This article was featured in One Great Story, New York’s reading recommendation newsletter. Sign up here to get it nightly.

He called 911 after it happened. “My wife is an artist and I am an artist and we had a quarrel about the fact that I was more, eh, exposed to the public than she was,” he told the dispatcher between sobs, “and she went to the bedroom and I went after her and she went out of the window.”

It was the early morning of September 8, 1985. When police arrived at Carl Andre and Ana Mendieta’s apartment on the 34th floor of a Greenwich Village high-rise, Andre told them, “I think she jumped. I just know.” A few hours later, when he made a statement at the precinct, he said Mendieta either jumped or fell: They’d been watching a movie at around 3 a.m. She went to bed first. When he followed half an hour later, she was gone and the bedroom’s sliding-glass windows were open. Decades later, in an interview with the New Yorker, Andre remembered the night this way: He said that he was half-awakened by a woman’s voice yelling “No, no, no!” The temperature had dropped in the small hours, he said, and his hunch was that his wife, Mendieta — who was only four-foot-ten — had climbed up to close the high windows, lost her balance, and plummeted to her death.

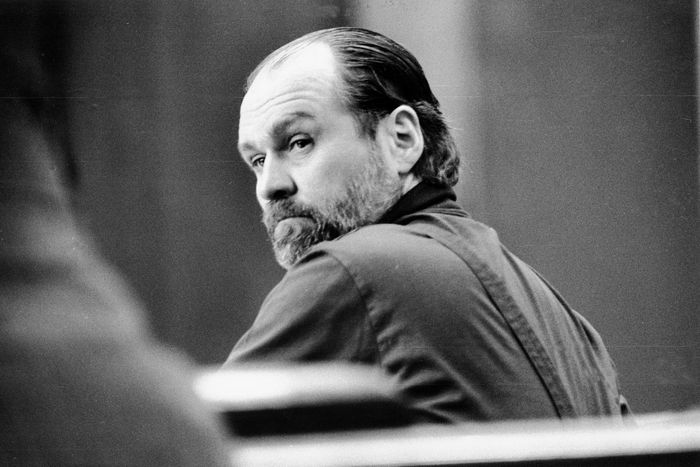

After a two-and-a-half-year investigation, Andre was charged with Mendieta’s murder. By early 1988, he had been acquitted. The trial drove battle lines through the New York art world, and stories about Mendieta’s death tended to emphasize the star-crossed nature of the union: Mendieta was a 36-year-old charismatic Cuban exile. Less famous than her husband at the time, she’s now remembered through documentation of her visceral, site-specific performances using mud, flowers, feathers, fire, and blood. Andre, a New England Marxist 13 years her senior, was then a god of the avant-garde — one of the first minimalist sculptors to work with industrial materials like bricks and tiles and, as a onetime leader of the labor-organizing Art Workers’ Coalition, a rare militant among the blue-chip set. Both were drinkers. Andre’s defenders said he wouldn’t have been capable of killing his wife, while Mendieta’s said she wouldn’t have jumped: Not only was she terrified of heights, she was starving for art-world fame and felt she was this close to attaining it. One onlooker at Mendieta’s memorial described the event as being like a wedding from hell, with attendees divided into families who avoided eye contact.

Whether she would have liked it or not, Mendieta’s death made some people see her as a martyr. And though he was not found guilty of causing it, it made Andre a pariah, at least in some circles. When a traveling retrospective of his work opened at L.A.’s Museum of Contemporary Art in 2017, protesters came to hand out postcards that read, “Carl Andre is at MoCA Geffen. ¿Dónde está Ana Mendieta?” — where is Ana Mendieta?

At the time, the art historian Helen Molesworth was MoCA’s chief curator. Now she’s the host of Death of an Artist, a podcast about the Mendieta-Andre story by Pushkin Industries and the Sony studio Somethin’ Else. The show doesn’t draw conclusions about what happened that night at 300 Mercer Street, #34E. Instead, it lays out the puzzle pieces of Mendieta’s death for listeners to assemble, weighing the scenarios that could have led to that moment. The podcast’s most novel element is its analysis of what came after Mendieta died: the war of ideas waged by lawyers, artists, journalists, critics, and activists that turned her from flesh and blood into the loaded symbol she is today.

