Work And Process

The Shadow Of The World James Welling's Cameraless And Abstract Photography

The Shadow Puppeteer

Spring 2008 Noam M. ElcottThe Shadow Of The World James Welling's Cameraless And Abstract Photography NOAM M. ELCOTT Spring 2008

THE SHADOW OF THE WORLD JAMES WELLING'S CAMERALESS AND ABSTRACT PHOTOGRAPHY

WORK AND PROCESS

NOAM M. ELCOTT

The Shadow Puppeteer

Before his aluminum-foil landscapes and the wreckage of drapes and phyllo dough, before his Polaroids and eerie Los Angeles architectures, before James Welling even acquired his first view camera, he staged a series of cameraless photographs, or photograms, of hands.

Hands—the most readily available subject in the darkroom—are a classic motif of cameraless photography (just as photocopied hands are a standard product of office mischief). Photograms are the direct traces of objects on a photosensitive surface, made without optics and without lenses. Man Ray made hand photograms, as did László Moholy-Nagy (an important influence on Welling). Early X-ray images of hands helped popularize the invisible ray. Few photography students today fail to leave behind at least one cameraless handprint.

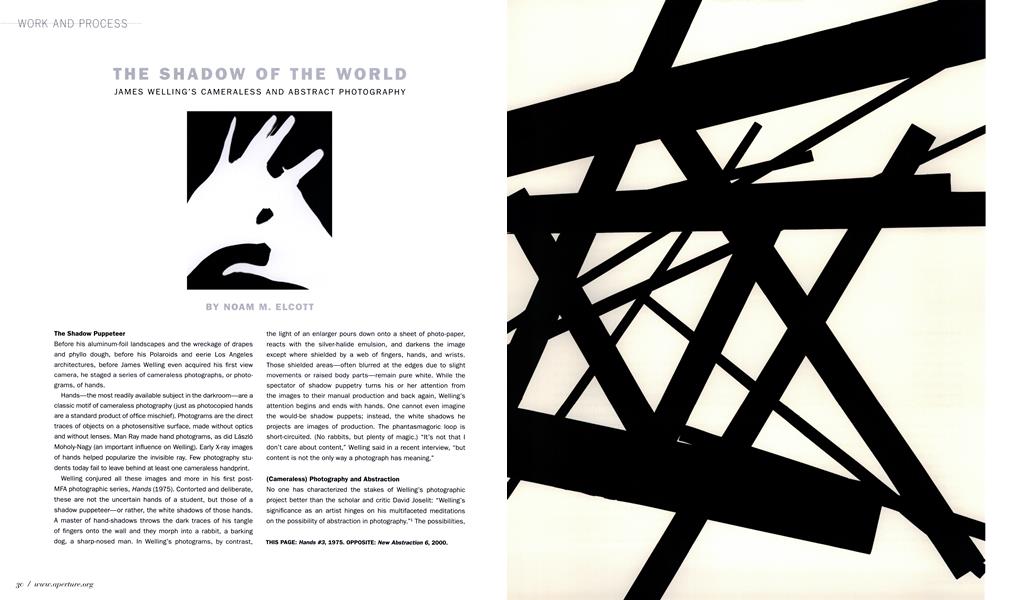

Welling conjured all these images and more in his first postMFA photographic series, Hands(1975). Contorted and deliberate, these are not the uncertain hands of a student, but those of a shadow puppeteer—or rather, the white shadows of those hands. A master of hand-shadows throws the dark traces of his tangle of fingers onto the wall and they morph into a rabbit, a barking dog, a sharp-nosed man. In Welling’s photograms, by contrast,

the light of an enlarger pours down onto a sheet of photo-paper, reacts with the silver-halide emulsion, and darkens the image except where shielded by a web of fingers, hands, and wrists. Those shielded areas—often blurred at the edges due to slight movements or raised body parts—remain pure white. While the spectator of shadow puppetry turns his or her attention from the images to their manual production and back again, Welling’s attention begins and ends with hands. One cannot even imagine the would-be shadow puppets; instead, the white shadows he projects are images of production. The phantasmagoric loop is short-circuited. (No rabbits, but plenty of magic.) “It’s not that I don’t care about content,” Welling said in a recent interview, “but content is not the only way a photograph has meaning.”

