From our Old Bike Archives – Issue 84 – first published in 2019.

Story: Peter Laverty • Photos: Jim Scaysbrook

There’s no doubt that Yamaha’s retro racer SR500, introduced in 1978, was a bold move, and after an initial wave of nostalgia-fuelled buying, sales tapered away rapidly. After all, it was slow, difficult to start, and, in an era of multi-cylinder rocket ships, more than somewhat of an anachronism. Yamaha was chastened, but not completely discouraged with the overall concept; perhaps all that was needed was a re-think. A major re-think. What happened eight years after the SR500’s debut was a motorcycle that owed just one thing to its predecessor – the fact that it was a single cylinder four-stroke.

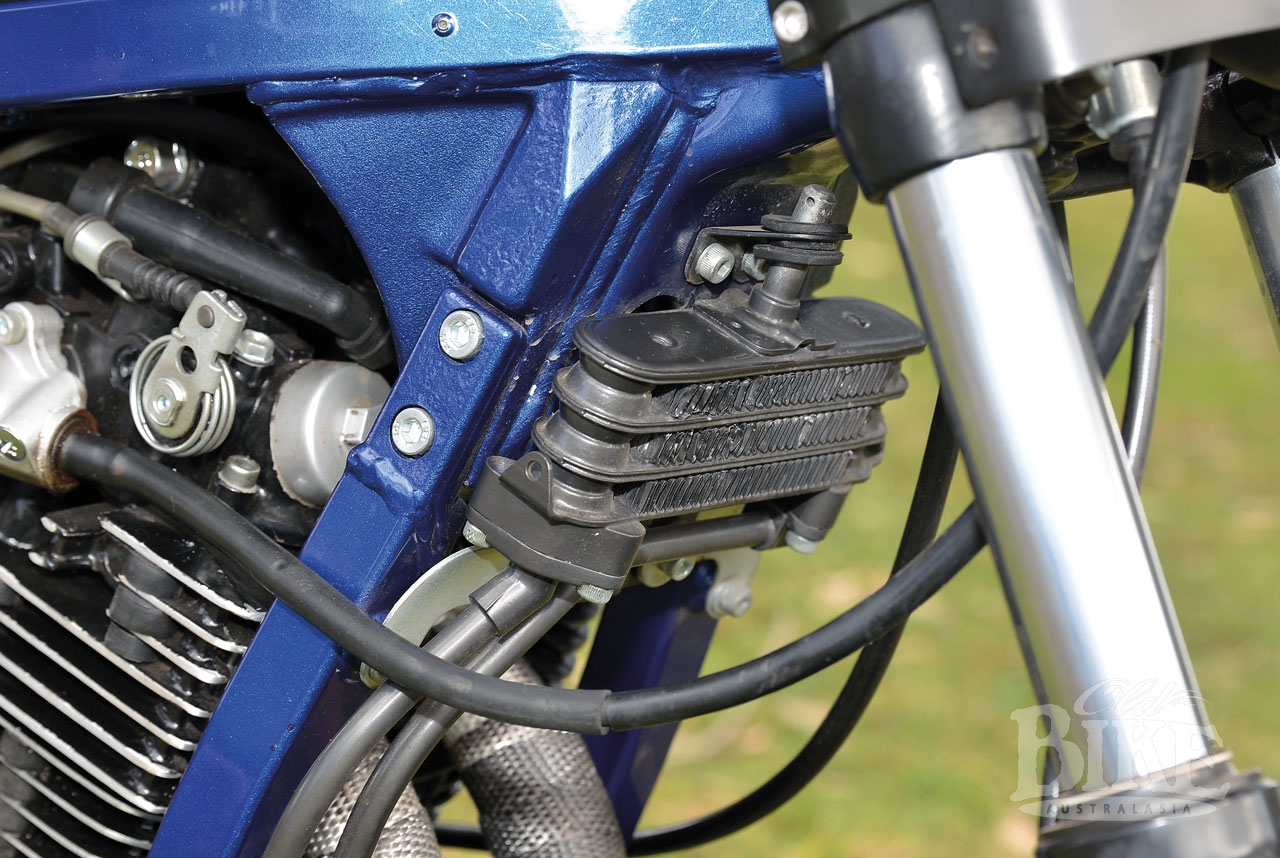

Gone completely was the salute to the British singles of yore. The new machine – dubbed SRX600 – was a whole new slant on the big single. Beginning with the powerplant, here was a 608cc, single overhead cam, four-valve donk that had its origins in the on/off-road XT600E (with 1mm smaller bore to produce 595cc), with more power (although still not of the neck-snapping variety), a gear-driven balance shaft, CDI ignition, two-stage carburettor, and very nice five-speed gearbox with a light, responsive clutch. Basically taken from the XT600 set up, the ‘dual’ carburetion saw one, slide-operated carburettor body directing mixture to one of the inlet valves for low rev running, after which the second, constant velocity carb kicks in, feeding the second inlet valve. Although slightly up-spec from the XT600 engine, the SRX had actually been ‘down tuned’ from the off-road Teneré, with 1mm smaller inlet and exhaust valves, and a lower-lift camshaft. The result was smooth, progressive power, although not enough of it.

This mill was slotted into an all-new frame made from square-section steel tubing, with detachable bottom frame rails to enable the engine/gearbox unit to be dropped out. Considering that by this stage, Yamaha frames were synonymous with their patented, Belgian-designed ‘Cantilever’ rear ends, the choice of twin shocks mounted on a rectangular-section steel swinging arm was curious. Front suspension, on the other hand, came almost directly from the RD400, along with the twin front discs, and single rear disc. Much of the electrical components were also sourced from existing Yamaha models. The large circular 60/55 Watt headlight dominates the front end, and the little black-faced tachometer, jammed in beside the white-faced speedo, looks a bit of an after thought.

