EUGÈNE ATGET MUTE WITNESS

ARCHIVE

GEOFF DYER

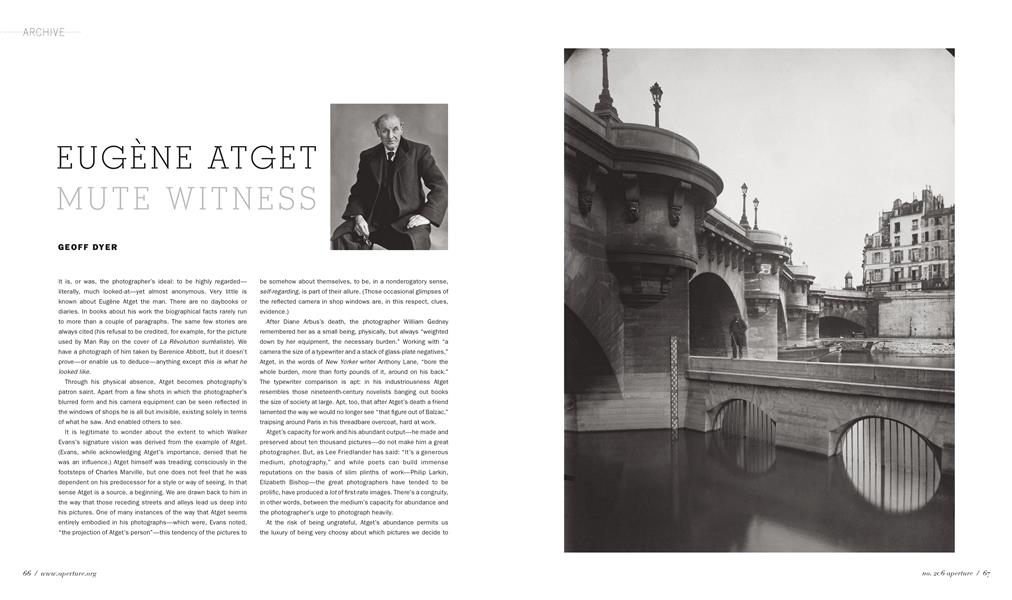

It is, or was, the photographer's ideal: to be highly regarded— literally, much looked-at—yet almost anonymous. Very little is known about Eugène Atget the man. There are no daybooks or diaries. In books about his work the biographical facts rarely run to more than a couple of paragraphs. The same few stories are always cited (his refusal to be credited, for example, for the picture used by Man Ray on the cover of La Révolution surréaliste). We have a photograph of him taken by Berenice Abbott, but it doesn’t prove—or enable us to deduce—anything except this is what he looked like.

Through his physical absence, Atget becomes photography’s patron saint. Apart from a few shots in which the photographer’s blurred form and his camera equipment can be seen reflected in the windows of shops he is all but invisible, existing solely in terms of what he saw. And enabled others to see.

It is legitimate to wonder about the extent to which Walker Evans’s signature vision was derived from the example of Atget. (Evans, while acknowledging Atget’s importance, denied that he was an influence.) Atget himself was treading consciously in the footsteps of Charles Marville, but one does not feel that he was dependent on his predecessor for a style or way of seeing. In that sense Atget is a source, a beginning. We are drawn back to him in the way that those receding streets and alleys lead us deep into his pictures. One of many instances of the way that Atget seems entirely embodied in his photographs—which were, Evans noted, “the projection of Atget’s person”—this tendency of the pictures to be somehow about themselves, to be, in a nonderogatory sense, self-regarding, is part of their allure. (Those occasional glimpses of the reflected camera in shop windows are, in this respect, clues, evidence.)

After Diane Arbus’s death, the photographer William Gedney remembered her as a small being, physically, but always “weighted down by her equipment, the necessary burden.” Working with “a camera the size of a typewriter and a stack of glass-plate negatives,” Atget, in the words of New Yorker writer Anthony Lane, “bore the whole burden, more than forty pounds of it, around on his back.” The typewriter comparison is apt: in his industriousness Atget resembles those nineteenth-century novelists banging out books the size of society at large. Apt, too, that after Atget’s death a friend lamented the way we would no longer see “that figure out of Balzac,” traipsing around Paris in his threadbare overcoat, hard at work.

