THE TREES OF GREAT BRITAIN & IRELAND - VOL. IV

THE TREES OF GREAT BRITAIN & IRELAND - VOL. IV

THE TREES OF GREAT BRITAIN & IRELAND - VOL. IV

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

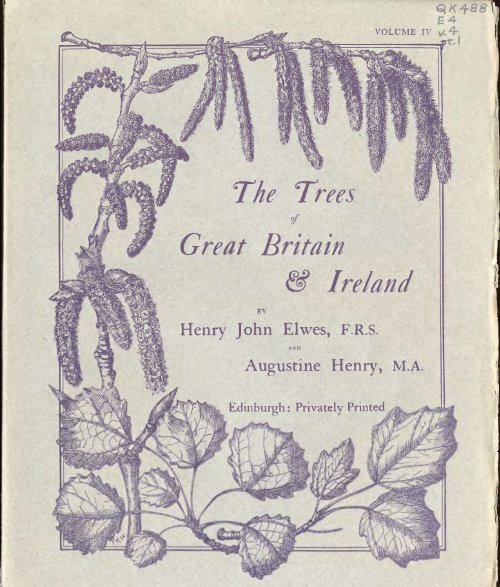

<strong>VOL</strong>UME <strong>IV</strong>The TreesofGreat BritainIrelandBYHenry John Elwes, F.R.S,ANDAugustine Henry, M.A.Edinburgh: Privately Printed*

<strong>THE</strong> <strong>TREES</strong> <strong>OF</strong> <strong>GREAT</strong> <strong>BRITAIN</strong> AND <strong>IRELAND</strong>

'.f

NAT<strong>IV</strong>K SCOTS PINF. AT INVERGARRVft cm a Drawing by Jlfiss Ruth Brand

MfM.4'*•»••fl*Great BritainIrelandBYHenry John Elwes, F.R.S.ANDAugustine Henry, M.A.<strong>VOL</strong>UME <strong>IV</strong>Edinburgh: Privately PrintedOyMCMIXw!k,|/ X'I,

CONTENTSLIST <strong>OF</strong> ILLUSTRATIONS ....ARIES ......ABIES PECTINATA, COMMON SILVER FIRABIES PINSAPO, SPANISH FIRABIES NUMIDICA, ALGERIAN FIRABIES CEPHAI.ONICA, GREEK FIRABIES CILICICA, CILICIAN FIRABIES NORDMANNIANA, CAUCASIAN FIRABIES WEBBIANA, HIMALAYAN FIR .ABIES PINDROW, PINDROW FIRABIES SIBIRICA, SIBERIAN FIRABIES SACHALINENSIS, SAGHALIEN FIRABIES FIRMA, JAPANESE FIRABIES HOMOLEPIS .....ABIES BRACHYPHYLLA, NlKKO FlR .ABIES UMBELLATA .....ABIES VEITCHII, VEITCH'S FIRABIES MARIESII, MARIES' FIRABIES GRANDIS, GIANT FIR ....AWES CONCOLOR, COLORADO FIRABIES LOWIANA, CALIFORNIAN FIR .ABIKS AMABILIS, LOVELY FIRABIES NOBILIS, NOBLE FIR ....ABIES MAGNIFICA, RED FIR, SHASTA FIRABIES BRACTEATA, BRISTLE-CONE FlRABIES LASIOCARPA, ROCKY MOUNTAIN FIR .ABIES BALSAMEA, BALSAM FIRABIES FRASERI, SOU<strong>THE</strong>RN BALSAM FIRABIES RELIGIOSA, MEXICAN FIRPSEUDOTSUGA .....PSEUDOTSUGA DOUGLASII, DOUGLAS FlRCASTANEA ......CASTANEA SAT<strong>IV</strong>A, SPANISH OR SWEET CHESTNUT .Hi71372073 273773974474675°755758760762764765768768771773777779782786792796800803806808811814837839^——————^ON1VE,LIERAR

The Trees of Great Britain and Ireland Contents VMCASTANEA CRENATA, JAPANESE CHESTNUTCASTANEA DENTATA, AMERICAN CHESTNUT .CASTANEA PUMILA, CHINQUAPINFRAXINUS ......FRAXINUS EXCELSIOR, COMMON ASHFRAXINUS ANGUSTIFOLIA, NARROW-LEAVED ASHFRAXINUS OXYCARPA ....FRAXINUS SYRIACA .....FRAXINUS ELONZA .....FRAXINUS WILLDENOWIANA ....FRAXINUS DIMORPHA ....FRAXINUS XANTHOXYLOIDES ....FRAXINUS POTAMOPHILA ....FRAXINUS RAIBOCARPA ....FRAXINUS HOLOTRICHA ....FRAXINUS ORNUS, FLOWERING ASH, MANNA ASH .FRAXINUS FLORIBUNDA ....FRAXINUS BUNGEANA ....FRAXINUS MARIESII .....FRAXINUS RHYNCHOPHYLLA ....FRAXINUS MANDSHURICA ....FRAXINUS CHINENSIS ....FRAXINUS OEOVATA ....FRAXINUS PUEINERVIS ....FRAXINUS SPAETHIANAFRAXINUS LONGICUSPIS ....FRAXINUS NIGRA, BLACK ASHFRAXINUS ANOMALA, UTAH ASHFRAXINUS QUADRANGULATA, BLUE ASHFRAXINUS AMERICANA, WHITE ASH .FRAXINUS TEXENSIS, TEXAN ASHFRAXINUS BILTMOREANA, BILTMORE ASHFRAXINUS LANCEOLATA, GREEN ASHFRAXINUS PENNSYLVANIA, RED ASHFRAXINUS OREGONA, OREGON ASH .FRAXINUS CAROLINIANA, SWAMP ASHFRAXINUS VELUTINAZELKOVA ......ZELKOVA CRENATA . . . ...ZELKOVA ACUMINATA ....8548568578598648?98828838838848848858858868878878908918928928938958958968978978989009009019 5906907908910912912914920CELTIS .....CELTIS AUSTRALIS, NETTLE TREE .CELTIS CAUCASICA ....CELTIS GLABRATA ....CELTIS DAVIDIANA ....CELTIS OCCIDENTALS, HACKP.ERRV .CELTIS CRASSIFOLIA, HACKBERRYCELTIS MISSISSIPPIENSISALNUS .....ALNUS GLUTINOSA, COMMON ALDERALNUS INCANA, GREY ALDERALNUS CORDATA, ITALIAN ALDERALNUS SUBCORDATA, CAUCASIAN ALDERALNUS FIRMA ....ALNUS JAPONICA, JAPANESE ALDER .ALNUS NITIDA, HIMALAYAN ALDER .ALNUS MARITIMA ....ALNUS RUERA, OREGON ALDERALNUS TENUIFOLIA ....ALNUS RHOMEIFOLIABETULA .....BETULA PUBESCENS, COMMON BIRCHBETULA VERRUCOSA, SILVER BIRCH .BETULA DAVURICA ....BETULA CORYLIFOLIABETULA MAXIMOWICZIIBETULA ERMANI ....BETULA ULMIFOLIA ....BETULA LUMINIFERABETULA UTILIS, HIMALAYAN BIRCH .BETULA pApyRiFERA, PAPER BIRCH, CANOE BIRCHBETULA POPULIFOLIA, GREY BIRCH .BETULA NIGRA, RED BIRCHBETULA LUTEA, YELLOW BIRCHBETULA LENTA, CHERRY BIRCH, BLACK BIRCHBETULA FONTINALIS ....DlOSPYROS .DlOSPYROS VIRGINIANA, AMERICAN PERSIMMONDIOSPYROS LOTUS, DATE-PLUM9 2 592692892992993°93293393593794594995195 295395495595 695795895996296697497597697797998098098398798899°991992995996999\C7

ILLUSTRATIONSNative Scots Pine at Invergarry (from a drawing by Miss Ruth Brand) . . FrontispiecePLATE No.Silver Fir at Cowdray ... ..... 208Silver Fir at Longleat . . . . . . . . .209Silver Fir at Roseneath . . . . . . . . .210Silver Fir at Tullymore . . . . . . . . .211Spanish Fir in Andalusia . . . . . . . . .212Spanish Fir at Longleat . . . . . . . . .213Greek Fir at Barton . . . . . . . . . .214Himalayan Fir in Sikkirn . . . . . . . . .215Japanese Fir in Japan . . . . . . . . .216Giant Fir at Eastnor Castle . . . . . . . . .217Giant Fir in Vancouver's Island . . . . . . . .218Californian Fir at Linton . . . . . . . .219Lovely Fir in British Columbia . . . . . . . .220Noble Fir in Oregon . . . . . . . . .221Red or Shasta Fir at Bayfordbury . . . . . . . .222Red or Shasta Fir at Bonskeid . . . . . . . .223Bristle-cone Fir at Eastnor Castle . . . . . . . .224Rocky Mountain Fir in Montana . . . . , . . .225Mexican Fir at Fola ......... 226Douglas Fir on Barkley's Farm . . . . . . .227Douglas Fir Forest in Vancouver's Island . . . . . . 228Douglas Fir at Eggesford . . . . . . . . .229Douglas Fir at Lynedoch . . . . . . . . .230Douglas Fir at Tortworth . . . . . . . . .231Spanish Chestnut Grove at Bicton . . . . . . . .232Spanish Chestnut at Althorp ......... 233Spanish Chestnut at Thoresby . . . . . . . 234Spanish Chestnut at Rydal . . . . . . . . 235Spanish Chestnut at Rossanagh . . . . . . . .236vii

Vlll The Trees of Great Britain and IrelandPLATE No.Japanese Chestnut at Atera, Japan .Weeping Ash at Elvaston CastleTall Ash at Cobham Park .Twisted Ash at Cobham ParkTall Ash at Ashridge .Ash at Woodstock, KilkennyAsh at Castlewellan .Diseased Ash at Colesborne ; Deformed Ash at CirencesterNarrow-leaved Ash at Rougham HallWhite Ash at Kew .Biltmore Ash at Fawley CourtZelkova crenata at Wardour Castle .Zelkova crenata at GlasnevinZelkova acuminata at CarlsruheCeltis occidentalis at West Dean ParkAlders at Lilford .Alders at Kilmacurragh .Italian Alder at Tottenham House, SavernakeBirch at Savernake Forest .Birch at Merton Hall .Birches in Sherwood Forest .Gnarled Birches in GlenmorePaper Birch at Bicton .Yellow Birch at Oriel TempleDiospyros virginiana at Kew . .Fraxinus; leaves, etc.Fraxinus; leaves, etc. .Fraxinus ; leaves, etc.Fraxinus; leaves, etc.Fraxinus; leaves, etc. .Moms, Celtis, and Zelkova; leaves, etc.Alnus.; leaves, etc. .Betula; leaves, etc. .Betula; leaves, etc. .2372 3 8239240241242243244245246247248249250251252253254255256257258259260261262263264265266267268269270fABIESA^ies, Linnaeus, Gen. PL 294 (in part) (1737); Bentham et Hooker, Gen. PI. iii. 441 (1880);Masters, Journ. Linn. Soc. (£ot.) xxx. 34 (1893); Hickel, Bull. Soc. Dendr. France, 1 907, pp.5, 41, and 82 ; 1908, pp. 5 and 179.Picea, D. Don, in Loudon, Arb. et Frut. Brit. iv. 2293 (1838).EVERGREEN trees belonging to the order Coniferae; bark containing numerous resinvesicles; branches whorled. Buds, with numerous imbricated scales, with or withoutresin, usually two to five at the ends of the branchlets, the central bud terminal andlargest, the others surrounding it in a circle on upright shoots, whilst on lateralbranchlets those on the upper side are not developed ; buds also occur rarely andfew in number in the axils of the leaves on the branchlets below. Branchlets of onekind, usually smooth, but in certain species grooved, with raised pulvini; eachseason's shoot * marked by a sheath at the base, composed of the persistent budscalesof the previous spring.Leaves on fertile and barren branchlets, often different in length and thicknessand in the nature of the apex ; arising from the branchlets in spiral order, radiallydisposed on vertical shoots, but variously arranged according to the species onlateral branchlets; persisting for many years and giving the tree a dense mass offoliage; leaving as they fall circular scars on the branchlets ; sessile, but usuallynarrowed just above the expanded circular base; linear, flattened and thin in mostspecies, quadrangular in section in a few species; ventral surface always with twogreyish or white stomatic bands, one on each side of the raised green midrib; dorsalsurface with or without stomata, which when present are either in continuous lines,as in the quadrangular-leaved species, or are confined to near the tip of the leaf inthe middle line, as in some flat-leaved species; apex acute, acuminate, or obtuse,notched or entire, spine-pointed in one or two species; resin-canals 2 two, constantin position for each species in the leaves on lateral branchlets, but in some species 3differing in position in the leaves on the upright or fertile branchlets, either median,1 In A . bracteata, all the bud-scales usually fall off, leaving ring-like scars at the base of the shoot.2 The position of the resin-canals is easily seen on examining a thin section with a lens ; and can often be made out bysqueezing the leaf, after it is cut across, when the resin will be observed exuding from the two canals.3 In A . pectinata, A. ccphalonica, and A . Nordmanniana, the resin-canals are marginal in the leaves of lateral branches,and are median in the leaves of cone-bearing branches. Cf. Guinier and Maire, in Bull. Soc. Bot, France, Iv. 189 (1908).<strong>IV</strong> 713 B

714 The Trees of Great Britain and Irelandwhen situated in the substance of the leaf about equidistant between its upper andlower surfaces, or marginal or sub-epidermal, when placed in the lower part of theleaf close to the epidermis; fibro-vascular bundle simple in some species, dividedinto two parts in other species.Flowers monoecious, the two sexes on separate branchlets; male flowers usuallyabundant and on the lower side of the branchlets over the upper half of the tree ;female cones on the upper side of the branchlets, usually only near the top of thetree, but in some species borne all over the upper half of the tree. Staminateflowers, 1 solitary in the axils of the leaves of the preceding year's shoot; stamensspirally crowded on a central axis, anthers surmounted by a knob-like projectionand dehiscing transversely. Female cones, 1 arising as short shoots, composed ofnumerous imbricated fan-shaped ovuliferous scales, and an equal number of muchlonger mucronate bracts ; ovules inverted, two on each scale.Mature cones erect on the branchlets, composed of closely imbricated woodyscales, more or less fan-shaped with short stalks. Bracts adnate to the outer surfaceof the scales at the base ; either concealed between the scales or with their tipsexserted and then often reflexed over the margin of the scale next below ; dilated atthe apex, entire or two-lobed, prolonged into a triangular mucro. Seeds two on theinner surface of each scale, winged, and with resin-vesicles. The cones ripen in oneseason ; and the scales, bracts, and seeds fall away from the central spindle-like axisof the cone, which persists for a long time on the tree. The seedling has four to tencotyledons, stomatiferous on their upper surface.The species of Abies are distinguishable from all other conifers by the circularbase of the leaves, which on falling leave circular scars on the branchlets.The species of Abies have been variously divided into sections by differentauthors, but no satisfactory arrangement has yet been made out. Mayr proposedthree sections based on the colour of the cones ; but, as Sargent 2 points out, colouris not a constant character in several species. The cones are of value in the discrimination of the species, by taking into account their age, general appearance, andcharacters as a whole ; but the scales are often very variable in shape in the samespecies, and the bracts, while more constant in form, often show considerablevariation in their length. It is most convenient, in practice, especially as cones arein most cases not available for examination, to group the species, according to thecharacters of the buds, branchlets, and foliage, which are, as a rule, very constant inthe same species. Hickel 3 proposes three sections, based on the characters of thebranchlets and buds; but his division is artificial, as it separates species closelyallied by the characters of their cones.Some notes on the genus Abies, for which we are indebted to Mr. J. D.Crozier, forester to H. R. Baird, Esq. of Durris, Kincardineshire, are inserted.Mr. Crozier's long experience in the east of Scotland gives a special value to hisopinion on their respective qualities for planting in Scotland, which our own1 Both the Staminate flowers and the young female cones are surrounded at the base by involucres of bud-scales.2 Sitva N. Amer. xii. 97, adnot. ( 1898). Sargent proposes three sections, based on the characters of the leaves.3 Bull. Soc. Dendr. France, 1 907, p. II.Abies 715could not have, though in almost every case he confirms the conclusions at whichwe had already arrived.About thirty species are known, of which twenty-six have been introduced andare distinguished below. The silver firs are natives of the temperate parts of thenorthern hemisphere, usually occurring in mountainous regions; attaining highelevations towards the south, as in Guatemala, Algeria, Himalayas, and Formosa;and descending to low levels in the extreme north, as Alaska, Labrador, and Siberia.The following table is based upon characters taken from the foliage, buds, andshoots of lateral branches, occurring on the lower part of the tree. As regards theleaves, their arrangement upon the branchlets, the position of the resin-canals, andwhether the apex is entire or bifid must be noted. The presence of stomata on theupper surface of the leaf is peculiar to certain species. The young shoots are eithersmooth or deeply grooved with prominent pulvini; and are glabrous in some species,pubescent in others, the pubescence when present being either confined to thegrooves or spread over the whole branchlet. The buds vary in size and shape andalso in the quantity of resin, which in some cases is so slight that they may bedescribed as non-resinous ; whilst in other species the scales are covered with ordeeply immersed in resin.Certain species are distinguishable at a glance by some prominent character.A. bracteata has a bud entirely different from that of any other species. A . Pinsapo,with its short, thick, rigid leaves, standing out radially from the shoot, is unmistakable. A . cephalonica, with a more imperfect radial arrangement, is distinguishedby its long flattened leaves ending in a single sharp cartilaginous point. A . firma ispeculiar in its remarkably broad very coriaceous leaves, which end in two sharpunequal points. A . grandis has the leaves quite pectinate in the horizontal plane,those of the upper rank about half the size of those below. A. Mariesii is distinguished by the shoot being densely covered with a ferruginous tomentum. A .brachyphylla and A . Webbiana have deeply-furrowed shoots with prominent pulvini,which become more marked in the second year; and the bark begins to scalevery early on the branches and trunk of the tree. A . nobilis and A . magnifiedare peculiar in the upper median leaves curving up from the shoot after beingappressed to it for some distance. A . Pindrow has long pale green leaves veryirregularly arranged.I. Leaves radially arranged on the branchlets ; apex of the leaf not bifid.1. Abies Pinsapo, Boissier. Spain. See p. 732.Leaves rigid, short, less than f inch long, thick, acute at the apex ; resincanalsmedian. Shoots glabrous. Buds resinous.2. Abies cephalonica, Loudon. Greece. See p. 739.Leaves thin, flattened, about i inch long, ending in a sharp cartilaginouspoint; resin-canals marginal. Shoots glabrous. Buds resinous.In van Apollinis, the radial arrangement is imperfect, and the leaves end ina short point.

716 The Trees of Great Britain and IrelandII. Leaves on the lateral branches pectinate in arrangement; the t^vo lateral setseither in one plane, or with their upper ranks directed upwards as wellas outwards, showing a V-shaped depression, as seen from above, between thetwo sets.* Resin-canals marginal?3. Abies bracteata, N uttall. California. See p. 796.Leaves long, 2 inches or more, rigid, ending in a spine-like point. Shootsglabrous. Buds peculiar in the genus, elongated, fusiform, membranous,non-resinous.4. Abies grandis, Lindley. Western N. America. See p. 773.Leaves all in one plane, those in the upper rank about half the lengthof those below, up to 2 inches long, bifid at the apex; upper surfacegrooved and without stomata. Shoots minutely pubescent. Buds small,resinous.5. Abies Lowiana, Murray. California. See p. 779.Leaves in a V-shaped arrangement, IJ to 2^ inches long, bifid at the apex ;upper surface grooved and with eight lines of stomata. Shoots and budsas in A . grandis.6. Abies firma, S iebold and Zuccarini. Japan. See p. 762.Leaves in a V-shaped arrangement, rigid, very coriaceous, broad, up to \\ inchlong, ending in two sharp cartilaginous points. Shoots pubescent in thefurrows between the slightly raised pulvini. Buds small, ovoid, onlyslightly resinous.7. Abies homolepis, Siebold and Zuccarini. Japan. See p. 764-Leaves in arrangement and appearance like A . firma ; but shorter, lesscoriaceous, narrower, and whiter beneath. Shoots with prominent pulvini,glabrous. Buds ovoid, resinous, larger than in A . firma.8. Abiespectinata, De Candolle. Europe. See p. 720.Leaves pectinate in one plane or tending to a V-shaped arrangement, aboutan inch long, slightly bifid at the apex. Shoot grey, with short pubescence.Buds ovoid, non-resinous.9. Abies Webbiana, Lindley. Himalayas. See p. 750.Leaves V-shaped in arrangement, up to 2^ inches long, bifid, silvery whitebeneath. Shoots with prominent pulvini and deep grooves, with a reddishpubescence confined to the grooves. Buds large, globose, resinous.** Resin-canals median?10. Abies balsamea, M iller. Eastern N. America. See p. 803.Leaves slender, scarcely i inch long, bifid at the apex, with six to eight linesof stomata in each band on the lower surface. Shoots, smooth, grey, withscattered short erect grey pubescence. Buds globose, resinous.11. Abies Fraseri, Poiret. Alleghany Mountains. See p. 806.Leaves as in A . balsamea, but shorter and whiter beneath, with eight to1 A. cilicica and A. numidica, with weak shoots, come in this section. See Nos. 22 and 23.2 Abies lasiocarfa, Nuttall, often has the leaves more or less pectinate, and might be sought for here. See No. 26.Abies 717twelve lines of stomata in each band beneath. Shoots smooth, yellowish,with dense reddish curved or twisted pubescence. Buds globose,resinous.12. Abies brachyphylla, Maximowicz. 1 Japan. Seep. 765.Leaves in a V-shaped arrangement, short, scarcely exceeding f inch, slightlybifid, white beneath. Shoots glabrous, with prominent pulvini and deepgrooves. Buds conical, resinous.III. Leaves on lateral branches not pectinate above, but densely crowded, those in themiddle hne directed forwards in imbricated ranks, their bases not beingappressed to the branchlet. On the lower side of the shoot the leaves are intwo lateral sets.* Resin-canals marginal?13. Abies Nordmanniana, Spach. 3 Caucasus, Northern Asia Minor. See p. 746.Leaves up to \\ inch long, with rounded bifid apex. Shoots smooth, withshort scattered erect pubescence. Buds ovoid, brown, non-resinous.14. Abies amabilis, Forbes. Western N. America. See p. 782.Leaves in arrangement and size like those of A . Nordmanniana, but muchdarker shining green, and with a truncate bifid apex ; they emit a fragrantodour when bruised. Shoots smooth, with short wavy pubescence. Budssmall, globose, resinous.15. Abies religiosa, Schlechtendal. Mexico, Guatemala. See p. 808.Leaves about i inch long, gradually narrowing from the middle to theusually entire apex, which is occasionally slightly emarginate. Shootswith prominent pulvini and dense minute erect pubescence. Buds shortlycylindrical, resinous.The median upper leaves are much less numerous than in the two precedingspecies.16. Abies Mariesii, Masters. Japan, Formosa. See p. 771.Leaves shorter and broader than in Abies Veitchii, widest in their upperthird, with a rounded and bifid apex. Shoot densely covered with aferruginous tomentum. Buds small, globose, resinous.** Resin-canals median.17. A bies Veitchii, Lindley. Japan. Seep. 768.Leaves up to i inch long, truncate and bifid at the apex, uniform in width,very white beneath, with nine to ten lines of stomata in each band. Shootssmooth, covered with dense short erect pubescence. Buds small, globose,resinous.The upper median leaves, pointing forwards, stand off from the shoot at awider angle than in A . Nordmanniana.1 Abies umbellata, Mayr, is said to be very similar in foliage to this species. See the description of this species, p. 768.2 A. numidica with strong shoots, is distinguished from all these species by the leaves of the upper side being directedbackwards. See No. 23.3 A. cilicica, with strong shoots, resembles a weak A. Nordmanniana. See No. 22.

718 The Trees of Great Britain and Ireland18. Abies sachalinensis, Masters. Saghalien, Yezo, Kurile Isles. See p. 760.Leaves long and slender, up to if inch, uniform in width, with a rounded andbifid apex, white beneath, seven to eight lines in each stomatic band.Shoots with prominent pulvini, and a dense short pubescence confined tothe grooves. Buds small, globose, resinous.19. Abies sibirica, Ledebour. N. E. Russia, Siberia, Turkestan. See p. 758.Leaves long and slender, up to i J inch, uniform in width ; apex rounded andeither slightly bifid or entire; four to five lines in each stomatic bandbeneath. Shoots ashy grey, quite smooth, with a scattered minutepubescence. Buds small, globose, resinous.<strong>IV</strong>. Leaves on lateral branches not pectinate above; those in the middle linecovering the branchlet, and curving Jtpwards after being appressed to theshoot for some distance at their base. The leaves are in two lateral sets onthe lower side of the branchlet. Resin-canals marginal.20. Abies nobilis, Lindley. Washington, Oregon, California. See p. 786.Leaves above closely appressed by their bases to the branchlet, which theycompletely conceal; about i inch long, entire at the apex, flattened, groovedon the upper surface in the middle line; stomata usually present on bothsurfaces. Shoots with a dense, short brown pubescence. Terminal budsgirt at the base by a ring of acute or subulately-pointed pubescent scales.21. Abies magnijica, Murray. Oregon, California. Seep. 792.Leaves above appressed at their bases, for a short distance only, to thebranchlet, which they do not completely conceal; longer than in A. nobilis,up to if inch, entire at the apex, quadrangular in section, not grooved onthe upper surface; stomata always present on both surfaces. Shoots andbuds as in A. nobilis.V. Leaves on lateral branches arranged in two ways, which are often observable onthe same tree, and depend ^^pon the vigour of the shoots.22. A bies cilicica, Carriere. Asia Minor. See p. 744.Leaves either (A) pectinate above with a V-shaped depression between thelateral sets, or (B) with the median leaves above crowded and covering thebranchlet, as in A . Nordmanniana. The leaves are slender, up to \\ inchlong, not conspicuously white below, slightly bifid at the rounded or acuteapex; resin-canals marginal. Shoots smooth, with scattered short erectpubescence. Buds small, ovoid, non-resinous.Vigorous shoots of this species resemble a weak A . Nordmanniana ; but withthe leaves shorter, more slender, and less white beneath, the buds beingmuch smaller.23. A . numidica, De Lannoy. Algeria. See p. 737.Leaves either (A) pectinate above with a V-shaped depression; or (B)crowded and covering the upper side of the branchlet, but different fromAbies 719all other species in the median leaves above, in that case, being directedbackwards and not forwards. Leaves short, up to f inch long, broad,rounded at the entire or slightly bifid apex ; in most cases with four to sixbroken lines of stomata on their upper surface near the tip; resin-canalsmarginal. Shoots brown, shining, glabrous. Buds large, ovoid, nonresmous.VI. Leaves irregularly arranged; those on the lower side of the branches not trulypectinate.24. Abies Pindroiv, Spach. W. Himalayas. See p. 755.Leaves all directed more or less forwards ; those above irregularly and imperfectly covering the branchlet; those below mostly pectinate, but with somedirected downwards and forwards. Leaves soft, pale green, up to z\ incheslong, bifid at the apex with two sharp cartilaginous points; resin-canalsmarginal. Shoots grey, glabrous. Buds large, globose, resinous.25. A bies concolor, Lindley and Gordon. Colorado, Utah, Arizona, New Mexico,Northern Mexico, Southern California. See p. 777.Leaves imperfectly pectinate both above and below, some in the middle linebeing always directed forwards and not laterally outwards; up to 2 to 3inches long; apex entire; upper surface convex and not grooved, bearingfifteen to sixteen lines of stomata ; resin-canals marginal. Shoots smooth,olive-green, glabrous. Bud large, conical, resinous.26. Abies lasiocarpa, N uttall. Western N. America. See p. 800.Leaves either (A) in an imperfect pectinate arrangement, or (B) with most ofthe leaves directed upwards, those in the middle line above crowded, andstanding edgeways; i^ inches long, narrow, usually entire, with conspicuous lines of stomata on the upper surface, especially in its anteriorhalf. Resin-canals median. Shoots smooth, with a moderately dense,short wavy pubescence. Buds small, conical, resinous.Four species, A . Delavayi, Franchet j 1 A . Fargesii, Franchet; 2 A . squamata,Masters; 8 and A. recurvata, Masters; * occur in the mountains of western Chinaand are not included in the above list. The two first species are reported byMasters to have been introduced by Wilson ; but, on inquiry, we find that only onespecies of Abies from China is now growing in the Coombe Wood nursery. It isprobably A . Fargesii; but, as the plants are still very young, we are uncertain ofthis identification, and think it best to leave this species undescribed for the present.(A. H.)^ Journ. dc Bot. 1 899, p. 255; Masters, Card. Chron. xxxix. 212, fig. 82(1906).2 Journ. dt Bot. 1 899, p. 256 ; Masters, Card. Chron. xxxix. 212, fig. 83 (1906).3 Card. Chron. xxxix. 299, fig. 121 (1906), and Journ. Linn. Soc. (Bot.), xxxvii. 423 (1906).4 Journ. Linn. Soc. (Bot.), x xxvii. 423 (1906).