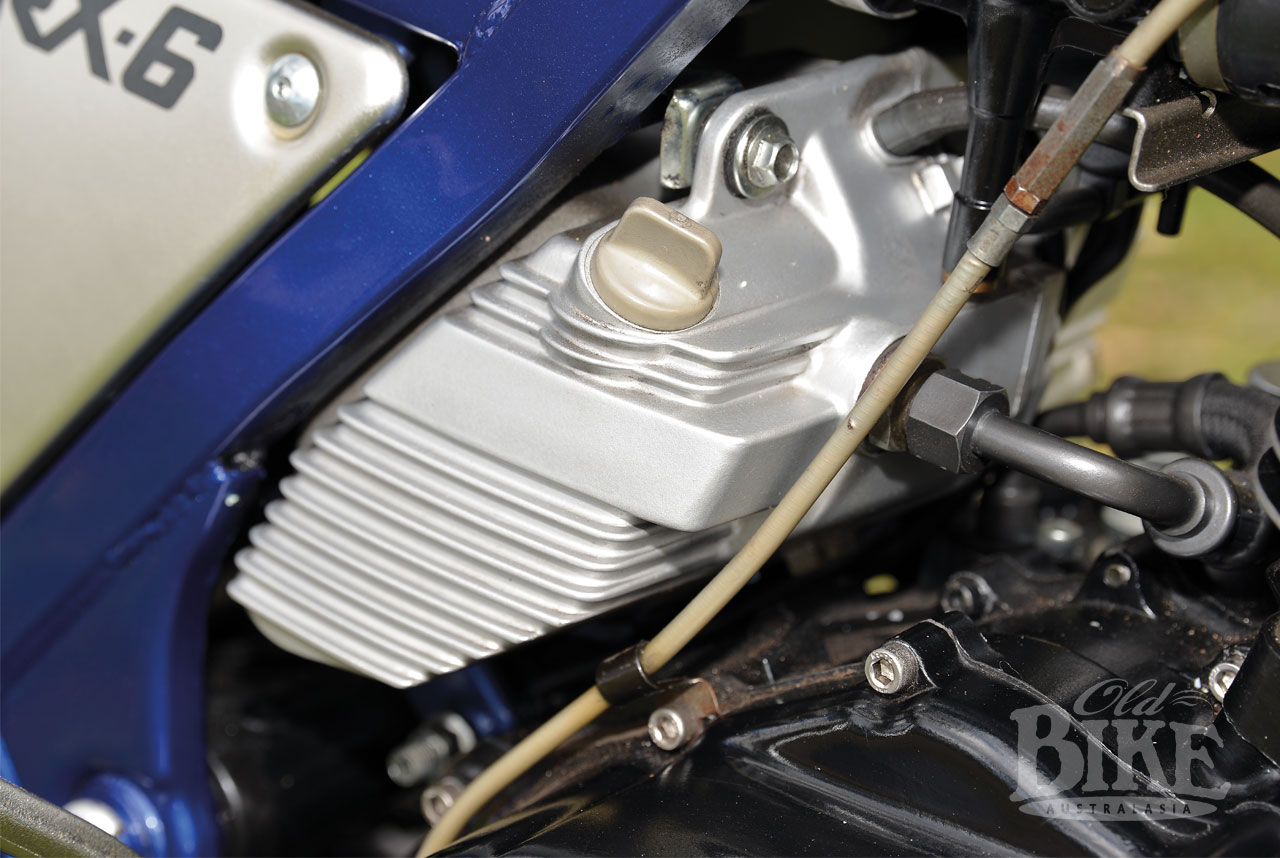

Although sporting a normal dual seat in catalogued form, other touches nodded to the café racer element; alloy clip-on handlebars, footrests and foot controls set to the rear, a quirky alloy oil tank with cooling fins that carried 2.4 litres of lubricant, and a wonderfully sculptured fuel tank (with flush-fitting cap – handy for a tank bag) that sat above the top frame rails and placed the majority of the fuel load low and in the centre of the bike. To the despair of many, there was still no electric button for starting, but the kick-starting process that had defeated so many on the SR500 had been refined to the point that it was now dead-easy thanks to the automatic cylinder decompressor. Just move the kickstarter around the arc slowly until you hear a ‘click’, which means the mechanism has set itself, return the kick starter to the top of its travel and follow through in a graceful boot. That should do it. Oh, and from cold, don’t forget the choke.

A sign of the times was the massive collector box below the engine, into which the twin exhaust pipes from the cylinder head entered, with a single stubby silencer emitting a disappointing wheeze; nothing like the bark of a Goldie or Thruxton. The overall length of the exhaust system was able to be kept short due to the fact that much of it wound backwards and forwards inside the collector box. It also precluded the fitting of a centre stand.

Initial road tests were coy at best regarding the power. ‘Civilized’ is a word that smacks of politeness rather than truth. Torque was nothing to shout about, and the engine was unhappy below 2,000 revs in the upper gears, which meant a down-change below 60 km/h in top gear. Many felt the overall gearing was too tall, which retarded acceleration and mid-range power, and meant that the engine would struggle to hold any more than 5,500rpm in top gear. Although 172 km/h top speed was claimed, none of the tests could coax much more than 160. Handling however, came in for universal praise, as did the suspension and brakes. The SRX did have a formidable rival in the Honda GB500, which although 100cc smaller, was a match in performance and also cheaper. And it had an electric starter. In fact, in America, the SRX sold for the same price as the four-cylinder 650. No contest.

