ArtSeen

Ugo Rondinone: nuns + monks

On View

Gladstone GalleryApril 30 – June 18, 2021

New York

This is a theatrical piece in three scenes. The main attraction of Ugo Rondinone’s current show at Gladstone are the “actors”: three large-scale, brightly polychromed bronze sculptures. But the stage itself, the environment these figures occupy, provides a great deal of context beyond the enigmatic titles that identify Rondinone’s actors as nuns and monks. The pace of the exhibition is carefully choreographed as a series of revelations that begins the moment one enters the gallery’s front door.

Rondinone has modified Gladstone’s space, a fact that is evident on entering the main gallery, where the walls are covered in a mottled gray plaster. But the artist’s presence is also felt before we reach this space, as he has added a grand gate to its entrance that suggests the blunt neoclassicism of 1930s Italian fascist architecture. The gate is clean and geometric, but it also recalls a much more archaic aesthetic of power—the gargantuan architecture of Persepolis or Tiryns comes to mind as well. Through the gate looms the first of Rondinone’s new works, blue red nun (2021), which completely fills the doorway and blocks the view into the chamber. If we accept a slower pace of perception and don’t charge right in, we experience the doorway but have no real sense of what comes next. There is an intimacy to our encounter with this giant being or object, which stands in for the classic trope of the gatekeeper. Perhaps this monolithic form will ask us a riddle or set of questions: a Python-esque “what is your favorite color?” would be fitting.

The three sculptures within the chamber are all roughly twice the height of the viewer, and the chamber’s dimensions are large enough to encompass the sculptures so that their scale seems human and we feel tiny. The forms have an intuitive figural quality in the way that human eyes for millennia have detected sleeping giants in the landscape, while their designation as nuns and monks provides an intimidating socio-religious subtext. orange yellow nun, black green monk, and blue red nun (all 2021) evoke flinty rough-hewn rock forms like the earliest human tools, Oldowan bashers, axe heads, and scrapers. Like these tools, it isn’t always that easy to tell if Rondinone’s sculptures have been formed by human hands, or just naturally accumulated a series of chips and breaks, but the smaller forms placed on top tells us that their figural arrangement is certainly intentional.

As a non-Catholic New Yorker, my opinion of monks and nuns centers on benevolent types inhabiting the Cloisters and various PBS docudramas, but my mother’s accounts of her childhood and a particularly dreaded “Sister Mary” gave me a momentary glimpse into the world of trauma and horror that can be inflicted by these characters. So in effect, once we are past the first gatekeeper, we find ourselves in a gray room crowded with yet more of these larger-than-life, threatening gatekeepers. Rondinone’s aim—with his bright primary colors and matte surfaces as luscious as buttercream icing—may be to make his characters radiant and divine, but to me they also come off as bullies all the same.

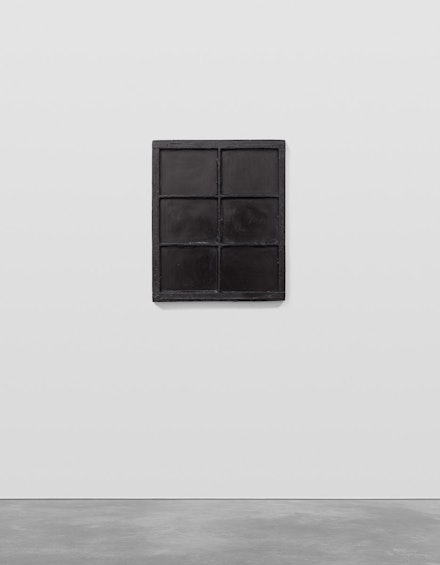

The third act of Rondinone’s rhapsodic drama centers on the last work that one becomes aware of in the exhibition: two men by the sea 1817 (2021). This is part of a series of works in which Rondinone applies the titles of well-known and canonical artworks to the forms of derelict window frames, cast in various metals. In this case he uses bronze and the title of one of Caspar David Friedrich’s bleak landscapes. In nuns + monks the position of this window is particularly reminiscent of fellow tortured Catholic Robert Gober’s placement of windows in room-sized installations—for Gober these are stand-ins for confessional windows, or perhaps an inaccessible means of escape. While Rondinone’s three oversize figures seem to be guarding the black portal, they are not actively preventing the viewer from approaching and examining it. But one is always aware of their presence. The six-pane window is cast from an object which itself is an accumulation of DIY fix-ups. The wooden edging around the glass was long ago replaced by filler, and one can almost hear the whole construction creak as the window is opened or closed. There is a bit of reflection in the cast of the glass, implying a sort of imaginary illuminated depth to the object.

Is there a moral to Rondinone’s play? Gazing into the blackened bronze window pane reminded me of the end of one of my favorite childhood novels, Taran Wanderer by Lloyd Alexander (1967), in which the youthful hero navigates all sorts of hardships in search of a mirror which will reveal his destiny. At the end he finds himself in a dark cave gazing at his reflection in a puddle. It’s a classic device—“you always knew what was there to begin with”—familiar from The Wizard of Oz and countless other fables and myths. As Rondinone shows us in his own version, the set-up matters more than the ending.