Atget’s capacity for work and his abundant output—he made and preserved about ten thousand pictures—do not make him a great photographer. But, as Lee Friedlander has said: “It’s a generous medium, photography,” and while poets can build immense reputations on the basis of slim plinths of work—Philip Larkin, Elizabeth Bishop—the great photographers have tended to be prolific, have produced a lot of first-rate images. There’s a congruity, in other words, between the medium’s capacity for abundance and the photographer’s urge to photograph heavily.

At the risk of being ungrateful, Atget’s abundance permits us the luxury of being very choosy about which pictures we decide to concentrate on. We can discard all manner of images and still be left with a surfeit. I don’t mind reading about nineteenth-century interiors in Balzac, Flaubert, or Dickens but, even when photographed by Atget, I can hardly bear to look at them. They’re too oppressive, heavy with furnishing and knickknacks, burdened with Victorianness. (British hegemony was such that even a Republic like France enjoyed its own Gallic version of the Victorian era.) Joseph Brodsky was right: “There’s no life without furniture,” but the accoutrements from that era sometimes seem more deathlike than life-giving. One look at these interiors of Atget’s and you feel claustrophobic, suffocated. This, of course, is a tribute to the pictures’ quality, to the way they are stuffed, like cushions, with what they depict.

Ditto the clothes. Terrible to live—and die—in those rooms, and awful to have to wear those clothes that look and feel like interior decoration with arms and legs attached, or, if you prefer, like a form of exterior decoration designed with the body in mind. Jackets and coats look like they weigh about the same as a sideboard, a sideboard you can clamber into and walk around in.

There are not many people in Atget’s pictures—John Szarkowski estimates that “not two in one hundred of his pictures include people as significant players, and few of this two percent can be thought of as portraits”—and I rarely find myself dwelling on the photographs that feature people prominently. If the scale of Atget’s project is reminiscent of Balzac’s then his is a comédie humaine largely devoid of humans. It seems appropriate: the photographer who is identified by his absence producing pictures in which people are everywhere suggested by their absence. Or in which they are mere spectators, onlookers sharing our curiosity—“Where’d everybody go?”—playing their part in the pictures’ interrogative mode. Walter Benjamin famously wrote that Atget photographed Paris as if it were the scene of a crime; the nature of that crime is unclear but there are, occasionally, a few witnesses whose testimonies may or may not stand up to cross-examination.

So, my personal edit of the Atget archive would include no interiors, no furniture, and, for the most part, few or no people. Obviously, there’s no reason why anyone should give a damn about my whims and preferences—unless they coincide with or are in some kind of alignment with (are even, conceivably, formed by) the essential gravitational pull of the pictures themselves. I like the outdoor photographs of empty streets and deserted parks—and these are the pictures in which Atget’s Atgetness is most clearly manifest.

The long exposure times used by Marville for his photographs of Paris drastically emptied the streets of moving things and people. Pedestrians passing slowly survived as smeared vestiges of themselves: blurred, incorporeal, insubstantial, ghostly. Soon after the invention of photography, in his 1845 Suspiria de Profundis—and directly after mentioning the daguerreotype— Thomas De Quincey wrote of being “haunted" by “ghostly beings moving amongst us.” Working with faster exposure times, Atget did most of his photographing between March and October, often early in the morning, soon after the sun was up, when there were fewer people around. Even so, in some pictures there is the blurred residue of someone walking quickly past, as if it were still occasionally possible to catch traces of these ghostly beings on film. Hence Colin Westerbeck’s conclusion in Bystander, his 2001 history of street photography, that “Old Paris was for Atget a necropolis, a city from the past inhabited by ghosts.” For Benjamin this emptiness was Atget’s defining quality: “The city in these pictures looks cleared out, like a lodging that has not yet found a new tenant.” Note that, while Westerbeck is reminded of the people who are no longer there, Benjamin’s image puts us in mind of people who are not yet there (which in turn raises the possibility that those crimes are yet to be committed). Both share the idea of the pictures being inhabited by people who are not there, by fugitive witnesses and the photographer’s invisibly suggested representatives.

The corollary of the relative lack of foot traffic is that the streets and buildings—the things that are there—are granted a permanence that is palpable, utterly intransigent. Atget’s walls are impregnable. Closed doors look like they can withstand the siege of centuries; open ones look like they will never shut. A mixed blessing, this: bread, in Atget’s pictures, never looks fresh—but it looks like it will never go stale either.

