LISE SARFATI SHE

PHOTOGRAPHER'S PROJECT

SANDRA S. PHILLIPS

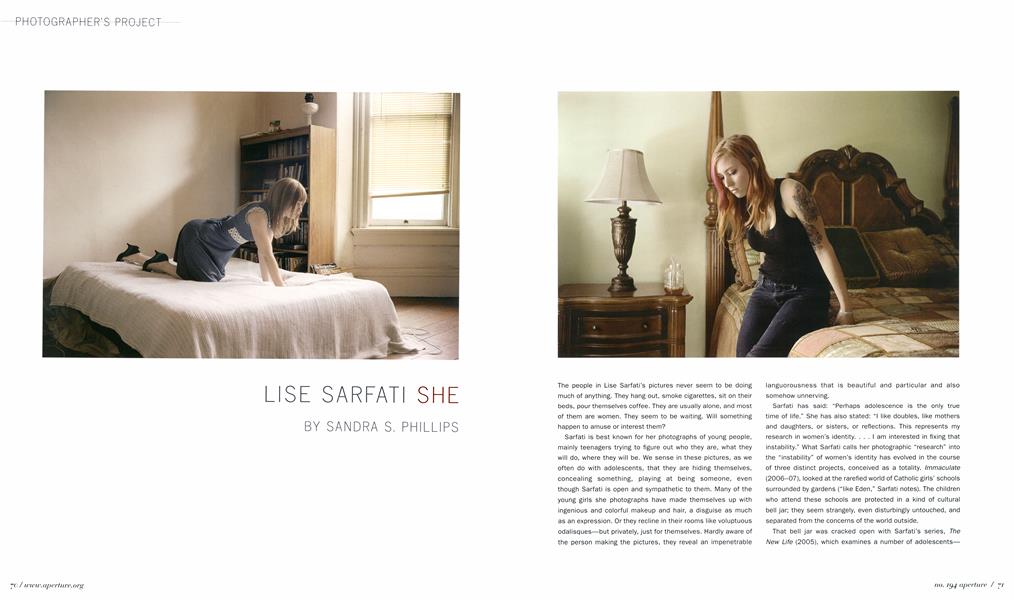

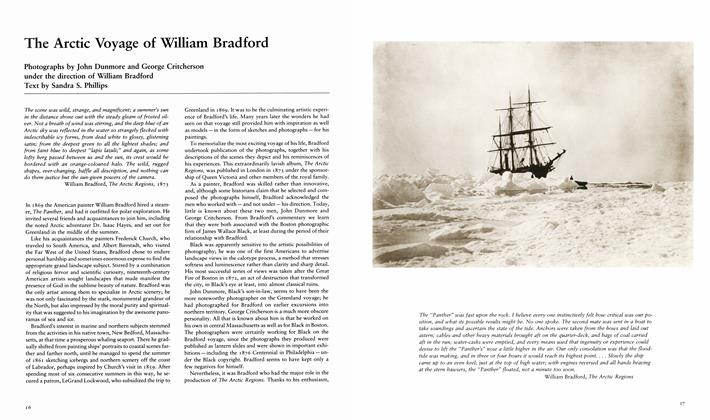

The people in Lise Sarfati's pictures never seem to be doing much of anything. They hang out, smoke cigarettes, sit on their beds, pour themselves coffee. They are usually alone, and most of them are women. They seem to be waiting. Will something happen to amuse or interest them?

Sarfati is best known for her photographs of young people, mainly teenagers trying to figure out who they are, what they will do, where they will be. We sense in these pictures, as we often do with adolescents, that they are hiding themselves, concealing something, playing at being someone, even though Sarfati is open and sympathetic to them. Many of the young girls she photographs have made themselves up with ingenious and colorful makeup and hair, a disguise as much as an expression. Or they recline in their rooms like voluptuous odalisques—but privately, just for themselves. Hardly aware of the person making the pictures, they reveal an impenetrable languorousness that is beautiful and particular and also somehow unnerving.

