ArtSeen

Dario Escobar: Encrypted Messages

On View

Almine RechEncrypted Messages

March 9–April 22, 2023

New York

In Dario Escobar’s latest exhibition, the artist has put aside the soccer balls and skateboards to tackle new encrypted messages found in reclaimed metal signs taken from the Latin American countryside. Escobar is known for his extended reflections on what it means to be an artist from Guatemala. By repurposing popular and commercial objects, he gives us an opportunity to rethink Guatemalan history and culture in a global context.

On a series of road trips through Guatemala and Southern Mexico, Escobar found a peculiar amount of old metal signs on the side of the road, many of which were riddled with bullet holes. With no one around to explain what happened, the meaning of these signs was profoundly enigmatic. Perhaps they were used for target practice, or maybe were remnants of a gunfight. For Escobar, “they represented things [he] did not understand.”

Inspired by these found objects and their inherent violence, Escobar saw in them a direct relationship to the political brutality that has plagued Guatemala for decades. Wanting to repurpose these pieces yet maintain their history, the artist added gold foil onto the perforated surface of the signs. The use of gold foil is a nod to Baroque techniques of the Guatemalan past, where historically Guatemalans would transform commodity objects imported from China, and those would end up in the country’s urban markets.

In works such as Mensajes cifrados N°25 (2022), Escobar has manipulated these once-discarded signs in countless ways, transforming them into artifacts emblazoned with gold. Mensajes cifrados N°25 takes two old Pepsi signs and stacks them one above the other—the bottom of which is placed upside-down. The two signs are connected by continuous stripes of gold foil, creating a color-blocked, abstract artwork that layers one history on top of another.

Comparing these works to the incredible architecture of Antigua, similarities are obvious. The architectural style of colonial Antigua reflects the gold leaf on Mensajes cifrados N°31 (2022), reflecting the golden-yellow Baroque buildings. In Antigua, the buildings all have extravagant white trim, cupolas galore, decorative stucco carvings, and Solomonic columns. Most interestingly, the traditional Baroque style of architecture in Antigua was tailored to the weather. Because of the position of the tectonic plates and exaggerated volcanic and earthquake activity in the area, Guatemalans constructed their buildings as single-story, with thick walls and low bell towers. Just as the Guatemalans adapted their architecture to fit their surroundings, Escobar reappropriates the metal signs to reinforce their Guatemalan heritage. In Mensajes cifrados N°31, Escobar layers four irregularly shaped signs on top of one another, and they are placed perpendicularly on the wall. Though the signs are different shapes and sizes, they all line up with the placement of gold leaf. The bullet holes are just like the cupolas in Antiguan Baroque architecture, like a constellation of small halos of light.

These works are inherently Guatemalan, but they are also reminiscent of Western art history in their use of repurposing discarded materials to highlight questions surrounding commerce, capitalism, politics, and culture. Just like Duchamp and the Dadaists working with collage, or the Junk Art movement of the 1950s, the works on view take objects and regenerate them into new compelling artforms.

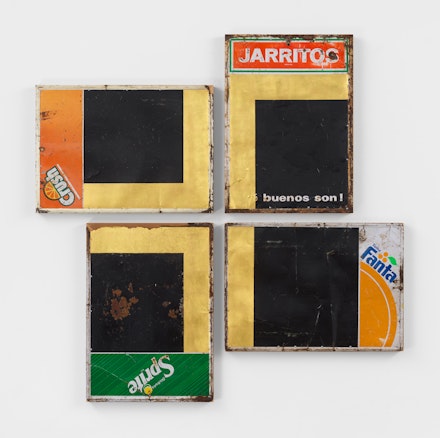

Take the work Mensajes cifrados N°30 (2022), where Escobar has placed four metal soft drink advertisements—Jarritos, Crush, Sprite, and Fanta—into an irregular square formation. Each piece of rusted metal has a black square imbued within a larger yellow rectangle. Is this a reference to Malevich’s revolutionary Black Square? It would make sense, as Escobar and Malevich have much in common. The Black Square was created in an effort to completely abandon depicting reality, instead inventing a new world of shapes and forms. When Malevich created the Black Square, the world was in chaos: the social revolution in Russia was brewing, the first World War was taking place, and the Bolshevik uprising and October Revolution were about to begin. The turbulent political and social upheavals in Guatemala recall much of that tragic history.

Another nod to Malevich is found on the adjoining wall, where Escobar has placed a large metal bottle cap sculpture very high on the wall. When Malevich exhibited his Black Square, he too placed it high on the wall. This was a sacred spot for the Russian Orthodox, and it was the typical place for the icon of a saint to hold in a traditional Russian home. It is of special and spiritual significance, and maybe this holds true for Escobar, as a beacon of hope for the future of his country and its art.