Few people have had a better bird’s-eye view of this conflict than Molesworth. When I asked her what it felt like to be at MoCA during the Andre protests — to be seen as a defender of the status quo — she paused, then said, “I wish I’d been braver.” The curator didn’t respond to the protests publicly at the time; the next year, she was fired from the museum. (She signed an NDA on her way out, but sources close to the museum told Artnet that Molesworth and other colleagues objected to the show behind closed doors. The artist Catherine Opie, who is also a MoCA board member, said that the museum director told her they had fired Molesworth in part for “undermining the museum” — a decision Opie disagreed with.)

When Molesworth took on the assignment of hosting the podcast, she waded into the controversy directly. “I assumed enough time had passed, and that I was trusted enough that people would talk,” she said. “Wrong.” According to her, Mendieta’s family members have a no-comment policy when it comes to projects that focus on the artist’s death. (Mendieta’s niece, Raquel Cecilia Mendieta, told Vulture that Mendieta “felt the work should speak for itself, and this has been my beacon when it comes to decisions on whether or not to participate in conversations about her and her work.”) Andre’s approach has been to say as little about the incident as possible. Molesworth and her producer, Maria Luisa Tucker, attempted to get in touch with him anyway, without success — they even waited in the lobby of his apartment building and passed a note to his doorman. (I also contacted Andre for comment and received no reply.) Failing that, they reached out to people close to him, such as his influential longtime dealer, Paula Cooper; she didn’t want to talk either. Most of the people who appear on the podcast — including Mendieta’s best friend, Natalia Delgado — believe that Andre killed Mendieta. As the reporter Joyce Wadler, who covered the case for New York, told me, “In crime stories, the family of the victim is eager to talk. The family of the accused tries to push you off the porch.”

In order to reconstruct the New York art world of the 1970s and ’80s, Molesworth and Tucker worked with archival interviews as well as new ones, plus clips from Mendieta’s letters read by the Cuban artist Tania Bruguera. The tapes from the trial were sealed in 1988, under a law that protects defendants who are acquitted of crimes. Luckily, the journalist Robert Katz, who published a book about the trial in 1990 and died in 2010, had copied the tapes while they were still accessible and left his archive of notes and recordings with a library in Tuscany.

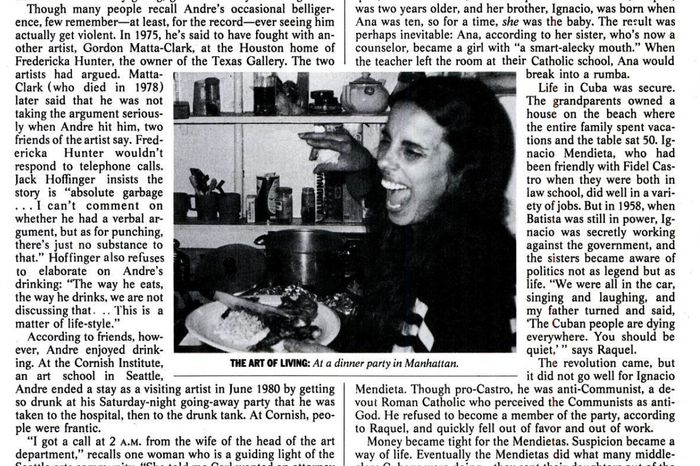

Even before the trial, Andre’s supporters, at nightclubs and cocktail parties, began to gossip about Mendieta. In her 1985 New York story, Wadler quoted an unnamed woman in the art world who said there was a “whisper campaign” coordinated by art-world illuminati to make Mendieta seem like a “loony Cuban.” On Molesworth’s podcast, former Village Voice critic B. Ruby Rich — Mendieta’s friend and one of Andre’s most outspoken accusers — discusses how Mendieta was framed at the time. “It was totally blame the victim, but with an extra twist,” she says. “It was completely racist. It was constructing this idea of the hot-blooded Latina who drank and misbehaved and quote-unquote went out a window.” One unnamed source in Katz’s book, identified as a friend of Andre’s, said the artist’s accusers were a “feminist cabal” blinded by their vindictive resentment toward men. Artists like Frank Stella were among those who put up money for bail.

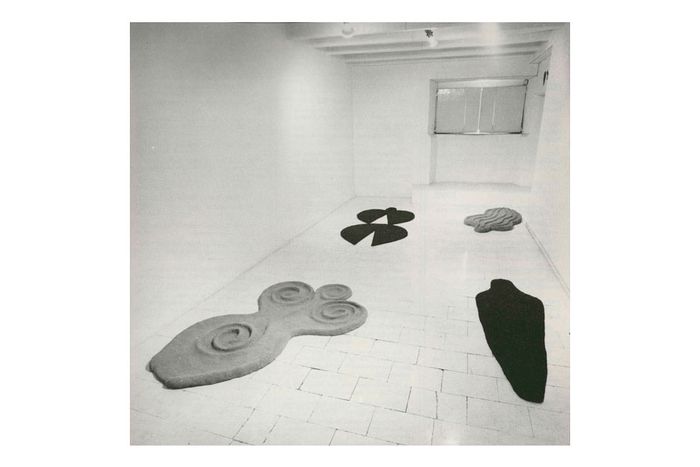

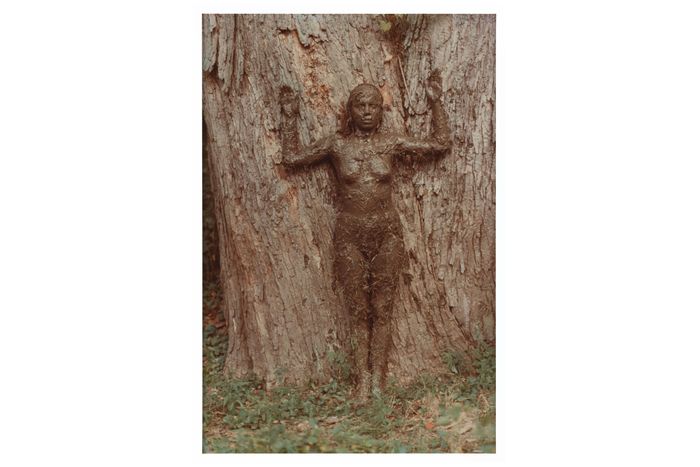

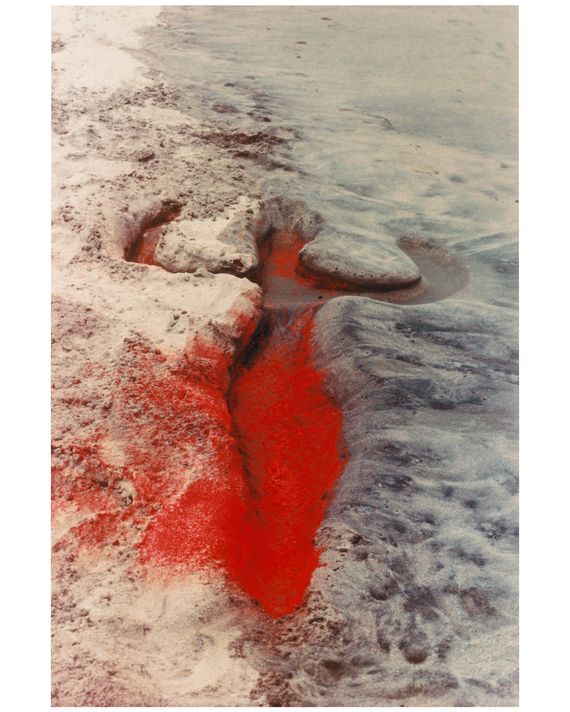

One of the most shocking takeaways from the podcast is that lawyers and art critics alike used Mendieta’s work against her. Mendieta pioneered a genre of her own called body-earth art and is often remembered for her “Silueta” (Silhouette) series: photographs and films depicting life-size angel shapes that she dug, carved, or burned into nature. For one untitled photo from 1976, she inscribed one of these silhouettes — a seemingly ancient symbol, like a Mesopotamian goddess — on the shoreline of a Mexican beach, then filled it with magnificent red paint and let the tide wash it away; for another, from 1973, she lay prone on a rooftop covered in a blood-spattered sheet, with a cow heart sitting on her chest. Mendieta herself said that, with these works, she hoped to visualize the hidden continuities between our bodies and the natural world: “These obsessive acts of re-asserting my ties with the earth are really a manifestation of my thirst for being.”

