Think of a gondola suspended under a cable, floating high off the ground as it hauls a cabin full of passengers up a long, steep mountain slope. To most people, the image would suggest ski resorts and pricey vacations. To the people who live in the poor mountainside communities once known as favelas at the edges of Medellín, Colombia, the gondola system is a lifeline, and a powerful symbol of an extraordinary urban transformation led by technology and data.

The technology that helped save Medellín is not what you'd see in San Francisco, Boston or Singapore—fleets of driverless cars, big tech companies and artificial intelligence. It is about gathering data to make informed decisions on how to deploy technology where it has the most impact. And it is about establishing a constituency for change that transcends wealth and class. When experts get together to discuss the path to smarter cities, Medellín often comes up as a standard against which any city's vision for transformation should be measured—including the judges of Newsweek's Momentum Awards.

Where most smart-city initiatives are of, by and, to a large extent, for the already tech-savvy and well-resourced segment of the population, Medellín's transformation has for the most part been focused on people who have the least. "Smart-city efforts tend to be centrally planned, with change driven by tech companies," says Soledad Garcia-Ferrari, an urban development researcher at Scotland's University of Edinburgh who has studied smart cities around the world. "Medellín looked for initiatives that are inclusive of every facet of society, and they were driven by the communities themselves."

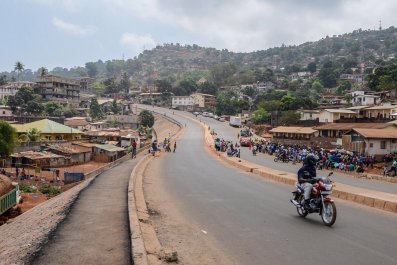

A city of more than 2 million that had long been renowned as a center of narcotics-related crime, poverty and despair, Medellín embarked on its smart-city journey in the mid-1990s, more than a decade before "smart city" was a thing. Progress since then has spanned five mayors of different political parties. Today, Medellín's homicide rate is one-twentieth of what it was in 1993, and nearly two-thirds of those who were once mired in poverty have emerged from it. Virtually everyone in the city, including the majority that a decade ago had few basic services, has full free access to education, health care, transportation and range of cultural, economic and online services, most of them free.

Along the way, Medellín's dramatic program of change has blurred the distinction between the technological and the humane. "This was all about innovation," says Carlos Moreno, a Medellín-born urban researcher at Paris' Panthéon-Sorbonne University. "But it was also about a shared vision of social innovation."

The key ingredient of Medellín's transformation, experts agree, is perspective: The city looked beyond technology as an end in itself. Instead, it found ways to integrate technological and social change into an overall improvement in daily life that was felt in all corners of the city—and especially where improvement was most needed. "Medellín's vision of itself as a smart city broke from the usual paradigms of hyper-modernization and automation," says Robert Ng Henao, an economist who heads a smart-city department at the University of Medellín. "It replaced them with a more anthropocentric vision of the city's future."

Out of the Dark

That vision was first forged in the crowded, destitute and crime-ridden mountainside neighborhoods of Medellín. Gangs allied to the Colombian narcotics cartels ruled by Pablo Escobar had met routinely in these favelas to exchange drugs and money and hand out kill orders. By 1993, however, Medellín's "dark period" was coming to an end. The cartels were crumbling. Escobar would die a few months later in a shootout with police.

That year, a few dozen people made their way to a small house that had been rented for the occasion. They were not gangsters. They were ordinary local residents invited by a coalition of government leaders, academic experts, civic organizers and corporate executives. The participants brought in books, assembling an impromptu micro-library. The idea was to read, sit around and relax, and, most important, talk. The main topic of conversation: how to fix Medellín.

The ideas that came out of this meeting, and others like it, formed the roots of the ambitious plans that would change the city over the coming decades. "Instead of rebuilding homes after a natural disaster, we were rebuilding society after a social disaster," says Jorge Pérez Jaramillo, dean of the School of Architecture at Medellín's St. Thomas University and chief planner of the city of Medellín for several years during the 2000s, under two different mayors. "The mayors never told us what to do. They saw their job as doing what the citizens told them to do."

