except at mealtime. Most of the masks were homemade, not mass manufactured or standardized. The materials were often even more porous and ineffective than the standard surgical gauze typically used.

Health officials and various mask "experts" made little distinction between the materials used. Dr. Woods Hutchinson, for example, crisscrossed the country to promote the mask's virtues as a means of preventing the spread of influenza. To entice fashion-conscious women, he told reporters, "chiffon veils for women and children have been as satisfactory as the common gauze masks." With supplies running low, the American Red Cross San Francisco chapter recommended that women make masks out of spare household linens.

Sadly, many still did not comply. Police began arresting slackers and issuing $10 fines. This squandered resources that would have been better used in helping the ill or preventing new cases. Two scofflaws were San Francisco Mayor James Rolph and Hassler, himself.

On Feb, 1, 1919, as the influenza finally waned, the city's mask ordinance was rescinded. But San Francisco, which opted for masks as its major preventive measure, still suffered the highest death rate of all major U.S. cities — approaching 30 deaths per 1,000 people. More than 3,000 died there in the fall and winter of 1918-19.

What lessons can we take from this masked history? Well, for one, mandatory public health laws have a checkered past in terms of compliance. In addition, Americans, then as now, did and do not like being told what to do. And most importantly, masks alone will not save us from a pandemic.

To come full circle, in 1918-19 Americans took comfort in wearing masks. Today, their descendants — many facing the first serious contagious crisis of their lives — may be taking false comfort in thinking these thin layers of gauze, paper and cloth will prevent their being infected by an invisible microbe.

So don't worry too much if you can't get hold of a box of masks. You can always fashion one out of a scarf or a spare shirt. For now, shelter in place and get your essential groceries and medical supplies delivered. And — as my dear, departed mother used to advise — try not to let anyone cough or sneeze on you.

Related: