ArtSeen

Michaël Borremans: The Acrobat

On View

David ZwirnerApril 28 – June 4, 2022

New York

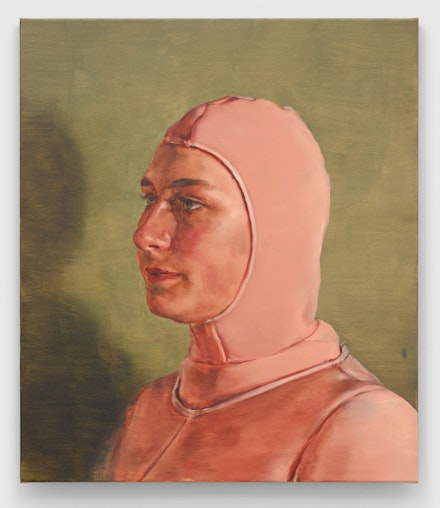

In this series of eight portraits and seven enigmatic landscapes on wood and paper, Michaël Borremans plays with the nature of types, both as a subject and process in painting. Borremans has the advantage of being a respected figurative oil painter who is simultaneously a contemporary artist: he has the entire history of figurative art at his disposal. In this cycle of portraits, the artist dialogues with, appropriates, and lampoons everyone from Bellini to Manet to Jenny Saville. The subjects of Borreman’s portraits are fresh-faced young people, some with face-paint, but most are simply gazing outwards without much emotion. They are in costume, but these costumes do not seem to actually indicate what the subject is engaged in. The Acrobat (2021), The Pilot, (2021), The Apprentice (2022), The Racer (2022), and The Witch (2022) seem to be presented to us more so as philosophical premises, as in “imagine that this person is a(n) ________:” what does that mean?” The paintings get right to the heart of why artists make portraits: are they capturing an emotion or creating an historical document? Are we supposed to glean something factual from the details or merely empathize with a specific person at a brief moment in their lives, now past?

In The Acrobat, the sitter is emotionally neutral, painted in 3/4 pose. It is only the single luminous light source, casting a shadow on the wall by the figure, that lends a morose air to the picture—but this is clearly a detail—gloominess—that Borremans would like us to question in terms of his subject. Just because a person is sitting near a candle doesn’t necessarily mean they’re melancholy. With many of these images, the background is sketched in a watery oil skein—the brushstrokes notable against the much more thickly laid down paint of the figure. In The Double (2022), the subject glistens in the light, conveying a more frenetic lively energy, again a sensation almost completely attributable to the palette and the paint placement rather than the subject. The background is more distinct and we get the sense that she is sitting in front of numerous canvasses—again the fiction of the costume and title is betrayed by the revelation that this is all just an invention of the artist. Borreman’s rides this theme as far as it can go in a sense—painting two canvasses The Cutter (2022) and The Racer (2022) that feature the same mustachioed wide-browed man in ochre face-paint. Literally face-painting on a painted-face: does make-up make the character?

Further to this level of emotional doubt—not simply manipulation—is a literal discussion of the nature of types. Here Borreman’s has dipped into the Impressionist tradition, creating several small paintings on wood (at least one panel comes from the side of a wooden wine box, but the reference to Seurat’s cigar boxes is clear) and paper. The images are also similarly Impressionistic and Post-Impressionistic in subject—pastoral vignettes seemingly sited in parks or forests, with groups of well-dressed people looking at a large, mysterious glass case that seems to contain a selection of individuals. This mysterious monument/display appears without explanation, sometimes freestanding at ground-level, such as With Animals (2021) or sunken below-grade, like Maya Lin’s Vietnam War Memorial (1982), as in the series of paintings Five Writers (Design for a Sculpture) [2021]. We are asked to inhabit the roles of the visitors to this strange display, and to wonder what it means to look at a writer, and by extrapolation, a painter, or perhaps even ourselves.

The most gripping work in the show is The Witch (2021) a portrait of a teenage boy in a gray and brown sweater with a white line between the two blocks of color. His face is again almost emotionless, but he holds up his hand, of which we see four fingers extended, straight and tense. This gesture is enough to inject an almost explosive indication of a narrative. The Witch can be contrasted to The Pilot, (2021) in which the same sitter sits in a bizarre puffy, satiny get-up, with a domed balaclava headpiece. Both of these figures are creatures of Borreman’s studio—same sitter, same general expression, but modulation of costume and similar lighting, and the addition of a simple hand gesture has a completely transformative effect. Through this series of distinct, but arbitrary details the artist is questioning our ability to trust what we see, and where that knowledge comes from—is it the painter, the subject, the light, and/or the long list of assumptions with which we entered the gallery?