Sarfati has said: “Perhaps adolescence is the only true time of life.” She has also stated: “I like doubles, like mothers and daughters, or sisters, or reflections. This represents my research in women’s identity. ... I am interested in fixing that instability.” What Sarfati calls her photographic “research” into the “instability” of women’s identity has evolved in the course of three distinct projects, conceived as a totality. Immaculate (2006-07), looked at the rarefied world of Catholic girls’ schools surrounded by gardens (“like Eden,” Sarfati notes). The children who attend these schools are protected in a kind of cultural bell jar; they seem strangely, even disturbingly untouched, and separated from the concerns of the world outside.

That bell jar was cracked open with Sarfati’s series, The New Life (2005), which examines a number of adolescents— both boys and girls—living in towns and cities across the United States. Among the subjects in this series are two sisters, Sloane and Sasha, who, when Sarfati first met them in 2003, were coping with a radical geographical, cultural, and psychological transition. They had recently moved to Oakland, California, from Phoenix, where they had lived with their grandparents in a large, conventional suburban home near their father, attending a rather proper school that required uniforms. Sarfati photographed the sisters’ reinvented, unconventional lives with their mother in an Oakland loft.

What is perhaps most astonishing about the pictures of Sasha and Sloane in The New Life is that the girls are hardly recognizable as the same people, though according to Sarfati the photographs of them were nearly all taken on the same day. The most memorable picture—one of Sarfati’s most recognized—is the portrait of Sloane in a long orange wig, wearing a brilliant red dress and enormous sunglasses, glancing downward. In another picture, again in the funky Oakland loft, she is blond and smokes a cigarette, looking at the photographer bemusedly, inquisitively.

Sarfati’s current project, She, in a sense doubles the stakes of her investigation into familial pairings: it revisits the two sisters, now a few years older, alongside their mother, Christine, and her sister, Gina. Sloane and Sasha no longer live with their mother; now each girl shares an apartment with other roommates in Oakland. Gina too lives in Oakland, while Christine lives in Los Angeles, pursuing a singing career.

Sarfati is careful to point out that though her two last series share two subjects, they are different projects. Here, no one is photographed with anyone else; everyone is seen alone, in her own space. Sarfati is interested in the implied drama enacted here between the two younger women and two older women. The mood of these pictures, in less expert or sensitive hands, might recall the emotional level of a soap opera—one has the sense that the issues are ongoing, as they are on TV dramas. Though there are anxieties and real competitiveness manifested in the way they all dress and comport themselves, we also sense an emotional cohesion among these four women. They look as though they belong to the same tribe, will stick together, are conscious of one another, worry about one another.

As difficult as it is to tell who is who in the earlier pictures, it is perhaps even harder now. Not only do the two younger girls look different in almost every picture, the older women have slender, angular bodies, like the girls’. Christine, their dark-haired mother, can hardly be distinguished from her sister, Gina, who is naturally blond but wears a black wig. Christine has the same inward gaze and the same outward sense of costume her daughters have. The mother and the aunt have tattoos on their shoulders. Christine puts on a bridal dress for the camera, a costume she keeps even though she was never married in it. Like her children, the mother is shown in intense thought, caught up in her own imagination; we see her hesitating on the stairs between the house and the street, as though trying to remember something she has forgotten.

Sarfati photographed Sloane sitting in a San Francisco home, holding up a toddler’s one-piece wrap, examining it as though she is trying to find something in it. Sloane is at her first job, as a babysitter, and as she folds the clothes, seated on the floor with the light coming in from the window behind her, she seems older in her new blond hair than the self-conscious-looking young woman in red hair standing just inside a room in Oakland. Sarfati notes that Sloane’s sister, Sasha, has a tattoo that reads “Mother” on her shoulder. So while it may seem that roles are malleable, that self-invention is not only possible but liberating, Sarfati finds the essential and perceptible links that weave these women together.

In her attention to dress and posture, Sarfati presents personality as a protean entity, as though you can change your mood, and who you think you are, with the same ease as you change your clothes. But there is also a kind of impenetrable core that resists change, and this torsion is what Sarfati finds especially telling. The girls can have pink hair or blond hair or dark hair—have they forgotten what color their hair really is? Sloane can look like Alice closing the door to her Wonderland room in her high-waisted blue dress, or have the sophistication and sexual tension of an older woman when she crawls over a bed in high heels or lounges on another bed, throwing her newly blond hair over so it glances the polished floor below.

Perhaps it is not surprising that none of these women live in any of the spaces where they are photographed; none of these rooms is an actual home—instead, they are substitutes for what home represents. Sarfati is discreet: she is a friendly observer, not an imposing one. Not much is asked; not much is told. What she finds so expressive is the powerful psychological resonance of her subjects—so real and palpable it is almost like having another person in the room.

Sarfati is interested in the lives of people who live not in the biggest cities, but in smaller, less heroic ones, where life is slower. She finds it easier to get to know people in such places: they tend to be more open, more inviting, and she says she discovers a kind of parallel between her subjects and the places where they live, particularly in these relatively quiet places. Pictures in The New Life were made in Austin, Portland, New Orleans, and elsewhere. Sarfati is attracted to the appearance of “normalcy.” She observes that these places are unlike France, for instance, where architecture can dominate the people who live and work in grand spaces.

Sarfati grew up in Nice, on the Italian border, where summer tourists visit the beaches on the Mediterranean Sea. She lived for ten years in Russia, where she says she learned “the feeling of being nowhere in an undetermined territory.” She prefers the United States now, she says, because of its “immensity. . . . Space is a condition to realize ourselves.” Since 2003 she has spent more than half of her time here.

Sarfati observes: “I am interested in marginality, in immaturity, in naïveté, in illusion, in fictions, in transitions, in the fact that at a certain moment in life there is no limit. I would like my photography to pose a question rather than make a precise statement.” One cannot look at her pictures without thinking that Sarfati, like many Europeans, has been touched by an existentialist acquaintance with dread, loneliness, and other modern anxieties of the postwar period. When she was young she was part of a group that followed Guy Debord’s Situationist ideas; she was interested in those who wrote about the immaturity of the culture, and who resisted the conventionality and authoritarianism of the prewar past: the Polish novelist Witold Gombrowicz, the German dramatist Frank Wedekind, the French poet Gérard de Nerval. Probably most important to her, however, was the writing of Julia Kristeva, the feminist, structuralist theorist who, as a psychoanalyst, is interested in developmental psychology, especially the ties between mothers and their daughters. Kristeva’s 1989 book Black Sun is a meditation on depression and melancholia shared between mothers and daughters: she writes of this relationship both theoretically and poetically, referring to the 1853 Nerval poem “El Desdichado” (especially the phrase “le soleil noir de la Mélancolie”: “The Black Sun of Melancholia”).

Sarfati says: “I am not interested in psychology but I am interested in psychoanalysis.” She is responsive to tensions, to the situation itself—but it would be wrong to say that she is a romantic, or that she is interested in storytelling. She has found the people she photographs because they are compelling to her; she finds out about their lives later. “I am not interested in biographical details even if they could be informative,” she says. “Indeed, they are not central to my approach. When I started working with [these women], I was not aware of their family story and their relationships.”

