Note: The findings, interpretations, and conclusions expressed in this article are entirely those of the authors. They do not necessarily represent the views of the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development/World Bank and its affiliated organizations, the Executive Directors of the World Bank, or the Governments they represent.

23 December 2022

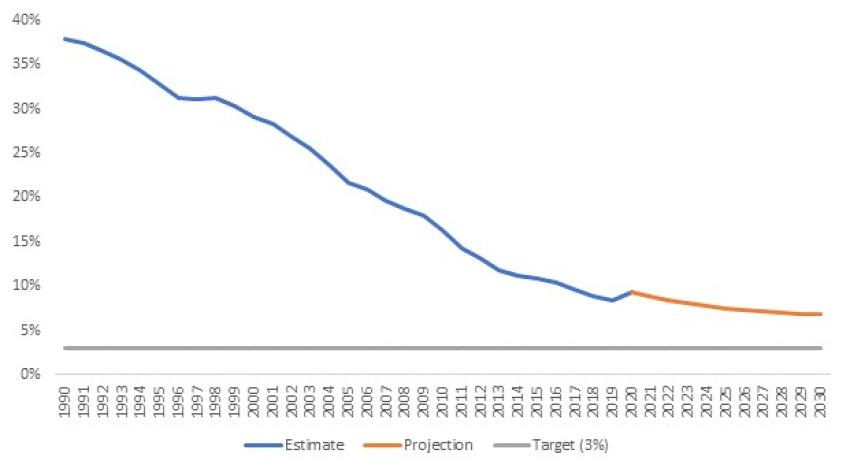

According to the latest Poverty and Shared Prosperity Report (PSPR 2022), published by the World Bank, the global extreme poverty rate declined from 37.8 per cent to 8.4 per cent between 1990 and 2019 (Figure 1). PSPR 2022 included projections showing that the global extreme poverty rate is expected to fall to 6.8 per cent by 2030, which is significantly higher than the World Bank’s target of 3.0 per cent and falls short of Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) target 1.1 of eradicating extreme poverty by 2030. Accelerating the pace of poverty reduction is a complex and difficult task. Instead of comprehensively analyzing the global poverty trend, this article discusses two major challenges to achieving the global targets: (i) the slow pace of poverty reduction in Eastern and Southern Africa and (ii) the lack of frequency and timeliness of poverty data.

Poverty in Eastern and Southern Africa

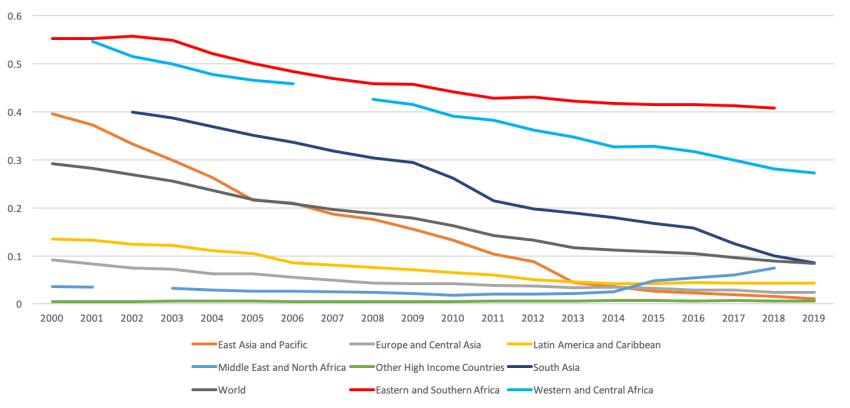

Eastern and Southern Africa is a new sub-group within sub-Saharan Africa that includes 26 countries.1 According to the latest global poverty database, the region had the world’s highest extreme poverty rate—40.8 per cent in 2018 (Figure 2). Moreover, since 2017 it has been the region with the highest number of people living in extreme poverty, surpassing South Asia. As of 2018, almost 40 per cent of the world’s extreme poor, or over 262 million people, live in Eastern and Southern Africa. More importantly, not only is this the region with the highest poverty rate and concentration of the extreme poor, but it’s pace of poverty reduction has also been very slow. The extreme poverty rate in Eastern and Southern Africa has declined by only 0.43 percentage points a year since 2010, less than half the global average of 0.93.