72,0 The Trees of Great Britain and IrelandABIES PECTIN AT A, COMMON SILVER FIRAbiespectinala, De Candolle, in Lamarck, More Franf. iii. 276 (1805); Willkomm, Forstliche Flora,112 (1887); Mathieu, Flore Forestiere, 5 25 (1897) ; Kent, Veitch's Man. Coniferce, 530 (1900).Abies alba, 1 Miller, Diet. ed. 8, No. i (1768); Kirchner, Lebengesch. Bliitenpfl. Mittekuropas, i. 78(1904).Abies vulgaris, Poiret, in Lamarck, Diet. vi. 514 (1804).Abies Picea, Lindley, Penny Cycl. i. 29 (not Miller) (1833).Pinus Picea, Linnaeus, Sf. PI. 1 001 (1753).Pinns Abies, Du Roi, Obs. Bot. 3 9 (1771).Pinuspectinata, Lamarck, Fl. Franc, ii. 202 (1778).Picea pectinata, Loudon, Arb. et Frut. Brit. iv. 2329 (1838).A tree attaining under favourable conditions about 150 feet in height and 20feet or more in girth. Bark on young trees, smooth, greyish; ultimately fissuringand becoming rough and scaly. Buds small, ovoid, non-resinous; scales few,brownish, rounded at the apex. Young shoots grey, smooth, with a scattered shorterect pubescence, which is retained in the second year.Leaves on lateral branches pectinately arranged in two lateral sets; those belowthe longest and directed outwards and slightly forwards in the horizontal plane;those above directed upwards and outwards, forming between the two sets a shallowV-shaped depression. Leaves about i inch long, -fa inch broad, linear, flattened,narrowed at the base, tapering slightly to the rounded, bifid apex; upper surfacedark green, shining, with a continuous median groove and without stomata; lowersurface with two white bands of stomata, each of seven to eight lines; resin-canalsmarginal.On leading shoots the leaves are radially arranged, and differ considerably fromthose on lateral branches; they are thicker, with median resin-canals, acute and notbifid at the apex, and often show lines of stomata on their upper surface towards thetip. Leaves on cone-bearing branches are nearly all directed upwards, very sharppointed,and almost tetragonal in section.Trees, standing in an isolated position, usually begin to flower at about thirtyyears old; when crowded in dense forests, much later, usually not before sixtyyears old.Staminate flowers, surrounded at the base by numerous imbricated scales,cylindrical, about i inch long, with greenish - yellow stamens. Female cones,appearing in August of the previous year as large rounded buds, enclosed in brownscales, and situated just behind the apex of the shoot; in spring, when developed,erect, cone-shaped, about i inch long, surrounded at the base by fringed scales ;bracts numerous, imbricated, denticulate, ending in long, acuminate points, andcompletely concealing the much smaller ovate, rounded ovuliferous scales.1 Abies alba, the oldest name under the correct genus, was never in use until lately, when it has been resuscitated bySargent and some continental botanists. This is one of the cases where adhesion to strict priority would lead to great confusion ; and hence we have adopted the name Abies pectinata, by which the tree is generally known.Abies 72,1Cones on short stout stalks, cylindrical, slightly narrowed at both ends, obtuseat the apex, about 6 inches long, 2 inches in diameter, greenish when growing, dullbrown when mature, with the points of the bracts exserted and reflexed. Scalestomentose externally, fan - shaped, about i inch broad and long; upper marginslightly uneven; lateral margins denticulate, each usually with a sinus, below theslight wings on the outer side of the scale; claw clavate. Bract with an oblongclaw, extending up three-quarters the height of the scale, and expanding above intoa lozenge-shaped denticulate lamina, which ends in a sharp long triangular mucro.Seed with wing about an inch long; wing about twice as long as the body of theseed.SEEDLINGSeed sown in spring germinates in three or four weeks. The cotyledons,usually five in number, are at first enveloped, as with a cap, by the albumen of theseed ; but speedily casting this off, they spread radially in a whorl at the summit ofthe short caulicle, and remain green on the plant for several years; about an inch inlength, linear, obtuse at the apex, flat beneath, and slightly ridged on the uppersurface, which shows two whitish bands of stomata. In the first year only a singlewhorl of true leaves, arising immediately above the cotyledons and alternating withthem, is produced. Primary leaves short, acute, or obtuse, but not emarginate atthe apex, and with the stomatic bands on the lower surface. A terminal bud closesthe first season's growth, the plant scarcely attaining two inches high. In the secondyear ordinary leaves, arranged spirally on the stem, are produced. The growth ofthe plant in the first two or three years is mainly concentrated in the root, whichdescends deep into the soil, the increase in height of the stem above ground beingtrifling. The stem branches in the third or fourth year, and produces annually forsome years one or two lateral branches, making no great growth in height, reachingin the ninth year an average of two feet. About the tenth year normal verticillatebranching begins; and from this onwards the plant makes rapid growth.VARIETIESDr. Klein gives in Vegetationsbilder illustrations of some remarkable forms 1which the silver fir assumes at high elevations in Central Europe, and which he calls" Wettertanne " or " Schirmtanne." These trees have lost their main leader throughlightning, wind, or otherwise, and have developed immense side branches whichspread and then ascend, sometimes forming a candelabra-like shape. The finest ofthis type known to him is at St. Cerques in Switzerland, and measures at breastheight no less than 7.40 metres in girth, about the same as the largest of theRoseneath 2 trees.Other varieties, distinguished by their peculiar habit, occur in the wild state.1 These forms are also described by Dr. Christ in Garden and Forest, ix. 273 (1896).8 One of the trees at Roseneath, Dumbartonshire, has a similar growth of erect branches, like leaders from some of thehorizontal liinbs. This is figured, from a photograph by Vernon Heath, in Card. Chron. xxii. 8, fig. I (1884). At Powerscourtthere is also a large tree, 13 feet 3 inches in girth, with branches prostrate on the ground and sending up several uprightstems.<strong>IV</strong> c

72,2, The Trees of Great Britain and IrelandVar. pendula? with weeping branches, has been found in the Vosges and inEast Friesland.Var. virgata? found in Alsace and Bohemia, has long pendulous branches, onlygiving off branchlets near their apices, and densely covered with leaves.Var. pyramidalis? This form, which in habit resembles the cypress or aLombardy poplar, was found growing wild in the department of Isere in France. Avery fine example, about 35 feet high in 1904, is growing in the arboretum ofSegrez.Var. columnaris? very slender in habit, with numerous short branches, all ofequal length, and with leaves shorter and broader than in the type.Var. tortiiosa, a dwarf form, with twisted branches, and bent, irregularly-arrangedleaves.Var. brevifolia, another dwarf form, distinguished by its short broad leaves.Remarkable variations in the cones have also been observed. A tree, discoveredby Purkyne 5 in Bohemia, bore cones, umbonate at the apex, and with short and nonreflexedbracts. Beissner 6 mentions a tree, growing in the park at Worlitz nearDessau, which produced cones a foot in length.DISTRIBUTIONThe common silver fir is a native of the mountainous regions of central andsouthern Europe. The northern limit of its area of distribution begins in thewestern Pyrenees about lat. 43 in the neighbourhood of Roncesvalles in Navarre;and crossing the chain it extends along its northern slope as far as St. Beat; fromhere it bends northwards to the mountains of Auvergne, whence it is continued in anorth-easterly direction through Burgundy and French Lorraine, crossing the easternslope of the Vosges about the latitude of Strasburg. From here it curves for somedistance westward, and reaching Luxemburg, is continued through Trier and Bonnto southern Westphalia. Across the rest of Germany, according to Drude, whogives a map of the distribution of the species, the northern limit extends as anirregular line about lat. 51 , which touches Hersfeld, Eisenach, the northern edge ofthe Thuringian forest, Glauchau, Rochlitz, Dresden, Bautzen, and Gb'rlitz; and endsin the southern point of the province of Posen. Around Spremberg to the northof the limit just traced, it is found wild in a small isolated territory.The eastern limit, beginning in Posen, extends through Poland along the RiverWartha to Kolo, crosses to Warsaw, and descending through Galicia west ofLemberg, reaches the Carpathians in Bukowina; and is continued along themountains of Transylvania to Orsova on the Danube.The southern limit is not clearly known as regards the Balkan peninsula, asthe silver fir, which occurs in the mountains of Roumelia, Macedonia, and Thrace,1 Kottmeier found peculiar weeping silver firs in the Friedeberg forest, near Wittmund in East Friesland, in 1882.Cf. Wittmack's Garlenzeitung, 1 882, p. 406, and Conwentz, Seltene Waldbdume in Westfreussen, 1 61 (1895).2 Caspary, in IlempeFs Oesterr. Forstzeitung, 1 883, p. 43.3 Carriere, Conif. 280. 4 Carriere, Rev. Hort. 1 859, p. 39.6 Willkomm, Forstliche Flora, 1 18 (1887). 8 Nadelhohkunde, 433 (1891).Abies 7*3supposed to be A . pectinata, is more probably a form of A . Apollinis. In Italy thecommon silver fir reaches its most southerly point on the Nebroden and MadoniaMountains of Sicily at lat. 38 . From here the limit follows the Apennines upthrough Italy, crosses into Corsica, and from there passes into Spain, where itextends from Monseny, near the Mediterranean coast in lat. 41 25', parallel to thePyrenees, through the mountains of Catalonia and northern Aragon to Navarre.In Spain the silver fir also occurs westwards on a few points of the northern littoralin the Basque provinces and Asturias.Within the extensive territory just delimited, the silver fir is very irregularlydistributed, being totally absent in many parts, as on the plains and lower mountainsof southern Europe. In the eastern part of its area it occurs only as isolated treesor in small groups in the beech and spruce forests; whereas, in the western part, asin France and in parts of Germany, it forms forests of great extent, either pure or inwhich it is the dominant species.In France the largest forests of the silver fir are in the Vosges and in the Jura.Important forests also occur in the eastern parts of the Pyrenees, the Cevennes, themountains of Auvergne, and the Alps of Dauphine. It is rare on the hills ofBurgundy, and does not occur in the Ardennes. There are small woods of thisspecies on some of the hills in Normandy, which are, however, supposed to beplanted and not indigenous. The great forest of the Vosges* is about 50 miles longby 5 to i o miles in width, and contains about 200,000 acres, situated mainly between1100 and 3300 feet elevation. This forest consists chiefly of silver fir, though, insome parts, there is a considerable mixture of beech, spruce, and common pine.The most productive woods are on siliceous soil, and only contain 10 per cent ofbeech and pine; their mean annual production being about 100 cubic feet per acre,the volume of timber standing on each acre averaging 4500 cubic feet.In the Jura there are even richer and more homogeneous forests than in theVosges, being according to Huffel the finest in Europe. Here the soil is limestone.One of these forests, which covers Mount La Joux, between 2100 and 3000 feetaltitude, contains 10,600 acres, and consists of about 90 per cent silver fir and 10 percent of spruce. The annual yield per acre is 170 cubic feet of timber. The totalvolume of standing timber, including only trees over 2 feet in girth, is 6000 cubicfeet per acre. The net revenue is thirty-two shillings an acre. There are severalother forests equally valuable in this region.One of the finest silver firs 1 in France, a tree called " Le President," is growingin the forest of La Joux. It is 163 feet high, with a clean stem of 93 feet, and a girthof 15 feet; and contains 1600 cubic feet of timber. In the forest 2 of Gerardmer,in the Vosges, there are two fine trees. One, the Beau Sapin, has a height of144 feet and a girth of 13 feet 8 inches; it contains 777 cubic feet of timber, and isvalued at ^16. The other, the Gdant Sapin, has a height of 157 feet and a girthof 14 feet 5 inches; it contains 1095 cubic feet of timber, and is valued at ,£27. Inthe Pyrenees the silver fir occurs between 4500 and 6500 feet elevation, and trees1 See Huffel, Economic Forestiire, i, 349, 350, 353 (1904).2 Cf. Trans. A Scot. Arh. Soc. xviii. 131 (1905).

