YAMAHA SRX600

CYCLE WORLD TEST

THE THUMPER RETURNS TO AMERICA

WHY," ASKED THE MARketing expert from another motorcycle company, "would Yamaha do such a thing?"

He paused. “Big Singles haven’t sold in the U.S. for over 20 years. Why bring one in now? Who is Yamaha trying to reach with the SRX?”

Those doubts aren’t surprising; the recent past has been littered with big, street-going Singles, machines that cluttered showrooms and warehouses. Honda’s FT500 Ascot, Suzuki’s GN400, and. after a fairly successful introductory year, Yamaha’s own SR500 all ended up on the non-current lists, finally to be pushed out dealers’ doors with the assistance of big discounts. All have vanished from the U.S. market, and that sad history confronts Yamaha with its new four-stroke thumper, the SRX600. Who indeed might want such a machine?

Motorcycling romantics, is the first, most obvious guess. There are still riders out there who remember the sound and look of English thumpers, the ageless BSAs and Matchlesses and Nortons. There are others who remember the smaller

Italian Singles, the Ducatis and Patillas, with their curvaceous gas tanks and ear-drilling exhaust notes. Perhaps Yamaha hopes to tap those memories and the nostalgia they in-

voke by offering a replica of those classic machines.

But that’s too simple; nostalgia only goes so far in explaining what Yamaha intends with the SRX. Take the engine, for instance. While it’s eminently single, this thumper is cer-

Itainly a slightly no antique. modified Instead, version it’s of the simply latest duaí-purpose XT600 engine, a twin-carbureted, single-overheadcam, four-valve design that concedes nothing to the past,

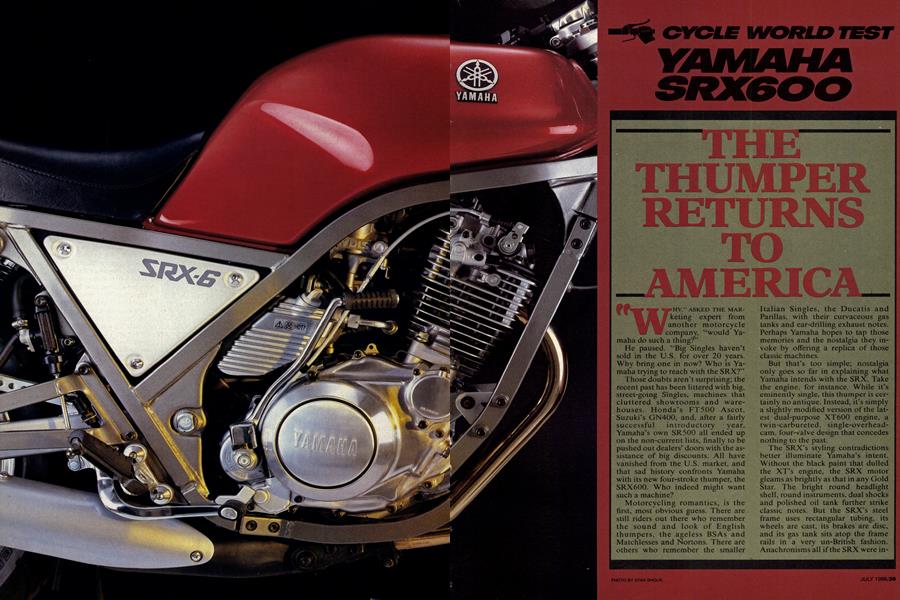

The SRX’s styling contradictions better illuminate Yamaha’s intent, Without the black paint that dulled the XT’s engine, the SRX motor gleams as brightly as that in any Gold Star. The bright round headlight shell, round instruments, dual shocks and polished oil tank further strike classic notes. But the SRX’s steel frame uses rectangular tubing, its wheels are cast, its brakes are disc, and its gas tank sits atop the frame rails in a very un-British fashion, Anachronisms all if the SRX were intended as a true retro-bike; instead, the SRX offers only gentle hints of the past, while being thoroughly planted in the present.

That’s exactly what Yamaha wants. To understand why, you have to know that the SRX was not designed for America. The Japanese home market was its main target, with Europe a secondary concern. The U.S. surely figured last. In Japan, Yamaha already had its retrobike; The original SR500 (still available there) had increasingly taken on the look of classic thumpers, and sold well. By adding the SRX to its line, Yamaha made room for the SR to further regress, to inherit spoked wheels and a drum front brake from an imagined past.

So the SR, in its latest guise, is a bike for Japanese romantics, who ride it wearing waxed cotton reproductions of classic British riding gear. The SRX complements it by offering only a subtle whiff of that romance, and providing comforts and performance to compete with present-day motorcycles—at least that is Yamaha’s plan.

So who might the SRX appeal to? First, its styling seems to strike a chord with those of us who grew up with 1960s motorcycles, either British or Italian. Viewed with those machines as a background, the SRX’s proportions are classic, its details resonant without being affected.

Beyond styling, the SRX appeals to anyone who likes lightweight, compact motorcycles. It carries its 363 pounds low, and, with a 54.5inch wheelbase, feels small. Its footpegs are mounted relatively high and under the rider, a position that is sporting without being cramped. The clip-on-style handlebars lean the rider forward, but not excessively so. The narrow gas tank almost sensuously molds itself to the rider; other motorcycles should fit so well.