The citizens told them to do a lot. Most residents still lived without basic necessities, such as sewage systems, clean water and schools. Their children had nowhere to play. Rains brought flooding and mudslides that washed away homes and even entire villages. There were jobs in the valley, but getting there from the mountains required a two-hour commute each way on multiple buses.

And no one felt safe. The dissolution of the cartels didn't end gangs and crime. The obvious solution would have been to flood the neighborhoods with armed police. But through those neighborhood meetings, the people of Medellín convinced the city administration to take a different approach: alleviating the poverty, isolation and lack of opportunity that led young people to seize on crime as their best pathway to success. "Instead of putting more guns on the street, they decided to invest in the poor communities and treat the residents like first-class citizens," says Boyd Cohen, until recently an urban strategist and dean of research at the EADA Business School in Barcelona, Spain, and now the CEO of urban-mobility-app developer Iomob. "That's how you change lives."

How should they pay for the programs that would save the city? In spite of its recent crime-ridden history, Medellín's economy had robust elements, including strong oil and clothing industries. Manufacturers were able to shoulder much of the burden in taxes, trusting that a city renaissance would provide a return on investment. To close the remaining gap, the city government looked to its public utilities company, EPM, which not only provided water, energy, telecommunications services and waste management to Medellín but also competed as a private company throughout Colombia and in other countries in Latin America and elsewhere. EPM would eventually boost its average annual contribution to Medellín's budget to $400 million a year. The city focused these resources on the program. Whereas cities in South America typically devote about a quarter of their budgets on development and services, Medellín has been dedicating, on average, more than half its budget on that spending since the early 2000s.

Rebooting the City

The various initiatives that emerged from those mid-1990s community meetings and panels of experts took years to implement, and in some cases decades. Proposals and studies started in 1995, including some for a gondola line, but the first tangible results didn't start to take shape until 2000, with the election of Mayor Luis Perez. He convinced the management of the city's Metro subway line, which is jointly run by the city and the Colombian state of Antioquia, to split the cost of building the gondola line with the city. Construction began immediately, and the gondolas started operating in 2004, cutting the commute time for residents of the poor mountain communities to their jobs in the city center, from two hours down to 20 minutes. That original line carries 30,000 people a day, and since it opened, four additional gondola lines have started operating.

Under Medellín law, mayors can serve only one four-year term. In 2004 Perez turned the reins of the city over to Sergio Fajardo, a mathematics professor and the son of an architect. Fajardo campaigned door to door in the city's poorest neighborhoods, promising to let the people make the big decisions about spending on new projects. He kept his word, and during his term he frequently solicited and followed the guidance of neighborhood councils to set spending priorities.

Under the local councils' direction, Fajardo revamped the city's education system, putting 20,000 teachers through additional training at special centers that focused on innovative teaching approaches. All children now have free access to local after-school programs that include courses in culture, science and technology, and language learning. Initiatives to guide more young people away from crime pulled thousands of young children a year out of the gangs, and efforts at raising the rates of college education directed tens of thousands of young people to one of the city's 30 universities and technology training centers. Fajardo also upgraded health care, with extra attention for children, initiating child care centers that offer health and nutrition services to young children and their families.

Fajardo also won the councils' support for projects aimed at improving the city's cultural and quality of life. The city began adding what would eventually amount to more than 4 million square feet of public space for a variety of uses, including the building or renovation of 40 public parks. Fajardo authorized the building of the Spanish Library Park, a massive, contemporary library surrounded by green space at the mountaintop that just happens to be the site of the end of the city's first gondola line. That park, close to poor communities, has become a global tourist draw, along with a 50-mile stretch of highway along a river that has been converted into a greenway. Fajardo also directed the creation of one of the world's most popular science museums, funded primarily by city businesses. EPM, the utilities company, built a second massive library.

Even though Fajardo had to step down at the end of 2007, his initiatives and community-driven style were so popular that it became virtually impossible for politicians who followed him to win election without promising to keep the projects coming.

Fajardo's immediate successor, Alonso Salazar Jaramillo, built a series of outdoor escalators into the hills that are as long as 1,200 feet each, reaching tens of thousands of other poor mountainside residents who aren't close to gondola stations. He also expanded the park and library systems and the cable lines, and he continued investing in improved education and health care.

