Fallingwater: Critical Response

Great architecture, like any kind of great art, ultimately takes you somewhere that words cannot take you at all. And Fallingwater does that the way Chartres Cathedral does that. That there’s some experience that gets you in your gut and you just feel it. And you can’t quite even say it. My whole life is dealing with architecture and words. And at the end of the day, there’s something that I can’t entirely say when it comes to what Fallingwater feels like. I remember the first time I went to Fallingwater, taking a long walk down, looking at it from across the waterfall and you just wanted to sing. Just looked at it and you wanted to start singing some song or doing something. There was nothing really to say. It was so extraordinary.—Paul Goldberger, Architecture Critic

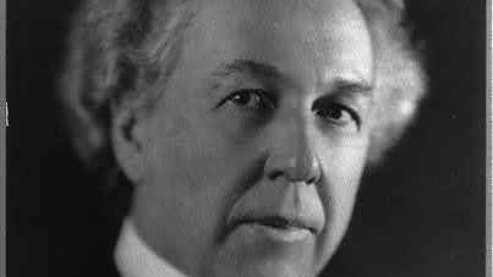

Spring Green, Wisconsin: Frank Lloyd Wright the venerable dean of modernism in American architecture, has recently designed a dozen structures which are now being planned or built in eight states. A country house straddling a waterfall. A spacious and stately office that breathes through nostrils and fixtures, street doors or windows—the word is usually understood. A fabricated house to cost a little over $5000 and be as expansive and luxurious as the architect thinks any house has a right to be. These will seem the most startling innovations.

Not to their architect, though. They culminate and express principles, ideals, experiments and a common-sense artistic logic that Frank Lloyd Wright has been living with for most of his 68 years. Long ago he built a Pasadena house inside the rim of a ravine. As far back as 1903 he built the first air conditioned, possibly the first fireproof, office building—the Larkin Building in Buffalo, New York. Over the active span of his fiercely creative years, he has designed many houses containing some of the principles that must go into any lowcost factory built house. Bold originator that he is, all Frank Lloyd Wright’s building is the product of what he considers a leisurely and relentlessly logical inner growth of ideas.

Test this against the waterfall house, which is being built for Edgar Kaufmann, a wealthy merchant of Pittsburgh. It is still under construction in Bear Run, a luxuriantly wooded ravine in southern Pennsylvania’s Alleghenys. Though it’s probably true that no house very like this has ever been built anywhere, this one didn’t spring full-blown from the architect’s imagination. When finished (probably in June) it will seem to have grown by a natural process of geology out of the boulders of Bear Run.

St. Louis Dispatch, 1937

“A House That Straddles A Waterfall”

Walking over the ground, with his client, Wright said: “You love this waterfall, don’t you? Then why build your house miles away, so you will have to walk to it? Why not live intimately with it, where you can see and hear it and feel it with you all the time?” Had Edgar Kaufmann been the sort of man who couldn’t understand that idea, he would have contested the point. But in that case, he would never have asked Wright to design his house. As it was, he objected only that this would be an impossible engineering feat.

“Nature cantilevered those boulders out over the fall,” the architect answered. “I can cantilever the house over the boulders.”

In other words, the house will be a series of stone and concrete shelves jutting out over the 30-foot curtain of tumbling brook. The stream that scrambles sparkling down the path of rebellious boulders behind and above it will pass tinkling underneath. It will be gathered into a swimming pool by a tall dam and the house will be set neatly into the steep banks, in spring a tapestry of rhododendron blossoms, that rise abruptly on either side.

Inhabitants of the waterfall house will see the pool falling away under the living room through a huge glass hatchway fitting into the floor. They will lift the hatch and walk down a flight of banging steps to the pool for a morning dip. A flight below they can shower off in the stinging mountain water of the fall itself.

Their house will not shut out the forest. It will embrace tree trunks that spring up through cuts in the balconies. It will reach out into the branches and no wall will interrupt the view. The woodland panorama will be framed in windows that are merely commodious bands of glass with glass door panels opening onto the parapets flanking every room.

Rising through the concrete shelves, which will probably be trimmed in dull gold leaf—the quiet gold of Japanese screens, the natural rock of the surrounding hills will be laid in flat horizontal layers rising squarely. These rocks will make the piers and generous high chimney, and while parts of them will be plastered inside, no attempt will be made to line the house in such a way as to disguise its fabric and texture. A huge flat, boulder around which the lowest shelf fits snugly will be the living room hearth, for instance. The living room will be a living room in fact, suitable for every function of life except those to which bedrooms, bathrooms and kitchens are devoted. It will sweep forward from the natural wall of the cliff itself out into the landscape visible day and night through steel framed “glass screens.” A stairwell penetrates the house from the glass hatchway set in the living room floor to the top terrace, the third floor, which levels off to the embrace of the surrounding cliffs and touches the earth of the hillside curving above.

On every side on is conscious of the intimate way the whole building falls cozily back into the ravine and the bold manner of its jutting forth over its bowl.

Because this is all diametrically opposed to the way most people build their houses, many decent citizens will find this house unexpected—hence distasteful. Others, according to Wright, more clever and up-to-the-minute, will beam on it—“Ah, functionalism!” Both attitudes will be unsympathetic. Both uncritical.

Reprinted with permission of the St. Louis Post-Dispatch, © 1937.