Why has poverty reduction in Eastern and Southern Africa been so slow? There are many possible drivers. First, the population growth rate in the region, at 2.6 per cent in 2019, is more than double the world’s population growth rate of 1.2 per cent. Second, its annualized growth rate of gross domestic product (GDP) per capita between 2010 and 2018 was only 0.1 per cent, while all other regions had an annualized growth rate higher than 0.8 per cent. Third, high inequality is a concern for the region. Five of the world’s ten most unequal countries are in this region, and all but two countries had higher Gini coefficients than the global median.2 Fourth, various shocks, including those related to climate, hit countries in the region more frequently than before. For example, since 2016, Malawi has experienced one drought, two cyclones and the COVID-19 pandemic. In 2022, the Horn of Africa experienced its worst drought in 70 years. The pace of poverty reduction is further exacerbated by surging inflation region-wide. Finally, fragility is an important challenge for this region. It includes multiple fragile States, such as Burundi, Somalia, South Sudan, etc., and refugees from those countries flow into other countries in the region.

Figure 1. Source: World Bank estimates based on Mahler, Yonzan, and Lakner (2022); World Bank, Poverty and Inequality Platform; World Bank, Global Economic Prospects database.

Improving the frequency and timeliness of poverty monitoring

Despite efforts made over the last three decades, the lack of poverty data continues to be a big challenge for global poverty monitoring and identifying policies. Poverty data are available only every seven years on average in low-income countries and fragile States. Such outdated data make it difficult to identify what policies should be implemented to accelerate poverty reduction.

Data collection is not frequent mainly because it is an extremely costly and time-consuming exercise. Fielding a household survey can easily cost millions of dollars, and it often takes two or more years to estimate poverty from the data.

Several new methodologies have been developed and tested to reduce the cost and time required to estimate poverty. The Survey of Well-being via Instant and Frequent Tracking (SWIFT) proposed in The Concept and Empirical Evidence of SWIFT Methodology, published by the World Bank, is one such new methodology. SWIFT uses machine learning and statistical techniques to dramatically reduce the cost of and time for poverty estimation, so that even low-income countries and fragile States can monitor poverty and inequality annually or quarterly. The application of SWIFT for global poverty monitoring is still limited but increasing as the reliability and usability of SWIFT improve. For example, SWIFT was used to break a nearly ten-year drought of poverty data in the Democratic Republic of Congo and estimate the incidence of poverty during the currency crisis in Zimbabwe in 2019.

Figure 2. Source: Authors’ calculations based on the Poverty and Inequality Platform.

Beyond SWIFT, there are many efforts to increase the frequency and quality of poverty data. For example, innovations in data collection techniques, like Computer Assisted Personal Interviews (CAPI), reduce the cost and time of traditional household survey data collection. Also, the World Bank has been increasing the grant and credit for statistical capacity-building in low-income countries and fragile States. Both innovations and increased funding are critical to improving the reliability of global poverty monitoring and identifying policy interventions and assistance to accelerate poverty reduction.

Notes

1 The Eastern and Southern Africa region includes Angola, Burundi, Botswana, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Comoros, Eritrea, Ethiopia, Kenya, Lesotho, Madagascar, Mozambique, Mauritius, Malawi, Namibia, Rwanda, the Sudan, Somalia South Africa, South Sudan, Sao Tome and Principe, Eswatini, Seychelles, Tanzania, Uganda, Zambia, and Zimbabwe.

2 Household survey data from the World Bank’s Poverty and Inequality Platform global database as of October 2022.

The UN Chronicle is not an official record. It is privileged to host senior United Nations officials as well as distinguished contributors from outside the United Nations system whose views are not necessarily those of the United Nations. Similarly, the boundaries and names shown, and the designations used, in maps or articles do not necessarily imply endorsement or acceptance by the United Nations.