Something similar can be said of Atget’s photographs themselves. We tend to forget that for part of Atget’s long career he was photographing at the same time as pioneering modernists such as Edward Weston and Paul Strand. So, strictly speaking, it was slightly misleading of me to talk about nineteenth century novelists and Victorian interiors—some of Atget’s best work was made after the publication of Eliot’s Waste Land and Joyce’s Ulysses, and well after Picasso painted Les Demoiselles d’Avignon and the coming of Futurism—but the pictures urge us and themselves back in time. Partly this is because the Paris photographed by Atget is old and predates these cultural milestones. (To make the same point the opposite way: would Atget’s pictures have predated themselves in this way if he had photographed new—rather than old—Paris?) Partly it is because his work lacks the conspicuously experimental, manifesto-fueled strategies that underwrote the modernist project—though this, conversely, is what gives much of his best work its quality of floating free of a specific period.

It is no accident that this discussion has drifted in the direction it has. Something about Atget’s pictures encourages one always to reflect on time and the permanent evidence of its passing. Anthony Lane found himself succumbing to precisely this temporal hypnosis. “You are left with the extraordinary sensation that perspective is a matter not only of space but of time: in front of your eyes it is high noon, but day seems to be breaking at the end of every street.” If the spatial and the temporal can stand for each other in this way then those characteristic elements of the Atget pictures mentioned earlier—streets or alleys winding their way into the depths of the picture—effectively reach back not only into the distance but into the past. (This may well be something that Evans derived from Atget: using the receding vista as a way of penetrating back through “a stack of decades.”)

In Benjamin’s observation about Atget’s street scenes resembling a lodging waiting for its future tenants, we notice that time, in certain of Atget’s pictures, stretches in both directions— and, in spatial terms, well beyond the city of Paris. Consider the pictures he made of buildings and neighborhoods in the process of being torn down. A good number of those demolitions were done in 1913-14, just prior to the outbreak of World War I. A later picture (1924-25), of chairs outside a café, is perhaps suggestive of the men who did not come back from the front, but these photographs of half-demolished buildings also look forward to the general condition of many cities in Europe—especially Germany— in the aftermath of World War II. Roland Barthes said photographs were prophecies in reverse—but they can be straightforward prophecies, too.

This matter of time prompts us to go back to the photographs again, to further refine our search and edit, to ask in which pictures this abiding interest in time, its passing and persistence, is most deeply imprinted. Which pictures—which subjects—tell us most about time?

There are two subject areas, I think. First, pictures involving water, the Seine, most obviously, where the river flows past or interacts either with man-made structures—bridges, buildings—or with the slower cyclical changes of the seasons as registered by trees. The key picture in this regard is of the man standing by the Pont Neuf (1902-3), next to a marker measuring the height of the river so that it becomes a record or gauge. If time is a river then this picture serves a kind of chronometer—a watch!—and calendar. (Barthes barely gives Atget the time of day in Camera Lucida; recalling that there are moments when he himself “detest[s] photography,” Barthes asks: “What have I to do with Atget’s old tree trunks?”—which is passing strange, given his delighted realization that cameras were originally “clocks for seeing.”)

Lakes do not flow. Timeless and unchanging, they reflect the way that things change around them. To that extent they’re like the still center of the clock face. There’s a feeling, in Atget’s pictures of lakes and pools in Sceaux, Versailles, and Saint-Cloud, of deep, non-human time—against which the bustle of peopled time pits itself in vain.

It is in photographs of statuary, however, that time imprints itself and Atget’s genius reveals itself most lucidly. Marguerite Yourcenar, reflecting on the composition of her 1951 novel Mémoires d’Hadrian (Memoirs of Hadrian), remarks on “the motionless survival of statues,” which are “still living in a past time, a time that has died.” She has in mind specifically the head of Antinous Mondragone, which has been removed from its original setting and time (second century C.E.), and placed in a museum—effectively, a mausoleum. The statues photographed by Atget may be rooted in a past time but, because they remain at large in the world, that time lives on in them. They age, as we do—but far more slowly. It is said that in the Falkland Islands the fluctuating climate is such that one can experience four seasons in one day. That’s pretty much what a year feels like from a statue’s point of view anywhere in the world. And the years, inevitably, take their toll. Of certain statues in Florence, Mary McCarthy wrote: “Battered by the weather, they have taken on some of the primordial character of the elements they endured.” In the case of the Paris statues photographed by Atget, that sentence needs to be recast in the present continuous: they still endure.