724 The Trees of Great Britain and Irelandof great age, about 800 years old, are said* to have existed there at the beginning ofthe i gth century.In Corsica the silver fir occurs in the great forests of Pinus Laricio, butis not abundant, as it only grows, as a rule, in scattered groups in the gullies,where the soil is deeper and richer than elsewhere; and at Valdoniello I onlysaw a few trees, none of which were of large size. M. Rotges, of the ForestService, informed me that it occurs in greatest quantity in the forest of Pietropiano,near Corte.In Italy the silver fir is unquestionably wild on the Apennines, and considerableforests exist at Vallombrosa and Camaldoli, which are now owned by the government. That at Camaldoli is particularly fine, the total area covered by the silverfir being about 1600 acres. The trees are dense on the ground and very vigorousin growth; and this is easily explained by the heavy rainfall, which, as measured atSt Eremo, in the middle of the forest, at 3600 feet altitude, averages about 80inches annually. I saw, when I visited Camaldoli, in December 1906, no treesof great size ; but one was cut down in 1884, and a log of it shown at the NationalExhibition at Turin in that year, which measured 140 feet in height and 17 feet ingirth.The silver fir also occurs in Sicily in small quantity, on the higher mountains,and specimens without cones, which I saw in the museum at Florence, are peculiarin the foliage, and form possibly a connecting link between A . pectinata and A .numidica.In Germany, towards the northern part of its area of distribution, the silver firis met with growing wild on the plains, as in Saxony, Silesia, and Thuringia.Towards the south it is entirely a tree of the mountains, occupying a definite zone ofaltitude, which, in the Bavarian forest, lies between 950 and 400x3 feet. The largestforests, which are nearly pure, occur in the Black Forest and in Franconia; those inBavaria, Bohemia, Thuringia, and Saxony being smaller in extent.In Switzerland small forests occur at Zurich, Payerne, and on Mount Torat;the silver fir ascending in the Swiss Alps to 530x3 feet altitude. (A. H.)As to the size 2 which the silver fir attains in its native forests, many particularsare given by French and German foresters, some of which have been quoted above.None exceed, however, what I have seen in the virgin forests of Bosnia, where Imeasured near Han Semec, at an elevation of about 3000 feet, a fallen tree over 180feet long, whose decayed top must have been at least 15 to 20 feet more. Loudonstates that he saw, in the museum at Strasburg, a section of a tree of the estimatedage of 360 years, cut in 1816 at Barr, in the Hochwald, which was 8 feet in diameterat the base and 150 feet high.The virgin forests of Silesia and Bohemia contain silver firs of immense size,of which very interesting particulars are given by Gb'ppert,3 who states that, inPrince Schwarzenberg's forest of Krummau, there existed many silver firs of from1 Willkomm, Forstliche Flora, 1 16, note (1887).2 Kerner, Nat. Hist. Plants, Eng. trans. i. 722, gives the " certified height" of Abies pectinata as 75 metres, or 250feet; but this is not confirmed hy other authorities.3 H. R. Goppert, Skizzen zur Kenntniss der Urwalder Schlesiens und Bohmens, 1 8 (1868).rPAbies 7*5120 to 200 feet high, free from branches up to 80 to 120 feet, and as muchas 6 to 8 feet in diameter. He quotes Hochstetter, 1 who measured in theGreinerwald, near Unter-Waldau, at an elevation of 2563 feet, a silver fir blowndown by a storm, which was 9^- feet in diameter at breast height and 200 feet long,and produced 30 klafter of firewood.The silver fir is planted outside the area of its natural distribution in most partsof France, in Belgium, and in western and northern Germany, but not beyond lat.51 in eastern Prussia. It is occasionally planted in Norway, and at Christianahas attained 68 feet in length by 3^ feet in girth. At Thlebjergene, near Trondhjem,where, on the side of a hill, sloping down to the sea, with an easterly exposure,a fine plantation, 2 mainly of spruce and Scots pine, was made in 1872 and subsequentyears, there are some splendid groups of silver fir, 30 to 40 feet in height, apparently exceeding in rapidity of growth the native spruce beside it. It is met with ingardens in the Baltic provinces of Russia, as in Lithuania where there is a smallwood near Grodno, and in Courland and Livonia; here, however, it always remainsa small tree, never bears cones, and is much injured by severe winters.One of the most remarkable plantations in Europe is the one made by theHanoverian Oberforster, J. G. von Langen, in the Royal Park of Jaegersborg, nearCopenhagen, about 1765. I visited this place in 1908, and measured some of thetrees. I found that the largest now standing near the entrance at Klampenborgwas 125 feet by 12 feet 10 inches. This tree is figured in a work 8 kindly sent meby Skovrider H. Mundt. There are, however, many taller trees on the southside of the main drive, two of which I found to be 140 feet by 9 feet, and 140 feetby 8 feet in girth, respectively. I measured the girth of twenty trees out of sixtytwowhich are growing on an area of 100 by 30 paces, and believe them toaverage over 130 feet high, with an average girth of 7^ feet. In Lutken's work fulldetails are given of the measurements of these trees taken in 1893, and confirmedin 1898 by Oppermann, who found 432 trees, averaging 38-9 metres in height andcontaining 1400 cubic metres per hectare; which is equal to 20,0x30 cubic feet peracre in the round, or 15,700 feet English quarter-girth measure. My own hastyestimate on the spot was about 12,000 feet English quarter-girth measure per acre.These wonderful silver firs grow on a deep, sandy loam, on level ground near thesea, and seem to have passed their prime. Some of their timber has been used asrafters in the Secretariat hall of the new Raadhus at Copenhagen.A.pectinata* was brought to the eastern United States early in the nineteenthcentury; but it is not hardy even in the middle states.Witches' brooms and cankered swellings, due to the fungus ^Ecidiumelatinum, De Bary, are common on the silver fir in the continental forests; andare often seen in Ireland and the south-west of Scotland, 5 though apparently rarein England, where they have been noticed in Norfolk 6 and at Haslemere. 71 Hochstetter, Aits dan Bohmerwalde, Allg. Augsb. Zeit. 1 855, N - l g2- Cf- Sendtner, Die Vegetations-Verhaltnissedes Bayerischen Waldes ( 1860). 3 Lutken, Den Langenske Forstordning, p. 286, fig. 5 (Copenhagen, 1899).2 Seen by Henry in 1908.4 Sargent, Silva N. Amer. xii. 100, adnot. ( 1898). 6 Somerville, in Hartig, Diseases of Trees, Eng. trans. 179 (1894).8 Trans. Norfolk and Norwich Naturalist? Soc. vii. p. 255. i Specimens at Kew.