An SRX rider finds himself engaged far beyond simply fitting well; even starting the SRX is an experience, one that was described by an enthusiastic test in a Japanese magazine as a “ceremonial action between man and machine.’’ In American, that means the SRX has to be kickstarted.

Historically, kickstarting a 600cc four-stroke Single has been a ceremony more to be endured than enjoyed; but Yamaha has removed most of the pain with an automatic decompressor, a good ignition and precise carburetion. Generally, the SRX starts from cold after one to two stout kicks; when the engine is warm, one more half-hearted effort will usually suffice. But as with any other thumper, there comes the time when the SRX’s engine stalls before it’s completely up to operating temperature, and restarting requires some unguessable intermediate choke position. Then the SRX can try your patience, requiring a half-dozen kicks (or more) to re-fire. If you allow it to stall at a traffic light, with the inevitable line of cars behind, other ceremonies may come to mind: ritual machine sacrifice (mechanocide), for instance. Such occasions are rare with the SRX, but do occur. Sooner or later, even the most staunch proponent of kickstarting will have at least a fleeting wish that the SRX were fitted with an electric starter.

As kickstarting the SRX is only a reminder of what older thumpers were about, other engine characteristics have been similarly muted, most noticeably the exhaust note. At idle it’s an almost inaudible burble, and at higher speeds it has all the charm of a somewhat flatulent Briggs and Stratton. It’s not an exhaust note to stir even the most romantic soul.

But then again, the SRX’s engine fails to stir in some ways that can be better appreciated. An SRX rider might notice some vibration, but a gear-driven counterbalancer has dulled the shaking until it’s no bother. At cruising speeds only a pleasant rumble can be felt in the pegs and grips. Not until near the 7000-rpm redline does vibration intrude, buzzing all surfaces in contact with the rider. But even then it serves more as notice that it’s time to shift rather than as a real annoyance.

And shifting is something the SRX rider had better enjoy. While thumpers are considered lazy motorcycles that can torqu.e along in top gear, current reality is somewhat different. To improve acceleration, the SRX has less flywheel than classic thumpers; and the power pulsations characteristic of a Single, undamped by great flywheel mass, cause driveline snatch in the SRX at engine speeds below 2400 rpm in top gear. That means only 65 percent of the engine’s rev range is usable in top gear; most Fours have available at least 80 percent of the range, and some have even more. So forget about shifting up to top around town; the SRX will insist upon no higher gear than fourth unless it’s doing 35 mph or better.

In the city, the SRX’s acceleration is acceptable, and then some. It clearly has a leg up on most of its thumper predecessors, but above 65 mph, the acceleration noticeably slackens. If a rider is to extract the best from the SRX on a twisty road with medium-fast corners, the shifter must again be exercised, switching between third and fourth gears. So, the SRX definitely is not for someone who doesn’t like to shift.

In exchange for that left-foot workout, the SRX rewards with exceptional handling that has a decidedly unmodern feel. The combination of light weight, an 18-inch front wheel, narrow bars, a rigid chassis and conservative steering geometry have produced a motorcycle that can turn quickly, but with steering effort relatively higher than on most current sportbikes. Offsetting the comparatively high effort is great stability, and a feeling that nothing could deflect the SRX from its line. Ground clearance is good, as well, though the sidestand drags when turning left before the tires run out of traction.

Good suspension adds to the SRX’s backroad prowess. The ride, both front and rear, is just slightly on the firm side, yet very compliant. Even choppy freeways, with expansion joints that can shake a rider’s kidneys out if he’s on certain stiffly sprung sportbikes, fail to disturb the SRX. Neither, as on some other Yamahas, has this front-fork compliance resulted in excessive dive during braking; the SRX’s seemingly simple suspension works in a way that belies its specifications.

Actually, anyone who appreciates a motorcycle that functions well can appreciate the SRX. Outside of its single-cylinder engine peculiarities, almost everything it does, it does well. All controls, including clutch, shifter and brakes, work smoothly with good feedback. The throttle is light, and as mentioned, the handling and suspension are excellent.

There are other attractions, as well. Maintenance is simple, with threaded adjusters for the four valves, and little else to mess with. The ignition shows its dirt-bike heritage in not requiring a battery; the SRX can be started even if the battery is stone-dead. The SRX’s fuel economy is typical for a thumper, approaching 60 mpg and giving it a range well over 200 miles. And the seat and riding position are comfortable enough for all that range to be used at one sitting.

While there’s plenty to like about the SRX, it remains a peculiar bike, different from any other currently on sale in this country, handicapped by the lack of an electric starter, and blessed with competence in most everything else, if not with speed.

Who might want such a motorcycle? Almost anyone could enjoy it. But only time will tell if anyone will buy it.

YAMAHA SRX600

$2599

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Departments

DepartmentsEditorial

July 1986 By Paul Dean -

Letters

LettersLetters

July 1986 -

Roundup

RoundupSlowing the Insurance Liability Crisis

July 1986 By Camron E. Bussard -

Roundup

RoundupLetter From Japan

July 1986 By Koichi Hirose -

Roundup

RoundupLetter From Europe

July 1986 By Alan Cathcart -

Evaluation

EvaluationVetter Flagman Hi-Tech Tankbag

July 1986