Atget is the godfather of the purely documentary style, the man who established what, for Szarkowski, was “photography’s central sense of purpose and aesthetic: the precise and lucid description of significant fact.” That is the magic of photography—the magic that enables Atget, in these pictures, to make statues sentient: to depict them from their own point of view, as if gazing into a mirror—mute witnesses to their own captivity.

I think it was Henri Cartier-Bresson who said that by moving the camera a couple of feet or by a few degrees the world in a picture could be comprehensively reconfigured. Unable to move their eyeballs even a fraction, statues are permitted no such freedom. With no conception of space, they exist solely in relation to time. Their consciousness is entirely and narrowly of time. Allowed into the slot of their consciousness, we retain a sense of the fleeting human time of the people who sit or pass nearby—even if they are nowhere to be seen.

Inevitably, there are a few photographs in which we see both statues and water, pictures in which we get both a multiplied idea of time and the sense that the image is self-conscious or, in the best possible way, full of itself. Lakes are miniphotographs, brimful of the scenes that surround and frame them. (They might even be considered reservoirs of the optical unconscious, revealed—according to Benjamin—by the invention of photography.) Sometimes the exposure times flatten out the wind-rippled surface of the water and cause reflections of naturally permanent features—trees, hills—to blur as if they too are transitory. Surrounded by the leafless veins of winter trees at Sceaux, a statue contemplates a shrunken pool of image-water only a few feet away. It may be eternally beyond reach, but latent in the scene is the knowledge that in no time at all (a year’s worth of seasons in a day, remember) the pool will fill up again and the trees return to full leaf like a picture that has not yet finished developing (and which will never be permanently fixed). Hovering over the landlocked equivalent of deep oceanic time, statues by the lake at Saint-Cloud are faced with dark forebodings of their own eventual dissolution, when they will exist only as we see them now, as photographs.©

This essay was originally published in the catalog for the exhibition Eugène Atget: Paris, 1898-1924; the text has been slightly edited for the pages of Aperture. The show was inaugurated last spring at the Fundación Mapfre, Madrid, and traveled to the Nederlands Fotomuseum in Rotterdam. It will be presented in Paris at the Musée Carnavalet, April 18-July 25, 2012, and subsequently at the Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney, August 24November 4, 2012.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Work And Process