72,6 The Trees of Great Britain and IrelandThe swellings which affect the trunk or branches are due to the irritation ofthe fungus mycelium, which is perennial and stimulates the wood and bark toabnormal growth. These swellings become fissured and are entered by thespores of other fungi, which rot the wood ; and the tree, if the stem is affected,is often broken off at the weakened spot by storms or falls of snow. Thewitches' brooms begin as young shoots, bearing small yellowish leaves, on theunder surface of which two rows of tecidia are developed in August. Theseshed their spores at the end of that month and the leaves soon afterwards die andfall off. The affected shoots keep on growing, and develop into peculiar growths,set upright generally on the branches, and consisting of numerous twigs anastomosedtogether. The fungus passes one stage of its life on various species of Stellaria,Cerastium, and their allies, and Fischer 1 recommends the extirpation of these plantsfrom nurseries in which the silver fir is raised.The silver fir is very liable in its native forests to be attacked by the mistletoe.Modified roots, the so-called sinkers of the parasite, have been found in the woodenclosed in forty annual rings and as much as 4 inches long, showing that mistletoemay live on the tree for forty years. When the mistletoe dies the rootlets andsinkers survive for a time, but finally moulder and fall to pieces. The affected partsof the wood show numerous perforations, and exactly resemble the wood of atarget that has been penetrated by shot or small bullets."The bark of the silver fir remains alive on the surface to an advanced age; and,on this account, when branches, stems, or roots of adjoining trees get into contact,they often become grafted together. This is the explanation of the curiousphenomenon of the vitality of the stumps of certain trees in forests. After thestem is cut down, these stumps continue to increase in size and produce a callosity,which eventually covers the stump in the form of a hemispherical cap. Such astump procures its nourishment from an adjoining tree, with which its roots havebecome grafted.8CULT<strong>IV</strong>ATIONThe silver fir 4 was introduced into England about the beginning of the seventeenthcentury; but the exact date is uncertain. The earliest trees recorded are twomentioned by Evelyn, 8 which were planted in 1603 by Serjeant Newdigate inHarefield Park in Middlesex. These had attained about 80 feet high in 1679, butfrom inquiries made by the late Dr. Masters, there is no doubt that they have longsince been cut down.Though in its own country the silver fir is a tree of the mountains, yet itattains its greatest perfection in the south and west of England, Scotland, and1 Abstract of Fischer's paper injburn. Roy. Hort. Soc. xxvii. 272 (1902).1 See Kerner, Nat. Hist. Plants, Eng. trans. i. 210, fig. 48 (1898). We have never seen or heard of mistletoe on thesilver fir in this country. 3 gee Mathieu, Flore Foresttire, 529 (1897).4 Staves were found, in 1900, lining the ancient wells in the Roman city of Silchester, Hants; and the wood wasidentified by Marshall Ward with A . pectinata. The casks, from which the staves had been taken, were probably importedfrom the region of the Pyrenees, and had either contained wine or Samian ware. Cf. Clement Reid, in Archaeologia, Ivii.253. 256 (^oi)- 6 Sylva, 106 (1679).Abies 72,7Ireland, under conditions of soil and climate very unlike those of its native forests.Though it will endure the severest winter frosts without injury, yet unless under thecover of other trees, or in very sheltered situations, it is often injured by spring frost,on account of its tendency to grow early. As regards soil it is somewhat critical,for though Boutcher 1 says that he has seen the largest and most flourishing silver firson sour, heavy, obstinate clay, yet I have never myself seen fine trees on any butdeep, moist, sandy soils, or on hillsides where the subsoil was deep and fertile. Healso says it is vain to plant them in hot, dry, rocky situations, and this is my ownexperience on oolite formations, where I have never seen a large or well-developedsilver fir. In the east and midland counties they usually become ragged at the topbefore attaining maturity, and in this country rarely attain a great age withoutsuffering from drought and wind.Though foresters of continental experience recommend this tree for underplanting,on account of its ability to grow under dense shade, yet from an economicalpoint of view it cannot be recommended here; and I do not know of any place inEngland where the financial results of planting the silver fir are, or seem likely tobe, such as would justify growing it on a large scale; partly because of its veryslow growth when young, and partly because its timber is not valued as it is inFrance and Germany. Mr. Crozier's experience 2 is very noteworthy.The silver fir seeds itself very freely in some parts of England, Scotland, andIreland, 3 but the seedlings are so slow in growth and so delicate for the first fewyears, that few survive the risk of frost, rabbits, and smothering. Sir CharlesStrickland tells me that in a wood of silver firs at Boynton, Yorkshire, which weremostly blown down in 1839, he remembers that a few years afterwards the growth ofyoung seedlings was in places so dense that he could hardly force his way throughthem. Some of these self-sown trees are now 6 feet in girth and 60 to 70 feet high,but many are stunted from want of space. Their parents are rough and branchy,dying at the top, and 10 to 12 feet in girth.REMARKABLE <strong>TREES</strong>Though the silver fir will probably be in time surpassed in height and girth bysome of the conifers of the Pacific coast of America, yet at present it has no rival insize among coniferous trees in Great Britain. Perhaps the tallest which I have seenin England is the magnificent tree (Plate 208) which grows in Gates Wood, at thetop of Cowdray Park, Sussex, at an elevation of 500 to 600 feet, and now owing toits being deprived of the shelter of the surrounding trees, likely to be blown down1 Boutcher, A Treatise on Forest Trees, 146 (1775).2 Formerly one of our most reliable trees, but now hopelessly unreliable as a timber crop, owing to its susceptibility toattack by Chermes. Like the larch, our old trees are practically immune to attack, but the difficulty in getting up youngstock experienced throughout the greater part of the country is likely to lead to its extinction altogether as an economicspecies. Has been much recommended by continental trained foresters even of late years for the purpose of underplantingin our Scotch woods, and some of those experiments I saw lately. The result is a hopeless failure in all of them.(J. D. CROZIER.)3 At Auchendrane, near Ayr, according to Mr. J. A. Campbell, there are several acres of self-sown seedlings; and inCounty Wexford I have also seen great numbers.

72,8 The Trees of Great Britain and Irelandby the first severe gale. I measured this tree in 1906 in company with Mr. Roberts,forester to the Earl of Egmont, as carefully as the nature of the ground would allow,and believe it to be still over 130 feet in height; when I first saw it in 1903 it wastaller. It is clear of branches to at least 90 feet and 10 feet 2 inches in girth. Inthe background some spruce which are even taller may be seen in our illustration.I am informed by Mr. F. H. Jervoise, of Herriard Park, Hants, that there wasa silver fir there which probably exceeded this height before its top was broken offabout sixteen years ago. A photograph, taken in 1851, shows the height to havebeen then at least double what it now is, namely 70 feet, and another tree standingnot far off measures approximately 140 feet.In the Shrubbery at Knole Park, Kent, a very large silver fir is now about110 feet high, with a clean bole about 80 feet by 12 feet; but its top is broken off,and it looks as if it might have been much taller.At Longleat there are a great number of very fine silver firs near the Gardens; andalso in the valley at Shearwater, the largest of which I measured in 1903, and foundto be about 130 feet by 16 feet 5 inches in girth. 1 Mr. A. C. Forbes estimated thecontents of this tree at 550 feet, and in the Trans. Eng. Art. Soc. v. 399, givesthe measurements of a group of twenty-seven trees, 120 years old, growing on anarea of ^ of an acre at the same place as follows: Average height, 130 feet;average girth at 5 feet, 9 feet; average contents, 180 cubic feet. Total, 5000 cubicfeet. I doubt whether any similar area of ground in England carries so muchtimber, except, perhaps, a group of chestnut and oak in Lord Clinton's park atBicton. Silver fir requires unusually good soil to attain these dimensions. Plate209 shows a part of this grove which stands at an elevation of about 500 feet ona greensand formation.There is a row of very fine silver firs by the road on Breakneck hill in WindsorPark, one of which I measured as 130 feet by 11 feet, and no doubt many as large,or nearly so, can be found in other parts of the south and west of England; but,as a rule, when the tree attains about 100 to no feet its top ceases to grow andbecomes ragged.Near the great cedar at Stratton Straw less (see Plate 133) there are some tallsilver firs, one of which in 1907 was 131 feet by 9 feet 7 inches; and Mr. Birkbeckinformed me that another, believed to be the tallest tree in Norfolk, and measuring135 feet, had been blown down in 1895 at tne same place.There are some very fine silver firs still standing at Eslington Park, Northumberland, which were planted about 1760, though Mr. Wightman, the gardener, informsme that the largest, which could be seen standing above all the other trees, wasblown down in a gale in December 1894. It measured 122 feet by 21 feet at fivefeet from the ground, and at fifty feet from the ground was still 9 feet ingirth.Almost equal to these are the trees in the Ladieswell Drive, near AlnwickCastle, Northumberland, which I saw in 1907; though not much exceeding 100 feet1 Loudon states that the tallest silver fir known in England in his time was believed to be at Longleat, and measured138 feet high by 17 feet in girth; but this tree cannot now be identified.Abies 729in height, they measure from 14 feet to 16 feet in girth, the largest being estimatedby Mr. A. T. Gillanders, forester to the Duke of Northumberland, to contain about600 cubic feet each.At Rydal Park, Cumberland, Mr. W. F. Rawnsley informs me that a silver firwas felled which contained 420 cubic feet, and doubtless there are others in thenorth-west of England as large. 1In Wales, however, I have seen none remarkable for size, though there aremany places which seem as suitable as those I have mentioned.In Scotland the silver fir attains its maximum of size in the south-west, and ina district where the climate is most unlike that of central Europe; being muchwarmer in winter, cooler in summer, and with a rainfall of 60 to 80 inches and evenmore in exceptional years.On the Duke of Argyll's property at Roseneath are the champion silver firs ofGreat Britain, both as regards age and girth. Strutt figures them in Silva Scotica(plate 6), and states that the largest was then about 90 feet by 17 feet 5 inches.Loudon, twenty years later, gave the height as 124 feet, the age as 138 years, andthe diameter of the trunk as 6 feet; but this height is almost certainly an error, aswhen I visited Roseneath in September 1906, a careful measurement made thelargest about no feet by 22 feet 7 inches, and the other, which stands close by it,105 feet by 22 feet i inch. 2 Plate 210, from a negative for which I have to thankMr. Renwick, is the best I have been able to obtain of these noble trees, whichgrow close to sea-level in deep sandy soil. The Duke of Argyll believes them tohave been planted about 1620 or 1630.Near Inveraray Castle, on the lower slopes of Dun-y-Cuagh, Mr. D. Campbell,the Duke's forester, showed me some splendid silver firs, over 120 feet high and15 feet in girth, and assured me that in his younger days he had helped to measuresome which were much larger; one he believed to have been 24 feet in girth,containing over 800 feet of timber. On the Dalmally road, a little above thestables at Inveraray, are the tallest trees of the species that I have seen in Scotland;one measures 135 feet, or perhaps as much as 140 feet, by 16^ feet; another about135 feet by 14 feet 3 inches; and there may be even taller ones here which I couldnot measure. These splendid trees were, as the Duke of Argyll informs me,probably planted by Duke Archibald in 1750, but their timber is so coarse that itis of little value, and is principally used by Glasgow shipbuilders for keel blocks.Some of the most remarkable silver firs which I have seen in any country areat Ardkinglas, now the property of Sir Andrew Noble, near the head of Loch Fyne.They are described by J. Wilkie, and well illustrated in the Trans. Scot. Arb. Soc.ix. 174, and show a tendency, which I cannot explain, to throw out immensebranches, which, after growing horizontally 10 to 15 feet from the main trunk, turnup and form an erect secondary stem. The largest of these (op. cit. plate 11), according to Wilkie's careful measurement in 1881, was 114 feet high by 18 feet in girth at1 Sir Richard Graham of Netherby Hall, Cumberland, showed me a very remarkable tree in a wood called HogKnowe, which has large spreading branches, 80 paces in circumference, and measures 98 feet by 14^ feet. Mr. Watt ofCarlisle has been good enough to send me a photograph of this tree, taken by his sister." See Card. Chron. xxii. 8, fig. I (1884), and xxvii. 166, fig. 39 (1887), where good illustrations of these trees are given.<strong>IV</strong> D