(Cameraless) Photography and Abstraction

No one has characterized the stakes of Welling’s photographic project better than the scholar and critic David Joselit: “Welling’s significance as an artist hinges on his multifaceted meditations on the possibility of abstraction in photography.”1 The possibilities, it turns out, are endless and endlessly varied. Abstraction is not a monolith, but a starting point. Is there an organic connection between abstraction and photograms? It is certainly not a man datory one: Welling's I-lands project is not abstract, and neither is his more recent photogram series of plumbago blossoms, Flowers (2004-06). To draw a link between abstraction and photograms is not to reduce the categories to their essentials, but to remove them from their boxes. This is a central insight Welling gained when he embarked in 1998 on two projects: one representational, New Landscapes, and the other abstract, New Abstractions. In a 2004 interview, Welling spoke of the unex pected overlaps he discovered between the two modes:

With the New Landscapes I began showing the black border of the negative as part of the image, something I'd never done before. I began to realize that the edge of the negative represents the shadow of the camera, the opaqueness of matter. It casts a shadow on the negative, so it's a photogram as well. With the New Abstrac tions I was working with photograms, and the black shapes in those pictures were directly related to the black edge of the negative in the New Landscapes. Since 1998 I've become sensitized to the idea of the photogram as a shadow of the world coexisting with the optical image made by the camera lens.

An early name for photography ("writing of light") was sciagraphy ("writing of shad ows"). The cameraless darkness in Welling's New Abstractions and New Landscapes is at once the "shadow of the world" and the shadow of the camera. As the artist increasingly turns to photo grams, these divisions-like those separating the puppeteer's shadows and hands-dissolve.

In the history of photography (as in Welling's career), photograms have been deployed to a variety of ends during widely disparate phases of photographic abstraction: from nineteenthcentury science and the occult to the interwar avant-garde and popular photography, modernist formalism, postmodernist his toricism, right up to the all-encompassing digital present. In his invocation of these incongruous elements, Welling is able to construct a history of photographic abstraction from a range of cameraless photography practices. Indeed, he has characterized his own postmodernist project as "something like redoing mod ernism, but with a sense of history."

Nature Prints and Spectrographs

Flowers and other botanical specimens are an urmotif of cam eraless photography. As early as 1843, Anna Atkins, for example, composed cobalt-blue cameraless cyanotypes of British algae. In the nineteenth century, botanical photograms were a subset of so-called nature drawings,2 a category that included etchings, engravings, "nature prints" (created by pressing a given objecta leaf, a shell-onto a prepared plate that is then used as a printing surface), and "natural illustrations" (made by inserting real specimens into the pages of a book). Natural illustrations and photograms offer a similar sense of immediacy, and both lack the chromatic range of etching and engraving. Examples of natural illustrations can be seen in Welling's work Diary of Elizabeth and James Dixon (1840-41)/Connecticut Landscapes, which he photographed over a ten-year period beginning in 1977. Here, the inserted flowers and ferns-which leave impressions on the opposing pagesprovide a connection between two com ponents of the artist's project: diary and landscape.

Welling's now extensive series of flower photograms both alludes to and departs from the long tradition of cameraless botani cal prints. For the first iteration of Flowers (2004), he took plumbago blossoms from his yard, arranged them in the darkroom on pieces of 8-by-b-inch black-and-white film, and made exposures of them with an enlarger. In the negative silhouette that ensued, brightness is modulated not by the color of the blossoms but by the opacity of the leaves and their proximity to the film. Welling then shone colored light through the black-and-white negatives to create a series of positive photograms in each of Newton's seven primary colors: red, orange, yellow, green, blue, indigo, and violet. In the newest Flowers works, Welling introduces a spectrum of colors into each image. Photography, according to Flowers, is as intimate as a curled petal and as abstract as a wavelength.