As always, the truth lay in the sales figures, and whichever way you looked at it, the SRX bombed in the vital US market where it was sold for just one year. For US dealers, memories of the sluggish-selling SR500 were still raw. Many questioned why the SRX engine, closely derived as it was from the electric start Teneré, had dispensed with the button, which was a fair question. The British, on the other hand, took quite a shine to the SRX, one magazine even labelling it, “a modern Ariel Red Hunter”. Brickbat or bouquet? In all, production reached just 19,000, the majority of which were sold in 1986, although the model struggled on in some markets until 1991, by which time it had gained 17-inch wheels and more modern tyres front and rear, and single shock rear suspension. In Japan, the 400cc version did a six-year-stint. There was a distant cousin SRX250 as well.

Yin and yang in SRX600 terms.

Here we will look at a pair of Sydney-based examples of Yamaha’s big road single; blood brothers but poles apart in execution. The standard-spec model belongs to Garry Appleyard, former president of the active Macquarie Towns Restoration and Preservation Club and a regular on club runs and rallies, while the blue beauty is the work of Glenn Besso, and a damn fine job it is too.

“It was a pig to start!”

Garry Appleyard’s 1986 SRX600 is in completely standard specification with the exception of the seat. “The original seat is flat and slopes forward, so I find this pushes you into the tank, which can be a bit painful, especially when you are carrying a passenger,” says Garry. The one that is fitted now I had modified using another base and it has a humpy tail that you can tuck back into when riding solo, which I now do and for this reason I have taken off the rear footrests. I bought the bike from Max Conley’s shop in Orange about 1989 when it had just 1,460km on it, so it had hardly been used.

“It was a pig to start so I took it to John Fretton’s Yamaha shop in Sydney and they changed a few things and it was much better. However one thing I discovered through a family connection at BP was that the engine was completely unsuitable for 98 octane unleaded. They explained that the core spark plug temperature needed to reach 500ºC before it would start, and with a kickstarter this was near impossible. It also ran the risk of detonation and I believe a lot of people make the mistake of using 98, even in modern bikes. Once I switched to 95 it was fine. Once it is warm it will start first or second kick. It is difficult to get it into neutral when it is warm, which is a bit annoying until you get used to snicking it in before stopping. The balance shaft in the engine clatters a bit when cold but is quiet after it warms up. The gearbox is very well made, with the oil delivered through hollow shafts and holes in the gears, but the overall gearing is a bit tall and you need to hang onto fourth gear up to about 90 km/h before changing into top. There’s plenty of torque but you can’t hold 5th gear under 3,000 rpm – top really is just an overdrive. I have a mate who has a 500 BSA Gold Star and at a rally we decided to see how it compared with the Yamaha. In acceleration, the Yamaha was easily quickest but once I got to about 90 I could hear the BSA coming and it just went past me. The Yamaha sort of runs out of steam in terms of top speed. At one stage I thought of selling it but now all the bugs have been ironed out and I only use it on two or three rallies per year, I’ll hang on to it because overall it is a very pleasant bike to ride.”

Back in blue

Glenn Besso did not set out to simply restore his SRX600 to standard trim, quite the opposite in fact. He saw many areas that could be improved, either in functional terms, or simply to his own tastes. Given that he started with a fairly tired old motorcycle, he had a fine pallet on which to express himself.

“My Yamaha SRX600 is a grey import brought in (to Australia) from Japan in 2006,” says Glenn. “It is a 1987 model year made specifically for the Japanese market. It has a Queensland Transport compliance plate with a Vin/Chassis number generated by them as this bike does not have one from the manufacturer. I purchased the bike in 2017 as a non-runner, in very poor condition. The engine needed a full rebuild and the cylinder head had been damaged beyond repair, requiring replacement. A second hand head was sourced from a bike wrecker in the UK and was refurbished with new valves, guides and seals as part of the engine rebuild. The barrel was rebored by Duncan Foster in Blacktown (Sydney) to accept a 2mm larger Wisco high compression piston (giving 633.6 cc). A Competition clutch was installed to deal with the extra torque, only as a precaution though, as the standard clutch is excellent and would probably have coped”.