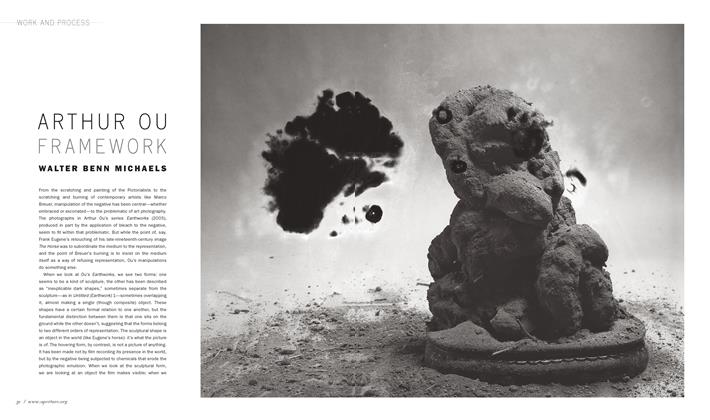

Work And ProcessArthur Ou Framework

Spring 2012 By Walter Benn Michaels -

Witness

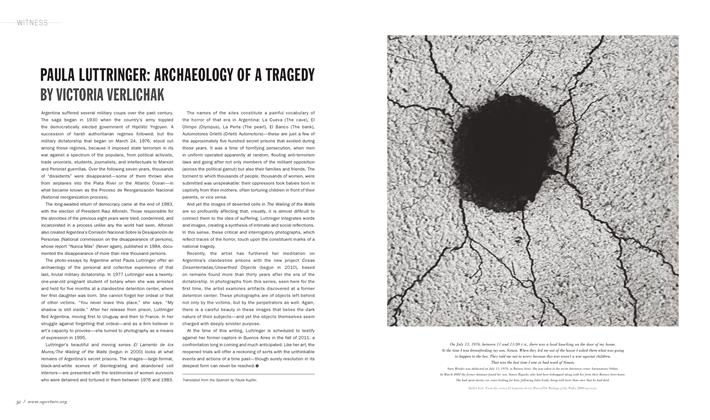

WitnessPaula Luttringer: Archaeology Of A Tragedy

Spring 2012 By Victoria Verlichak -

Portfolio

PortfolioLieko Shiga Out Of A Crevasse: The Days After The Tsunami

Spring 2012 By Mariko Takeuchi -

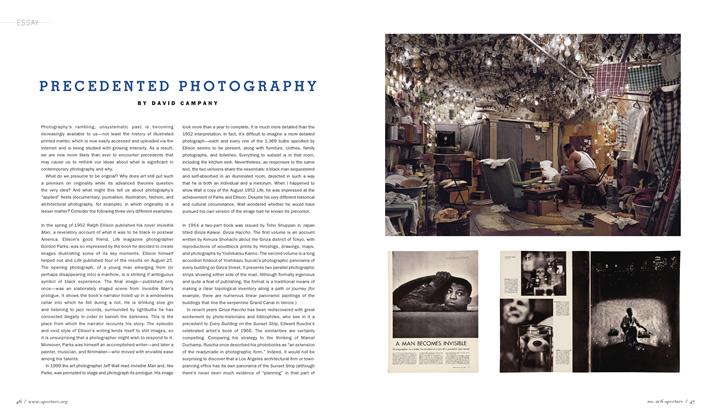

Essay

EssayPrecedented Photography

Spring 2012 By David Campany -

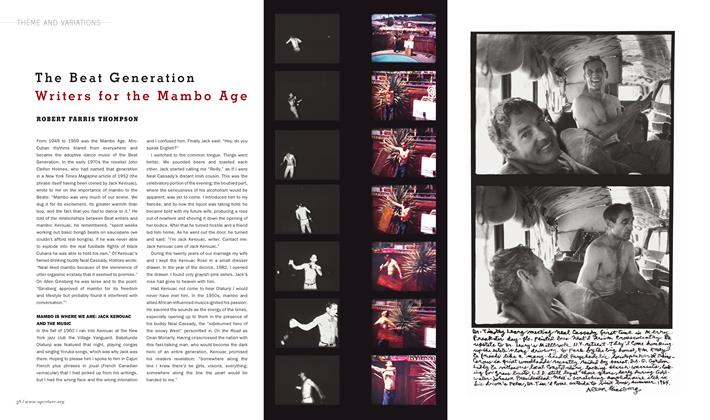

Theme And Variations

Theme And VariationsThe Beat Generation Writers For The Mambo Age

Spring 2012 By Robert Farris Thompson -

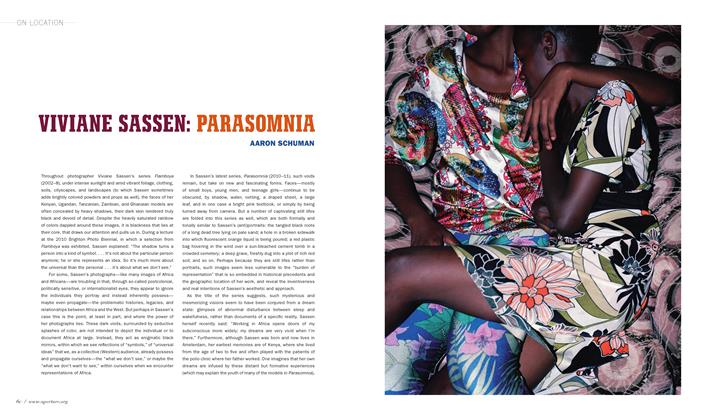

On Location

On LocationViviane Sassen: Parasomnia

Spring 2012 By Aaron Schuman

Subscribers can unlock every article Aperture has ever published Subscribe Now

Geoff Dyer

-

Books

BooksAdam Bartos Boulevard

Fall 2006 By Geoff Dyer -

Books

BooksUnseen Uk: A Book Of Photographs By The People At The Royal Mail

Spring 2007 By Geoff Dyer -

The Anxiety Of Images

The Anxiety Of ImagesGeoff Dyer

Fall 2011 By Geoff Dyer -

Redux

ReduxD.H. Lawrence's "Art And Morality"