With the late nineteenth-century discovery of X-rays and sponta neous radiation, photograms were used as a means to transcribe particle-wave emissions. In physicist Henri Becquerel's landmark 1896 illustration of "spontaneous radiation," the white shadow of a metal Maltese Cross may be the most recognizable content, but the true subject of this photogram is the abstract (but utterly real) phenomenon of radioactivity. (Similarly, Welling's plumbago blossoms serve as a stunning vehicle with which to capture and represent his actual subject: light phenomena.)

Beaumont Newhall, a formalist at heart, had an understanding of this disjointed relation between the photogram process and subject, writing in a 1948 discussion of the work of Moholy-Nagy: “The photogram maker’s problem has nothing to do with interpreting the world, but rather with the formation of abstractions. Objects are chosen for their light-modulating characteristic: their reality and significance disappear.”3

Welling’s principle achievement in the Flowers series lies, first, in a dual rejection: of a science that is concerned solely with the signified, and of a formalist practice that is anchored only in the signifier. Further, he has succeeded in synthesizing two historically opposed photogram traditions: nature prints, with their direct material traces, and spectrographs, the direct traces of immaterial radiation. In Welling’s work, flowers dissolve into spectral apparitions and light is given tangible shape in such a way that material and immaterial realities fuse. While Moholy-Nagy considered flower photograms to be “primitive,” he held up abstract color photograms as the pinnacle of the medium. But not a single image in Welling’s Flowers series is abstract in Moholy-Nagy’s modernist sense; instead, each invokes 150 years of nature prints and a century of spectrographs. Flowers relinquishes every lens but that of history; ultimately, it is from these nineteenthcentury sparks that the images emerge so beautifully, so unapproachably, in the present.

"Between abstract geometrical tracery and the echo of objects"

In a 1929 survey of New Vision photography, German photographer and critic Franz Roh declaimed that the photogram “hovers excitingly between abstract geometrical tracery and the echo of objects.”4 Few works attain this “ghostly" (Roh uses the term geistert) balance better than Welling’s Tile Photographs (1985), in which plastic tiles were placed on a light box and photographed from overhead. Although not technically cameraless, these works are something of an inverted photogram: the light source and the photosensitive surface have exchanged places, and the lens of the enlarger has been replaced by the lens of the camera. The result is nearly indistinguishable from a positive print of a cameraless photograph—a coincidence Welling pursued just over a decade later with his New Abstractions series. Here he began with 8-by-10 photograms of strips of heavy Bristol board paper, producing flat, white bands on a dark ground. He then scanned these photograms digitally and made high-contrast negatives. The final gelatin-silver prints were produced from these negatives, and so enclose a second level of geometric abstraction. It is the translation of nearly perfect tonal gradations into the rigid geometry of pixels; the pixels are visible in the final print and mirrored macroscopically in the binary white-black visible forms.

Today, nearly ten years further along, Welling has begun to explore in more depth the middle phase of this process—

digitization. The images in his Quadrilaterals series (2007) are the first computer-generated images Welling has exhibited. In these works, he introduces fine gradations of grays that upset the whiteblack balance and imply cast shadows rather than flat silhouettes of abstract forms. Nevertheless, the division between figure and ground is precarious and threatens to collapse. If Welling’s photograms are at once shadows of the world and shadows of the camera, these instances of digital chiaroscuro are neither. They are ghostly shadows without referents, geometrical echoes whose tracery is neither abstract nor representational but lies somewhere in between.

Welling has in fact remarked: “In my abstract photographs there’s virtually no figure. They’re all ground.” ITAS (2001), from his Dégradés series begun in 1991, is a unique chromogenic photogram produced in the darkroom through direct exposure to light under variable color filtration. The bands and planes of color assert the reality of the photo-surface and at the same time provide a third dimension of pure opticality and light. They are reminiscent of small works by Mark Rothko—that is, the height of modernist abstraction. But Welling’s title hints at another allegiance: dégradé is the term used by studio photographers to describe the gradated sheets of color used as backdrops in commercial photography. One is reminded of the infamous Cecil Beaton photo-spreads in Vogue of March 1951, in which gowned models posed before Jackson Pollock’s Autumn Rhythm (1950) and other paintings. Here, modernist artwork and photo-backdrop were presented as one and the same. The uncomfortable union forged in Beaton’s fashion shoot is distilled intricately in Welling’s Dégradés series: neither fashion nor Abstract Expressionism makes an explicit appearance but their ghosts haunt every image. This is modernist abstraction, but with a sense of history: the nightmare of a photobackdrop and the unfulfilled aesthetic promise of pure form.