73 The Trees of Great Britain and Ireland2\ feet. I made it in 1905 about 21 feet at the same height and 14 yards round theroots. Wilkie computed that the main stem contained 557 cubic feet and thebranches 692 cubic feet, including bark, which exceeds the largest tree of thespecies recorded in this country. I certainly have never seen anything surpassingit in bulk, even in the virgin forests of Bosnia, though I have measured a fallensilver fir there which was at least 200 feet high. Another of these trees figured onplate 12 of the same volume, was estimated at 437 feet in the stem, and 449 feetin the ten principal limbs. At the same place is a very fine tree which Mrs. HenryCallender, who showed it to me, called " The Three Sisters," 115 feet high accordingto Wilkie, I made it, twenty-four years later, 120 feet, with a bole only 8 feet long,where it divides into three tall stems nearly equal in height and measuring just abovewhere they separate, 8 feet 4 inches, 8 feet 5^ inches, and 8 feet 7 inches respectively.The Union trees, 1 in the avenue at Auchendrane, Ayrshire, planted in 1707,are six in number, the largest being, in 1902, 97 feet high and 16 feet i inch ingirth. Another tree in the flower garden here, planted at the same time, was 110feet by 16 feet in 1902.In the island of Bute, James Kay describes, in Trans. Scot. Arb. Soc. ix. p. 75,some fine silver firs which grew in a clump north-east of the circle walk in the woodsof Mountstuart, the seat of the Marquess of Bute. They were of immense height(120 feet), and could be seen for miles standing out like an island among this forest ofsylvan beauty. There were nineteen silver firs, five spruce, one Scots pine, and twobirches, all standing on a space of 60 yards square, where they were healthy and notovercrowded. They were very uniform in size, and ran from 10 to 12 feet in girth,ten being straight to the top and nine forked at 30 feet to 60 feet up. 2In other parts of Scotland the silver fir usually attains smaller dimensions, thelargest that I have seen being on the banks of the Tay, near Dunkeld, and atDupplin Castle, where I measured a tree over 100 feet high by 17^ feet in girth.But Mr. W. J. Bean, in Kew Bulletin, 1 906, p. 266, mentions an immense tree,which was blown down on November 17, 1893, near Drummond Castle, when 210years old. The stump of this tree was 6^ feet in diameter, and the cubic contentsare said to have been 1010 cubic feetAt Dawyck, near Peebles, in a cold situation at about 500 feet above the sea,Mr. F. R. S. Balfour showed me some large silver firs which far surpass the larchesgrowing near them, which are believed to have been planted about 1730. Thelargest of the firs is 112 feet by 15^ feet.In most parts of Ireland the silver fir is a thriving tree wherever planted, and seemsto be well suited to the climate. It was probably introduced early in the eighteenthcentury, as, according to Hayes, there were trees 100 feet high and 12 feet in girthin 1794 at Mount Usher, in Co. Wicklow. The largest silver fir in Ireland that weknow of is at Tullymore Park, Co. Down, the seat of the Earl of Roden, growingin a sheltered valley below the house. Col. the Hon. R. Jocelyn, who showed me1 Cf. Renwick, in Trans. Nat. Hist. Soc. Glasgow, vii. 265 (1905).2 Mr. Kay informs me that many of the trees described by him thirty years ago have since been blown down, and I couldnot identify these silver firs when I visited Bute recently.Abiesthis tree in 1908, informed me that it was marked on a plan about 200 years old,and though still vigorous in appearance, it seems to be hollow for some way up. Itmeasures from 115 to 120 feet high, with a girth of 18 feet 10 inches; and at about20 feet from the ground throws out four large branches, which become erect, andform a tree of the candelabra type. (Plate 211.) At Carton, the seat of the Dukeof Leinster, a tree was 16 feet i inch in girth in 1904, but the top had been blownoff by the great gale of 1903. The finest silver firs in Ireland are probably thosegrowing at Woodstock, Co. Kilkenny, where the biggest tree was in 1904 over 120feet high by 15 feet 4 inches in girth. There are also here four trees standing soclose together that they can be encircled by a tape of 30 feet; one of these is 133feet high by 10 feet 10 inches in girth. At Avondale, Co. Wicklow, Mr. A. C.Forbes measured a tree in 1908, 125 feet in height and 15 feet 4 inches in girth.At Tykillen, Co. Wexford, the silver fir grows well and seeds itself freely, but doesnot attain anything like the dimensions above noted. There are fine trees atCastlemartyr, Co. Cork, one of which measures 114 feet by 14 feet 8 inches.TIMBERThough on the Continent the wood of the silver fir is in some districts, andfor purposes where strength combined with lightness is required,1 valued morehighly than that of the spruce or pine, yet in England it is little appreciated,because it seldom comes to market in any quantity, and the trees are rarely cleanenough to make good boards. But I am assured by Dr. Watney that, when slowlyand closely grown, it is distinctly superior in quality to that of the spruce, and that heuses it in preference on his own property for estate building; and Mr. H. E. Asprey,agent to the Earl of Portsmouth at Eggesford, Devonshire, where this tree growsvery well, tells me that he finds the timber quite equal to that of spruce for all estatepurposes. The Marquess of Bath informs me that a lot of 22 trees, averaging140 feet each, were sold privately at 5^d. per foot, and used at Trowbridge formaking tin-plate boxes ; but most of his silver fir timber goes to the Radstock coalpits, where it is used underground.Laslett says 2 that " the pinkish white and scarcely resinous wood works up well,with a bright silky lustre, and is of excellent quality for carpentry and ship-work.It is light and stiff, and like spruce takes glue well. Nevertheless it is as yet farless in request than the latter, though it is employed in the making of paper pulp,as well as for boards, rafters, etc." 8 So little is it known, however, to the Englishtimber merchant that the author of English Timber does not even mention it, and Iam not aware that it is imported to England as an article of commerce.Strasburg turpentine, which was formerly extracted from the resinous glandsfound on its bark and largely used for the preparation of clear varnishes and atone time used as medicine, is now apparently superseded by other resins, though,according to Fluckiger and Hanbury,4 it was still collected to a small extent in theVosges in 1873. (H. J. E.)1 Cf. Mouillefert, Essences Forestieres, 338(1903). 3 Timber and Timber Trees, 343 (1896).3 Christ, Flore de la Suisse, 255 (1907), says that its white wood is delicate and not so much in request as the moreresinous wood of the spruce. 4 Pharmacographia, 6 15 (1879).