Summer 2014 By Geoff Dyer -

On Portraits

On PortraitsGarry Winogrand

Spring 2018 By Geoff Dyer -

Front

FrontCurriculum

Fall 2021 By Geoff Dyer

Archive

-

Archive

ArchiveRussian Pictorialism: The Good, The Pure, And The Everlasting

Spring 2003 By Evgeny Berezner -

Archive

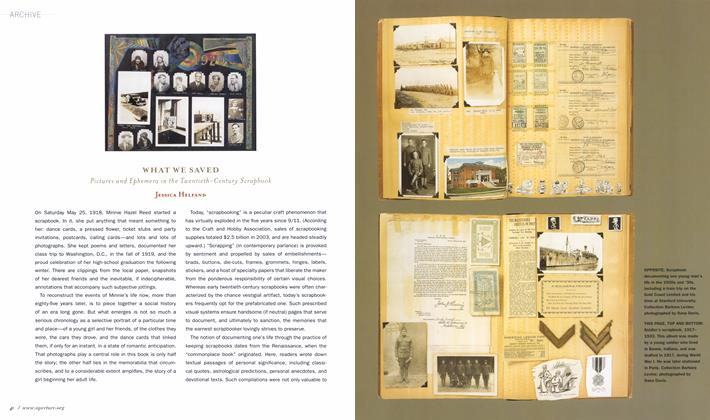

ArchiveWhat We Saved

Summer 2006 By Jessica Helfand -

Archive

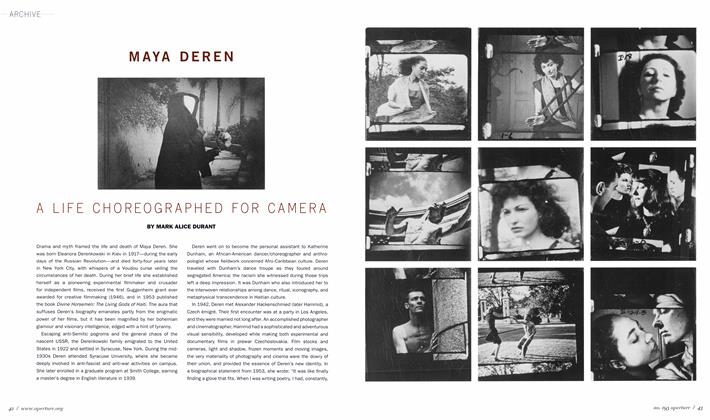

ArchiveMaya Deren

Summer 2009 By Mark Alice Durant -

Archive

ArchiveOn The Art Of Lee Miller

Spring 2007 By Mark Haworth-Booth -

Archive

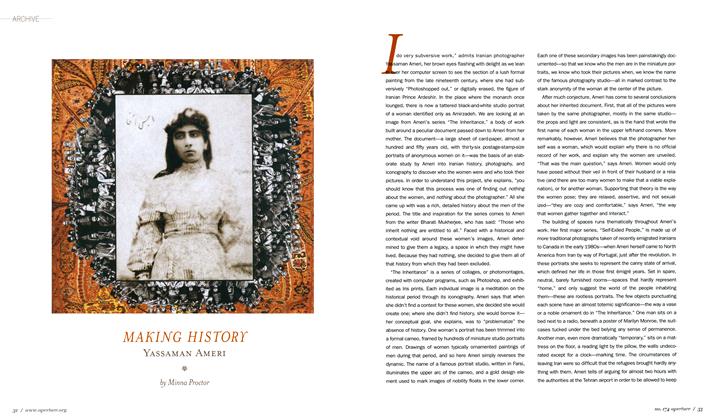

ArchiveMaking History Yassaman Ameri

Spring 2004 By Minna Proctor -

Archive

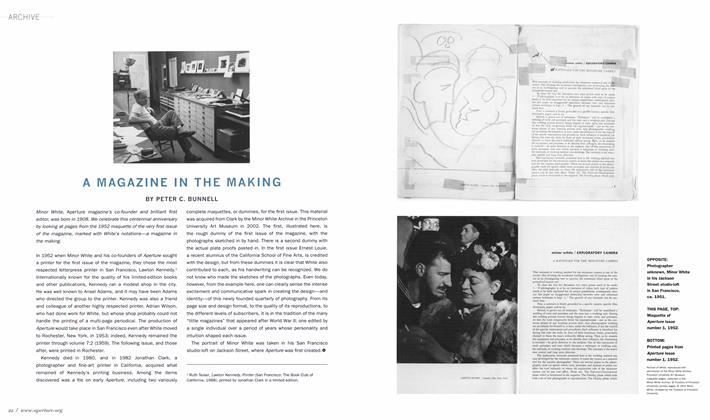

ArchiveA Magazine In The Making

Winter 2008 By Peter C. Bunnell