Screens

Moholy-Nagy once judged photograms to be “the most successful recording thus far of light striking a projection screen—in this case, the sensitive layer of the photographic paper.”5 Current screen technology—from handheld devices to flat-panel displays in and outside the home—relates less to projection than to tiny cells of electrically charged plasma and excited phosphors (to cite but one variant). What is more, “screen savers”—among the most widely disseminated forms of abstraction—were introduced precisely to prevent the photogrammatic phenomenon singled out by Moholy-Nagy nearly eighty years earlier: a permanent record of light striking a screen. Ours is a society of transmission, not of traces. Photograms appear to have little purchase on the visual interface of our digitized culture.

Yet it is in his recent Screens series (2004-05) that Welling stages his most extensive intervention into contemporary imaging. As in earlier projects, the series consists of abstract images that contain a torrent of associations. The dimensions of 5 (2005) mimic widescreen aspect ratio, and the abstract modulations suggest a screen saver burned into the surface of a plasma television. The faint grid intimates not only halftone printing (in which a screen is used to convert an analogue photograph into a field of dots), but also a low-resolution digital image viewed on a highdefinition apparatus. These associations are not wrong—just as Welling’s 1981 picture The Waterfall conjures the entity named in its title even as it literally depicts drapes and phyllo dough. But unlike The Waterfall, these associations hint at rather than hide the image’s constituent components and mode of production.

Welling employed a C-print negative, now the reigning process for large-format photographers, especially when coupled with Lambda or other digital-exposure techniques. He did not expose it digitally, however, but rather constructed a makeshift contraption of crumpledup window screens through which he projected the colored light of a Durst horizontal-projection mural-enlarger directly onto the negative. Rather than exploit the camera lens as a window onto the world, Welling executed a cameraless photograph of window screens.

With his Screens series, Welling augments the optical images made by the lens not with the shadow of the world or the shadow of the camera, but with the “shadow of the screen,” literal and metaphoric. Throughout his career, he has used abstraction and cameraless photography to affirm the texture of discourse, the opacity of matter, the reality of mediation, and the vicissitudes of light—in sum, the specifics of the photographic medium, its properties, and its histories. In Screens, Welling has embarked on a series whose lodestar may be modernist light projections and avant-garde photograms, but whose immediate position is this “postphotographic” age where medium-specificity yields to digital animations on electronic screens. Rather than pit modernist photography against digital technologies, Welling has tried to operate in that gap between the two. His Screens mark a momentary fissure in the digital and artistic landscape of today. ©

1 David Joselit, “Surface Histories,” Art in America (May 2001): 141.

2 See Carol Armstrong, “Cameraless: From Natural Illustrations and Nature Prints to Manual and Photogenic Drawings and Other Botanographs,” in Ocean Flowers, ed. Armstrong and Catherine de Zegher (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2004).

3 Beaumont Newhall, “Review of Moholy’s Achievement” (1948), in Moholy-Nagy, ed. Richard Kostelanetz (New York: Praeger, 1970), p. 71.

4 Franz Roh, “Mechanismus und Ausdruck/Mechanism and Expression," in foto-auge, ed. Roh and Jan Tschichold (Stuttgart: Akademischer Verlag Dr. Fritz Wedekind, 1929).