Here in the United States we consider physical appearance to be mutable. Our popular culture is largely directed toward adolescents and at the same time is based on an ideal of perpetual adolescence: its tastes, its look. (How many aging rock stars do we need to see who persist in not growing up—who look and act like teenagers?) We also have come to believe—if you follow television or the Web—that much of what we want or miss in our lives can be satisfied by buying things, and for women, by buying things to adorn ourselves, to change or “enhance” our appearance. On the other hand, we seem not too interested in inquiry, or in poetry (although we are anxious about religion on some essential level). Sarfati’s pictures, respectful and noninvasive, of these women and what they invisibly share are an imaginative meditation not only on who they are, but also on who we are—beyond what we look like and what we wear—what we bring to life and what we might expect of it.©

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Portfolio

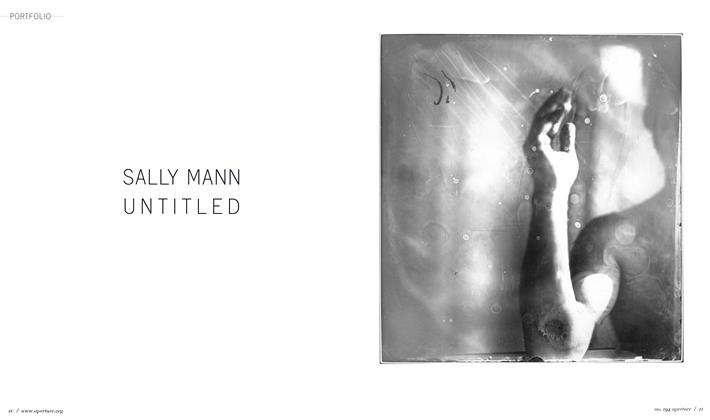

PortfolioSally Mann Untitled

Spring 2009 -

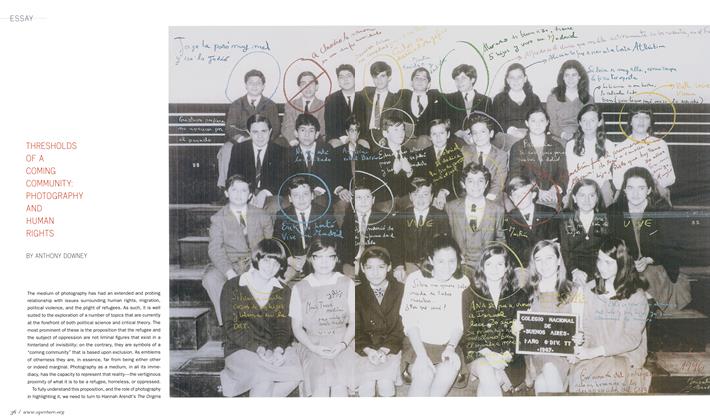

Essay

EssayThresholds Of A Coming Community: Photography And Human Rights

Spring 2009 By Anthony Downey -

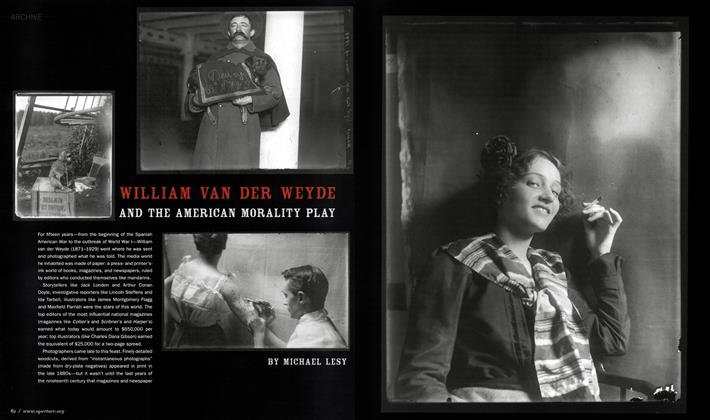

Archive

ArchiveWilliam Van Der Weyde And The American Morality Play

Spring 2009 By Michael Lesy -

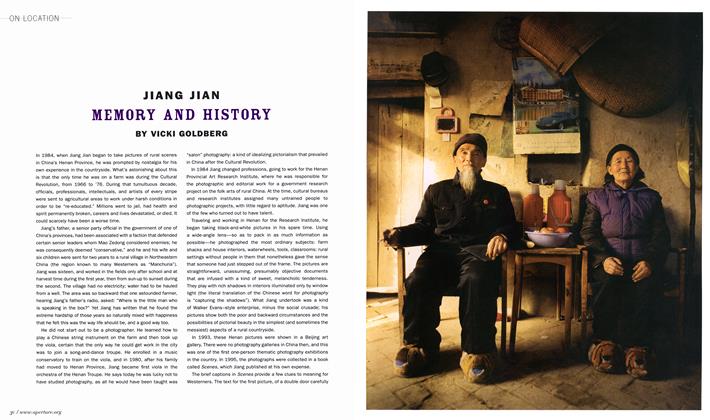

On Location

On LocationJiang Jian Memory And History

Spring 2009 By Vicki Goldberg -

Mixing The Media

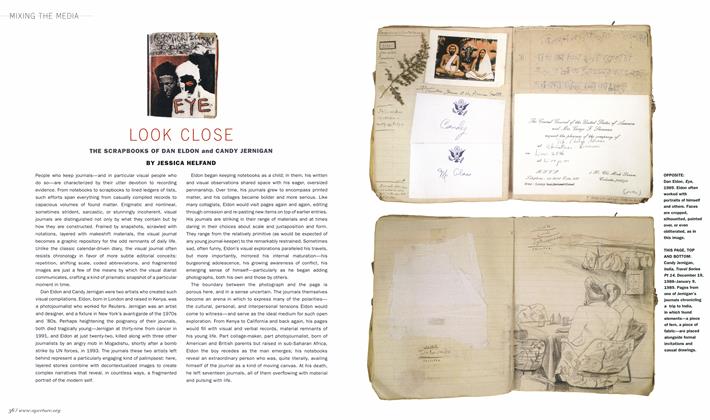

Mixing The MediaLook Close The Scrapbooks Of Dan Eldon And Candy Jernigan

Spring 2009 By Jessica Helfand -

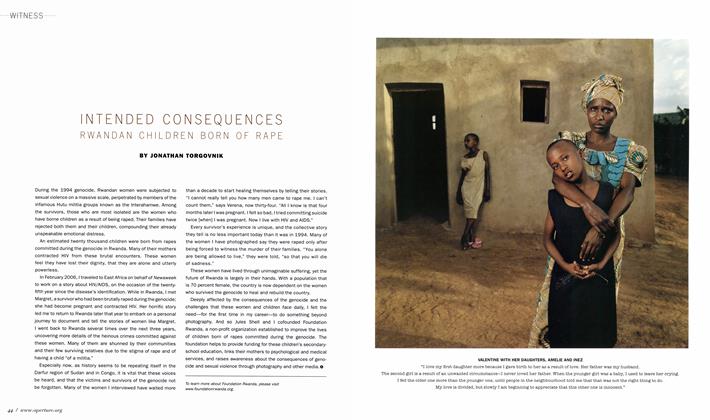

Witness

WitnessIntended Consequences Rwandan Children Born Of Rape

Spring 2009 By Jonathan Torgovnik