732 The Trees of Great Britain and IrelandABIES PINSAPO, SPANISH FIRAlies Pinsapo, Boissier, Biblioth. Univ. Getifrve, xiii. 167 (1838), and Voyage Espagne, ii. 584, tt.167-169 (1845); Masters, Card. Chron. xxiv. 468, f. 99 (1885), xxvi. 8, f. i (1886), and iii.140, f. 22 (1888); Kent, Veitch's Man. Coniferce, 5 34 (1900).Pinus Pinsapo, Antoine, Conif. 6 5, t. 26, f. 2 (1842-1847).Picea Pinsapo, Loudon, Etuycl. Trees, 1 041 (1842).A tree attaining about 100 feet in height and 15 feet in girth. Bark smooth inyoung trees, becoming rugged and fissured on old trunks. Buds ovoid, obtuse at theapex, resinous. Young shoots glabrous, brownish, with slightly raised pulvini.Leaves on lateral branchlets radially arranged, linear, flattened, but thick, rigid,short, £ to f- inch long by about ^ inch wide, gradually narrowing in the upper thirdto the acute apex ; upper surface convex without a median furrow and with eight tofourteen lines of stomata; lower surface with two bands of stomata, each of six orseven lines ; resin-canals usually median. 1 In young plants the leaves are longer andend in sharp cartilaginous points. On cone-bearing branches the leaves are shortand thick, lozenge-shaped in section, with twenty or more lines of stomata on theupper surface, and two bands of stomata of about ten lines each on the lower surface,which has a prominent keeled midrib.Staminate flowers crimson, cylindrical, J inch long, surrounded at the base bytwo series of broadly ovate obtuse scales.Cones sessile or subsessile, brownish when mature, pubescent, cylindrical,tapering to an obtuse apex; 4 to 5 inches long by i^ to if inches in diameter.Scales: lamina three-sided, i inch wide by f inch long, upper margin almost entire,lateral margins nearly straight, laciniate; claw short, obcuneate. Bract minute,situated at the base of the scale, ovate, orbicular or rectangular, denticulate,emarginate with a short mucro. Seed with wing i£ inch long; wing two to threetimes as long as the body of the seed. In cultivated specimens the cones and scalesare usually considerably smaller than in wild trees.Cotyledons z six, convex and stomatiferous on the upper surface, flattish andgreen on the lower surface.HYBRIDSA series of hybrids have been obtained between A . Pinsapo and two otherspecies, A . cephalonica and A . Nordmanniana, of which a full account is given byDr. Masters in his valuable paper on hybrid conifers. 3i. Abies Vilmorini, Masters. 4 This is a tree growing at Verrieres near Paris,which has the following history. In 1867, M. de Vilmorin placed some pollen ofA. cephalonica on the female flowers of a tree of A. Pinsapo. A single fertile seedwas produced, which was sown in the following year; germination ensued and the1 The resin-canals in this species are variable in position. Cf. Guinier and Maire, in Bull. Sec. Bot. France, Iv. 190 (1908).2 Masters, in lift. * Jcurn. Key. Hort. Soc. xxvi. 99 seq. ( 1901). 4 Ibid. 109.Abies 733seedling was planted out in 1868. M. Phillipe L. de Vilmorin 1 states that the treewas in 1905, 50 feet high by 5 feet in girth; and has three main stems, one ofwhich, however, was broken by a storm two years ago. In its habit and foliage itresembles A. Pinsapo more than the other parent. The leaves, however, are longerand less rigid than in A . Pinsapo, and bear stomata only on their lower surface ;moreover their radial arrangement on the branchlets is imperfect. The cones, whichare produced in abundance and contain fertile seeds, resemble those of A . cephalomca,being fusiform in shape ; they have longer bracts than in A . Pinsapo, in some yearsexserted, in other years shorter and concealed between the scales. Seedlings raisedfrom this tree, now four years old, have acuminate sharp leaves like those ofA. cephalonica.2. Abies insignis, Carriere, Rev. Hort. 1 890, p. 230. This hybrid was obtainedin i or 1849 in the nursery of M. Renault at BulgneVille in the Vosges. Abranch of A . Pinsapo was grafted on a stock of the common silver fir (A. pectinata) \and after some years the grafted plant produced cones. Seeds from these weresown ; and of the seedlings raised one-half were like A . Pinsapo, the remainder beingintermediate in character, it was supposed, between A . Pinsapo and A . pectinata ;and the variation was considered to be the result of graft hybridisation. However,at no great distance there was growing a tree of A . Nordmanniana ; and it is moreprobable that the hybrid character of the seedlings was the result of a cross fromA. Pinsapo fertilised by the pollen of A . Nordmanniana. A complete account ofthese seedlings is given by M. Bailly. 23. Abies Nordmanniana sfieciosa, Hort. 2 This hybrid was raised in 1871-1872by M. Croux in his nurseries near Sceaux, the cross being effected by placing pollenfrom A . Pinsapo on female flowers of A . Nordmanniana. A full account of thishybrid is given by M. Bailly. 24. Mosers hybrids. Four different forms, all raised from A. Pinsapo, fertilisedby the pollen of A . Nordmanniana, which were obtained in 1878 by M. Moser atVersailles. Full details are given in Dr. Master's paper, to which we refer ourreaders.DISTRIBUTIONA. Pinsapo has a restricted distribution, being confined to the Serrania deRonda, a name given to the mountainous region around Ronda in the south of Spain.The late Lord Lilford informed Bunbury 3 in 1870 that he had seen it growing onthe Sierra d'Estrella in Portugal ; but we have not been able to confirm thestatement.There are three main forests of this species, none of considerable extent, occurringin localities at considerable distances apart. I visited these forests in December1906, and explain the rare occurrence of the tree as due to the fact, that in the dryclimate of the south of Spain, it can only exist on the northern slopes of mountain> fortus Vilmorinianus, 69, plate xii. (1906). 1902, p. 162, fig. 66.See also Card. Chron. 1 878, p. 438; Rev. Hort. 1889, p. 115, andRev. Hort. 1890, pp. 230, 231. 8 Arboretum Notes, 147 (1889).

734 The Trees of Great Britain and Irelandchains running due east and west; and these are seldom met with. In suchsituations the soil is never exposed to the direct rays of the noonday sun, andpreserves in consequence a great deal of moisture. The tree never grows evenon north-west or north-east slopes, and is strictly limited to aspects looking duenorth.The most important forest is in the Sierra de la Nieve, a few miles to the eastof Ronda. Here the tree extends for several miles in scattered groves on the northslope of the range, growing on dolomitic limestone soil, usually in gullies or underthe shade of the cliffs. It occurs mainly at elevations of 4000 to 5900 feet, thoughit occasionally descends to 3600 feet. In shaded situations and where the soil isdeep, there are dense groves of thriving trees, without any admixture of otherspecies; but at the lower elevations, where there is more sun, the trees are scatteredand mixed with oak and juniper. In exposed situations, at high elevations, the treesare windswept, stunted, and more or less broken. Seedlings are numerous in manyplaces. The largest trees, seen by me, were a group, on the road across themountain from Ronda to Tolox, at a spot called Puerto, de las animas. One ofthese (Plate 212) was 106 feet in height and 13 feet 8 inches in girth; and anotherwith a double stem, not so tall, girthed 16 feet 3 inches. This group is overhung bya precipice, and is at 4700 feet altitude. The stump of a tree, which had been cutdown, showed 240 annual rings and was 32 inches in diameter.The second forest, and by far the most picturesque, lies to the west of Ronda,on the northern slope of the precipitous peak, Cerro S. Cristoval or Sierra delPinar, close to the mediaeval town of Grazalema. The fir grows here on atalus, composed of sharp angular white limestone stones ; and the contrast betweenthe dense mass of green foliage of the tree and the pure white ground from which itsprings, is remarkably beautiful. The stones and pebbles are loosely aggregated ;and beneath the surface they are mixed with a mass of black mould, in which theroots of the tree freely spread. The fir extends along the precipitous side ofthe mountain for about two miles, forming a band of continuous forest, which reachesnearly to the summit of the peak, attaining about 5800 feet altitude, and descendinggenerally to 4000 feet, reaching in one gully to 3600 feet. Seedlings are numerous.There is no undergrowth, except an occasional daphne; but climbers like ivy andclematis are common. None of the trees are so tall as those in the Sierra de laNieve; but many have gigantic short trunks, in one case girthing 25 feet, and areextremely old. In this forest, trees with glaucous foliage, not seen elsewhere, are notat all uncommon.The third wood of A. Pinsapo occurs on the Sierra de Bermeja, which overhangsthe town of Estepona and the Mediterranean coast. This wood, which covers onlya small area, is most accessible from Gaucin, a station on the railway betweenGibraltar and Ronda. Here the soil is disintegrated serpentine rock, and thetree grows on the northern slope, between 4100 and 4900 feet, though stuntedspecimens occur up to 5400 feet. The fir is pure on the precipitous upper partof the mountain ; but lower down is mixed with Pinus Pinaster. The largest tree,which I measured, was 90 feet high by 13 feet 5 inches in girth.Abies 735Isolated groups of a few trees, the remains of former forests, are reported to begrowing on the Sierra de Alcaparain, near Carratraca, north-east of Ronda, and atZahara and Ubrique, not far from Grazalema. Mr. Mosley of Gibraltar, who gaveme valuable help and information, saw A . Pinsapo also growing on the SierraBlanca de Ojen near Marbella.HISTORY AND CULT<strong>IV</strong>ATIONThis species was discovered by Edmond Boissier in 1837. He sent abouthalf-a-dozen seeds to M. de Vilmorin in the same year, and from one of these wasraised the very fine tree, which is now growing at Verrieres 1 near Paris, and whichis certainly the oldest cultivated specimen. This tree was in 1905, 70 feet high by7 feet 3 inches in girth. Abies Pinsapo was introduced into England in 1839 byCaptain Widdrington, 2 who was the first to obtain information about the existenceof a new species of Abies in Spain, though he was anticipated in its discovery byBoissier. (A. H.)In cultivation this has proved to be, all over the southern, midland, and easterncounties, one of the most ornamental of its genus, and is perfectly hardy on drysoils throughout Britain, ripening seed at least as far north as Yorkshire. It is oneof the few silver firs that seems to require lime to bring it to perfection, and thoughit will grow fairly well on sandy soils, it will not thrive without perfect drainage, oron heavy clay. It seems to have a great tendency to divide into several leaders andoften forms a bushy rather than a clean trunk, unless carefully pruned. It is notoften injured by spring frost, and, though not likely to have any economic value, isa tree that should be planted in all pleasure grounds on well-drained soil, andin a sunny situation.The seedlings which I have raised grow at least as fast as those of A . pectinata,and are hardier when young, but require five or six years' nursery cultivation beforethey are fit to plant out.The wood is soft and knotty like that of most of the silver firs when grownsingly in cultivation.REMARKABLE <strong>TREES</strong>Though specimens of this tree of from 50 to 60 feet high are found in manyplaces all over England, we have not measured any which are specially remarkable.The largest recorded at the Conifer Conference in 1891 was a tree reported to be62 feet high by 9 feet in girth, at Pampisford in Cambridgeshire; but thesemeasurements were erroneous, as it now is only 56 feet high by 7 feet 3 inches ingirth. Here there is a remarkable dwarf form 8 of this species, which is only afoot in height, with branches prostrate on the ground for 6 or 7 feet.The largest tree we know of is growing in a sheltered position in moist soil, atCoed Coch, near Abergele in North Wales, the residence of the Hon. Mrs. Brodrick.1 Hortus Vilmorinianus, 69, pi. 7 (1906).a Sketches in Spain, ii. 239.3 This is var. Hammondi, Veitch, Conifers, ed. i. p. 105.