However, during the trial, Andre’s defense lawyer, Jack Hoffinger, called witnesses to the stand — including hotshot critics and curators — to testify that Mendieta’s art practice indicated a ritualistic death wish. Some of Hoffinger’s questions focused on her interest in Afro-Cuban Santeria. Mendieta had named one of her Siluetas after the deity Yemayá, and Hoffinger solicited one friend of the artist’s to explain its significance. When the friend said that Yemayá was known for taking flight, Hoffinger asked when Yemayá took flight. September 7, the witness said — the day before Mendieta’s death. Never mind that this testimony was flat-out wrong, as Molesworth points out in the podcast: Yemayá is a water spirit and a protector of women, with no relationship to flying or flight. It was enough to suggest that Mendieta had a dark side. “It’s as if the art critic were some two-bit dime-store psychologist,” Molesworth told me.

While Mendieta’s work is often mentioned in the same breath as her tragic end, her art has also continued to speak for itself. It has enjoyed numerous revivals over the past two decades, including survey shows at the Chicago Institute of Art and the Hirshhorn in D.C. She was one of the main attractions at the blockbuster show Radical Women: Latin American Art, 1960–1985, which made it to the Brooklyn Museum in 2018. In the years before she died, the New York art world was dominated by two gangs: minimalists like her husband, with their experiments in the metaphysics of form, and Pop artists like Andy Warhol, with their cynical ideas about the commodity fetish. Mendieta, meanwhile, was making art about the interconnectedness of things, the restoration of our place in the cosmos, and the embodied experience of womanhood. She showed it was possible to engage spiritual or ancestral knowledge and high-art intellectualism without seeming unserious, and her work continues to resonate with those who feel excluded from certain strains of Western rationalism.

“If you believe in Mother Nature,” Molesworth said, “if you believe in Mother Earth — no matter what your religious or spiritual affiliations are — if you have that kind of sense that nature is a fecund, gorgeous giver of life, then Mendieta’s work has some answers in it for us.”

She is far from the first to point this out. The podcast follows years of scholarship by and inspiration from other art historians — including Genevieve Hyacinthe’s 2019 book, Radical Virtuosity: Ana Mendieta and the Black Atlantic. Hyacinthe describes Mendieta’s work as a much-needed intervention into the Land Art movement, which is dominated by men who terraformed landscapes: “She was able to establish the awesomeness and the sublimity of monumental land works like Robert Smithson’s Spiral Jetty on a small and intimate scale.”

When Hyacinthe was working on her book, she felt that in order to understand it, she had to re-create it. So she and her assistant flew from New York to Mexico City, caught a connecting flight to Oaxaca, then drove a rental car to an archaeological site called Yagul. This 2,500-year-old settlement, home to now-empty ceremonial tombs, is where Mendieta created her first Silueta, Imagen de Yagul (Image of Yagul), in 1973: The photograph depicts the artist lying naked in a tomb, covered by bushels of tiny, white baby’s-breath flowers. When Hyacinthe and her assistant arrived, they asked the groundskeepers if they happened to know the spot where Mendieta took the photo. One worker remembered that other visitors had also come asking questions about a woman artist who had died — and when the attendants walked away, a nervous Hyacinthe quickly undressed and lay down in a tomb under a blanket of flowers.

So this is what Mendieta must have felt, she thought: the cold, damp ground, the irksomeness of bugs crawling around her, the struggle to hold her pose so that it matched what was in her mind’s eye. “I actually wanted it to be done very quickly,” Hyacinthe told me. If Mendieta was feeling any of those things, it doesn’t come across in the resulting photo. Its peaceful tenor suggests not death but the healing restoration of some long-lost life force.

Mendieta’s sustained popularity could be attributed as much to the profound yet approachable messages in her work as to its visual beauty. But it’s also easy to project on her the roles one may want her to take: an empowered Latina, a spiritual healer, a tragic victim of the patriarchy. “The biggest push-pull was how to tell the story respectfully,” said Molesworth, “how not to fall into either the angry or defensive postures, not to prejudge while still knowing one thought, and how to avoid treating the story like a spectacle. Even though, of course, it is a spectacular story.”