5 Laszlo Moholy-Nagy, The New Vision (1929/1938) (Mineóla, N.Y.: Dover, 2005), p. 85.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Dialogue

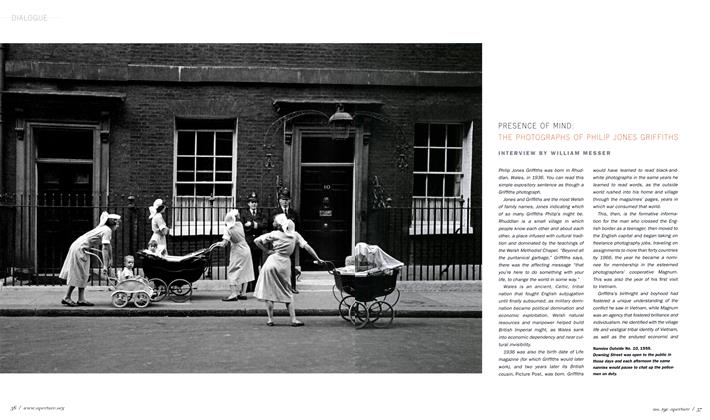

DialoguePresence Of Mind: The Photographs Of Philip Jones Griffiths

Spring 2008 By William Messer -

Under The Influence

Under The InfluenceIn A Lonely Place

Spring 2008 By Gregory Crewdson -

Essay

EssayFrom Ecstasy To Agony: The Fashion Shoot In Cinema

Spring 2008 By David Campany -

Before The Lens

Before The LensJh Engström: Looking For Presence

Spring 2008 By Martin Jaeggi -

Portfolio

PortfolioColour Before Color

Spring 2008 By Martin Parr -

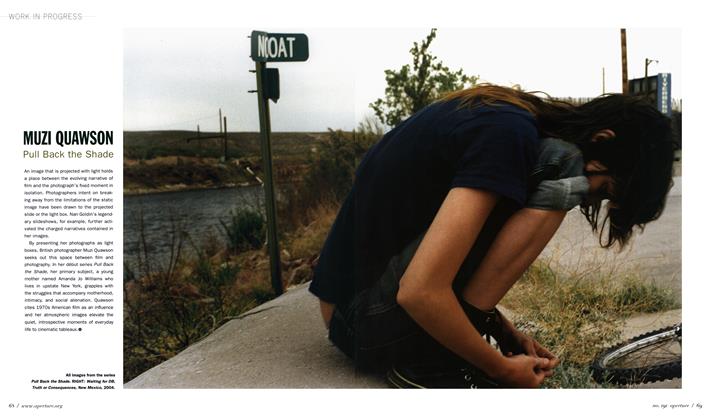

Work In Progress

Work In ProgressMuzi Quawson Pull Back The Shade

Spring 2008

Subscribers can unlock every article Aperture has ever published Subscribe Now

Work And Process

-

Work And Process

Work And ProcessJane Hammond's Recombinant Dna

Summer 2008 By Amei Wallach -

Work And Process

Work And ProcessThe Unblinking Judy Linn

Summer 2012 By Francine Prose -

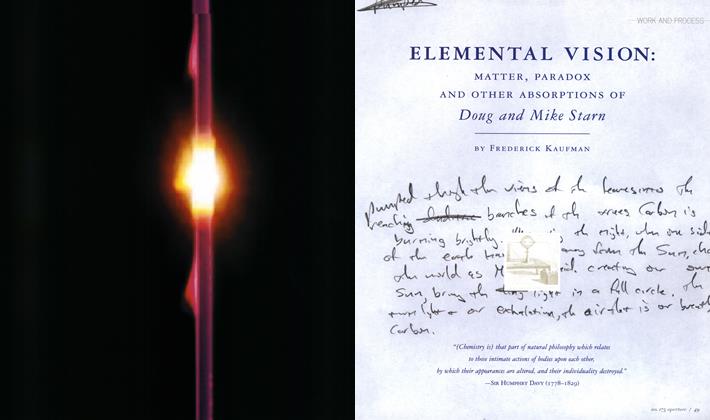

Work And Process

Work And ProcessElemental Vision: Matter, Paradox And Other Absorptions Of Doug And Mike Starn

Summer 2004 By Frederick Kaufman -

Work And Process

Work And ProcessSongs Left Out Of Nan Goldin's Ballad Of Sexual Dependency

Winter 2009 By Greil Marcus -

Work And Process

Work And ProcessHiroshi Sugimoto: Enigmatic Objects

Spring 2005 By John Yau -

Work And Process

Work And ProcessChuck Close Daguerreotypes

Summer 2000 By Lyle Rexer