When the photographer Gregory Crewdson was growing up, in Park Slope, his psychoanalyst father’s office was in the basement of the family’s brownstone. Crewdson and his siblings were told to ignore the stream of grown-ups who marched hourly through the house, even if they were outside, playing on the stoop, and wound up face-to-face with one. But sometimes he’d lie on the wide planks of the living-room floor and wonder about conversations below. “I always tried to imagine what I heard and make pictures out of it in my mind,” Crewdson says. He is 46 now, with two kids of his own and a longish wave of graying hair. He’s recently begun seeing a therapist whose office is directly below his Greenwich Village studio, and yes, they’ve discussed what that means.

“But I could never really hear anything,” he says of his childhood eavesdropping. “All I knew was that it was a secret and that it was forbidden.” He laughs. “And there you have it. There’s my work in a nutshell.”

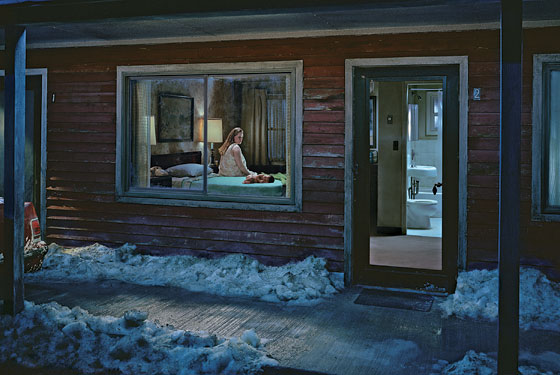

Crewdson produces large-scale, elaborately constructed photographs taken in and around the town of Pittsfield, Massachusetts, where the Crewdson family has forever had a small log cabin in the woods. He has just completed a series of 32 new photographs called “Beneath the Roses,” some of which will be shown at the Luhring Augustine gallery beginning this week. Thematically, “Beneath the Roses” is a lot like “Twilight,” the series that launched Crewdson into the photographic big (up to six-figures-a-picture) leagues. In both, ordinary people in ordinary places are surreally and beautifully lit, and there’s an unease to everything, a suggestion of something lurking just outside, underneath, or possibly within the frame. Even at their most lush, Crewdson photographs are epically lonely. “There are two possible interpretations,” he says of his work. “One is the possibility of impossibility and two is the impossibility of possibility. I know there’s a sadness in my pictures. There’s this want to connect to something larger, and then the impossibility of doing so.”

Crewdson’s method of photography is highly unusual; he has not taken a picture all by himself for the past ten years, save the occasional snapshot of his kids. He works with a crew of about 40: lighting, set, production designers, and even a director of photography. For “Beneath the Roses,” there was one crew that made snow, another for rain. Crewdson is pains-takingly specific with them, personally directing the scattering of dirty, gritty snow, for example, along the side of a road.

As much as the theme of alienation persists in Crewdson’s work, so, too, does the location: Pittsfield. He is a city boy totally uninterested in the city as artistic subject. “You have to be able to see it all new every time,” Crewdson says of situating his work in one small place only, “and it’s excruciating, but it’s joyful. I feel like the artists I admire most are artists aligned with a particular geography, like Cheever, or Edward Hopper, or even Norman Rockwell, who worked in the next town over from me. And I like the separation. When I go up there, I’m going to work.” Crewdson no longer vacations in the Berkshires; he takes his family to Montauk instead.

His process goes like this: He starts by driving around and around familiar old Pittsfield and its environs until something familiar feels unique. He stops, he registers it all, and calls in his team. Then he frames, with his hands, the shot. “He tells me the physical focus of a picture,” says Rick Sands, the director of photography who’s been with him for eleven years, “and the emotional focus as well. And then we get to work.”

“Beneath the Roses” consists of four separate productions. Three were on location and are concerned primarily with broad landscapes, a somewhat new direction for Crewdson. The other was in a soundstage on which Crewdson and Co. constructed elaborate interiors.

It’s not an easy undertaking: The snow nearly killed him it was so hard, and a number of houses were demolished or set on fire for the photographs. But when all that effort comes together in one picture, “It’s the most beautiful moment for me,” Crewdson says. “Everything’s aligned in the world at that moment. The world makes sense. Order. Perfection even. It makes me weep.”

It is also an extraordinarily expensive way to make art. The productions are under-written by the three galleries that represent Crewdson, but he won’t get specific about what it cost to produce these 32 images, saying only that his line producer is quite strict. Still, any suggestion that Wall Street’s travails may take a bite out of the contemporary-art-market mania turns him pale: “Of course I worry about that!”

Because Crewdson’s method is so cinematic, and he has close relationships with many filmmakers—Noah Baumbach and Wes Anderson, to name two (he freely admits his childhood brownstone is very Baumbachian in tone)—and because the photographs have a decidedly narrative feel, almost as if they were film stills, it would seem a logical next step for him to direct a movie. He doesn’t agree. “I think in terms of single images,” he says. “My work is profoundly connected to that tradition. I really don’t know what happens before or after an image. I really have no clue.”

The last time Crewdson shot anything himself was when his first marriage had fallen apart, a decade ago, and he’d retreated, of course, to that cabin in the woods and begun to photograph fireflies. He put the images away after that painful summer but recently reopened the box. “They couldn’t be more different from the way I’m making pictures now because they are so economical, so simple, but at the same time they’re very connected to what I do. They use light as a way of telling a story, and a moment of wonder. I guess my point is that you can’t really get away from yourself ever. Every artist has a story to tell. The form of the story changes, but the core obsessions are still there.”