Salazar brought a more explicitly high-tech, digital perspective to the ongoing stream of improvements—targeting, for example, the city's choking and outright dangerous car traffic. By 2009, 40 cameras at the most accident-heavy intersections were keeping watch over 1 million cars a day, flagging speeders, red-light runners and reckless drivers who swerve between lanes. The system reads the license plates of offenders and fires off tickets via mail, cutting violations between 2009 and 2014 by 80 percent. Another 80 smart cameras detect accidents or disabled vehicles causing jams, calling them to the attention of police and other services. Altogether, more than 800 cameras watch Medellín's roads for trouble of any sort. Twenty-two electronic messaging boards throughout busy areas provide drivers with up-to-the-minute guidance on the best routes.

Under Salazar, the city began to build and nurture a digital economy to reduce its dependence on manufacturing. It set up an innovation district, called "Ruta N" (Route N), and provided offices, seed funding, expertise and other support for high-tech startups. It also helped broker partnerships between Ruta N companies and larger tech companies, and it lowered the bar on the requirements needed for companies to bid on city projects to ensure that even tiny startups would have a shot at contracts. Salazar earmarked 2 percent of the city budget for Ruta N companies and other efforts at fostering innovation. Partly as a result of these efforts, more than 170 companies from 25 countries have set up operations in Medellín, generating nearly 4,000 new jobs in just the past three years.

Aníbal Gavaria Correa, who took over as mayor in 2012, set up a series of programs addressing dangerous flooding and mudslides, installing sensors that monitor rain, water levels, soil moisture and soil movement on hillsides throughout the city. This provided earlier, more precise warnings of where flooding and other catastrophes might occur. Citizens in villages who were at risk of floods and slides could use smartphone apps that let them supplement sensor data with their own observations and pictures of potential hazards. Planners used the data to locate drainage pipes and other conduits to direct excess rainwater away from vulnerable areas.

A lack of access to Wi-Fi sidelined many city residents on the mountainsides and elsewhere from the online revolution. So the city set up more than 150 public Wi-Fi zones, which are free. In addition, it put free computers in more than 500 locations where residents could get access to them, and it established 48 internet-education centers offering free classes. Two-thirds of the city's lowest-income residents now have smartphones, and almost 500 companies have agreed, under Gavaria's encouragement, to allow employees to work remotely via telecommuting, helping alleviate traffic.

Under Mayor Federico Gutiérrez Zuluaga, who took office in 2016, the city established online programs that offer education and personal advice to pregnant women and new mothers. A new citywide online system was set up in order to easily make any sort of health-related appointment at a hospital or clinic, and a revamping of health care emergency services cut response times by 37 percent. The city also built dozens of new sports facilities focused on youth participation. To continue the city's mobility improvement and cut down on pollution, Gutiérrez added 64 electric buses and a citywide free bike-sharing service, along with 60 miles of separated bike lanes.

To make it easier for citizens to interact with the city government, Gutiérrez placed access to the vast majority of city and utility services online. Almost any service can now be started, changed, stopped or paid for from a web-browser or smartphone. Residents can get online updates on city legislation, policymaking and projects. And they can interact with city officials in a variety of ways, providing a valuable input for city leaders and administrators and allowing communities to directly participate in decisions about how some of the city's budget is spent.

Smart-city-related efforts have helped rocket Medellín from its grim situation in the early 1990s to its current status as a city with some of the lowest rates of poverty and crime—and highest rates of education and health care access—in South America. Residents' sense that they have actually helped make decisions that moved Medellín toward these improvements has been a critical part of the process, notes Edinburgh's Garcia-Ferrari. "Smart-city solutions need to be combined with this sort of participatory platform," she says.

No one claims that Medellín's transformation is a finished project. While the poverty rate has plunged over the past 20 years from its highs of 48 percent, in recent years it has leveled off at a still troubling 14 percent. But there's great satisfaction in what's been done so far—at least to judge by the mayoral election at the end of October. That election saw the surprise resounding defeat of a right-wing candidate whom many have compared to Donald Trump. The victor, Daniel Quintero Calle, a former Colombia deputy minister of the digital economy, campaigned on continuing previous mayors' investments in education, infrastructure and high-tech initiatives aimed at especially benefiting the poor and vulnerable. Apparently, Medellín is not ready to cut short the renaissance that claims a gondola as its emblem.