If there is one word that pops up repeatedly in road tests of the original SRX600, it is ‘breathing’, and not in a positive sense. The general opinion was that in order to cope with the emission regulations as they were in the mid ‘eighties, both the induction and exhaust efficiencies were severely compromised, but legal. Glenn set about rectifying this.

“A 42mm Mikuni carburettor was purchased and a two-into-one manifold from a Yamaha Grizzly was fitted to replace the standard Yamaha dual carby system. Unfortunately the oil tank occupies the real estate required to fit the large single carburettor so the original was re-kitted, painted black and put back into service. The air box was discarded and replaced with a K&N filter on the primary carb and a velocity stack on the secondary. The standard exhaust system has been replaced with dual, un-baffled stainless mufflers; one for each header pipe exiting the twin-exhaust port head.”

Handling on the stock SRX600 is generally regarded as excellent, but there is always room for improvement, as Glenn explains. “The forks were rebuilt with new seals but the standard springs retained in favour of using the air caps to adjust the preload. 10 PSI gives a very good feel and feedback for my weight along with the reduction of overall weight of the bike from standard. Around 28kg has been reduced by replacing or removing the following components; headlight, exhaust system, air box, seat assembly and part of the frame support, tail light assembly and rear foot peg hangers. The Japanese model also runs a single disc front end with the lighter 3 spoke wheels which reduces unsprung weight but retains excellent brake feel and power. In fact it is probably over-braked given its very light overall weight.”

The quest for lightness extended into the chassis itself. “The frame was de-cluttered of all redundant mounting tabs and brackets, then sand blasted and powder coated in intense blue. The brake calipers and engine brackets are finished the same way. The front guard, fuel tank and seat cover are finished in a matching colour. The fuel tank is two-toned; carbon grey fading into blue from the centre to each side. All the components previously listed including the wheels, brake stay, instrument brackets, chain guard, engine side cover and triple clamp were coated in a carbon fibre finish by Just Dip It in Glendenning (Sydney) followed by a coat of 2 Pack clear.”

A distinguishing and deliberately retro feature of the original SRX600 was the large headlight with its chrome plated shell and polished alloy brackets, but that has been changed as well. “Projector headlights replaced the original single head light and bucket, with a three-in-one LED tail, brake, indicator and number plate light, concealed in the cowling, replaced the rear unit. Tyres are Dunlop Arrowmax on tubeless rims with right angle valves.”

The result is a stunning and purposeful looking motorcycle, which, although unique, retains the basic geometry of the original. “Of the sixteen motorcycles I own, this has become one of my favourites to ride due to its excellent road holding and comfortable, effortless charm. I believe this is one of many underrated motorcycles the market overlooked, probably because it does not have an electric start. They did introduce an electric start model later, but maybe single cylinder motorcycles can only be truly appreciated by those who own them.”

Specifications: 1986 Yamaha SRX600

Engine: Single cylinder, single OHC, 4 valves. Dry sump.

Capacity: 608cc

Bore x stroke: 96mm x 84mm

Compression ratio: 8.5:1

Cooling: air cooled

Induction: 27mm Teikei 2KY27PV carburettor

Ignition: CDI

Starting: Kick

Transmission: 5 speed

Power: 45hp @ 6,500 rpm

Torque: 46Nm @ 5,500 rpm

Final drive: Chain

Suspension: Front: 36mm telescopic forks. 134mm travel.

Rear: 2 x Kayaba shocks with 5-way preload adjustment 100mm travel.

Brakes: Front: 2 x 267mm discs with opposed-piston calipers. Rear: 1 x 240mm disc with single piston caliper.

Wheels: 3 spoke cast aluminium

Tyres: Front: 100/80 x 18 Rear: 120/80 x 18

Wheelbase: 1380mm

Seat height: 770mm

Dry weight: 155kg (176kg wet)

Fuel capacity: 15 litres

Top speed: 172 km/h

Price new (Australia 1986): $4,899.00 + ORC