Subscribers can unlock every article Aperture has ever published Subscribe Now

Sandra S. Phillips

Photographer's Project

-

Photographer's Project

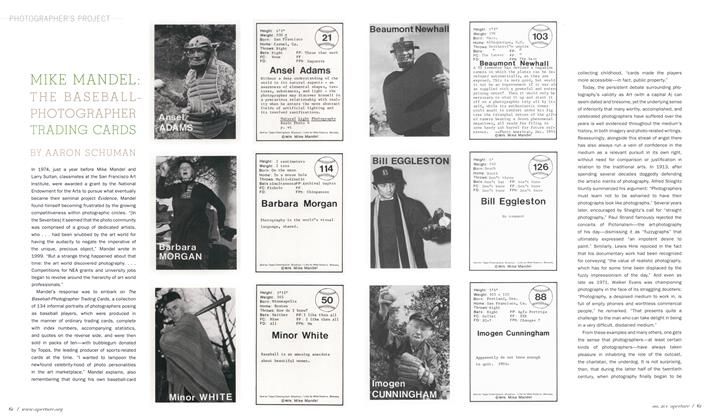

Photographer's ProjectMike Mandel: The Baseball-Photographer Trading Cards

Fall 2010 By Aaron Schuman -

Photographer's Project

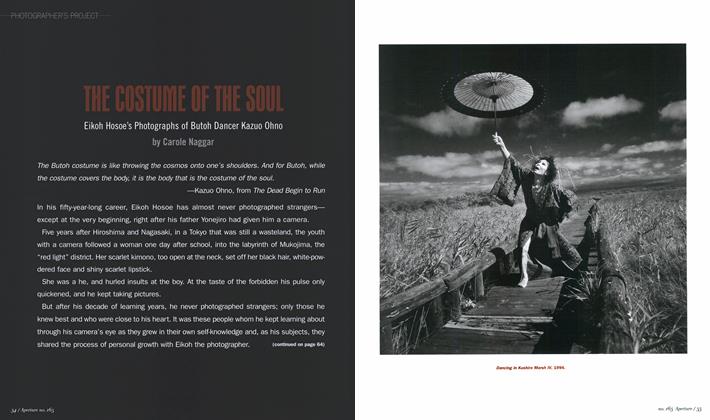

Photographer's ProjectThe Costume Of The Soul

Winter 2001 By Carole Naggar -

Photographer's Project

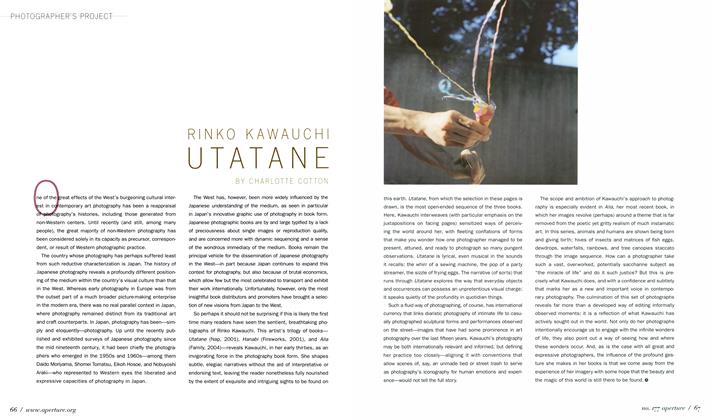

Photographer's ProjectRinko Kawauchi Utatane

Winter 2004 By Charlotte Cotton -

Photographer's Project

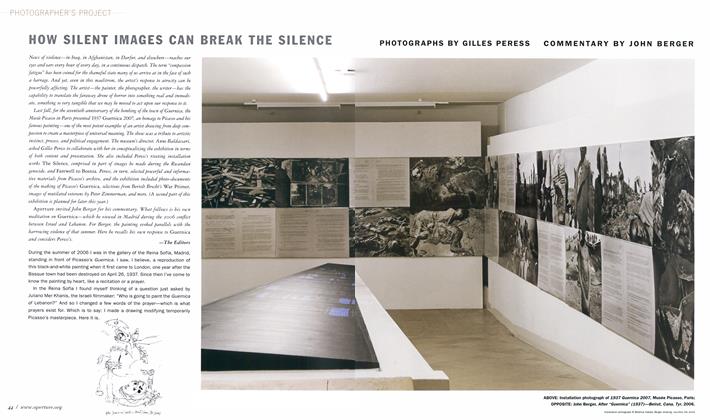

Photographer's ProjectHow Silent Images Can Break The Silence

Summer 2008 By John Berger -

Photographer's Project

Photographer's ProjectVenice 1943

Summer 2011 By Paolo Ventura -

Photographer's Project

Photographer's ProjectLavina

Spring 2011 By The Editors