Subscribe to Our Newsletter

Gleaming the Cube

Often misperceived as second banana to a certain famous Spaniard, Georges Braque co-invented Cubism but didn’t stop there.

Georges Braque, Grand intérieur à la palette (Large Interior with Palette), 1942, oil and sand on canvas.

Featured Images: (Click to Enlarge)

- Georges Braque, Fishing Boats, 1909, oil on canvas;

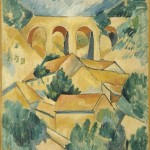

- Georges Braque, Le viaduct de l’Estaque (Estaque Viaduct), 1908, oil on canvas;

- Portrait of Georges Braque.

- Georges Braque, Grand Nu (Great Nude), 1907–1908, oil on canvas;

- Georges Braque, Grand intérieur à la palette (Large Interior with Palette), 1942, oil and sand on canvas.

In August 1914, as soon as France declared war against Germany and Austria-Hungary, Georges Braque enlisted in the army. The 32-year-old painter had plenty of martial spirit. Well known as an amateur pugilist, he was already the veteran of a bloody artistic war—the fight to make the world safe for Cubism.

During a period of feverishly intense experimentation in between 1908 and 1912, he and Pablo Picasso had co-invented a new way of rendering the world on canvas or paper, an optically rigorous decomposition of an form into its geometric units that effectively showed it from many points of view simultaneously. The four years the artists spent together developing and perfecting this insight, Braque later recalled, were “like being roped together on a mountain.” In the heady atmosphere up there, the two artists not only painted and drew together constantly but talked and talked, often in a strange, invented language of jokes and puns that was the linguistic counterpart of a Cubist image. As Braque put it, “The things Picasso and I said to one another during those years will never be said again, and even if they were, no one would understand them.”

Dressed in a drab uniform instead of his usual offbeat bohemian garb, Braque boarded a train bound for the Western Front. His friend Guillaume Apollinaire, the poet and Cubism’s great propagandist, had already joined up. Braque’s combat service would not last long. In May 1915, during the Second Battle of Artois, he received a severe head wound that required trepanation (a form of surgery involving cutting a hole in the skull), and was invalided home. It would be almost two years before he picked up a brush again, and while he continued painting right up until his death in 1963, potted biographies of Braque tend to trail off after 1916, as if most of his artistic vigor had leaked out of the hole in his head. But although World War I definitely constitutes a hiatus in his career, Braque was by no means a diminished artist. A complete overview of his work makes it clear that he continued to work out the implications of the Cubist insight over the next five decades without ever becoming stuck in a rut, while taking a completely different attitude and direction from Picasso’s.

Just such an overview is actually available to American audiences now, at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston. Starting on February 13 and running through May 11, the museum will be the sole U.S. venue for “Georges Braque: A Retrospective,” a 75-work exhibition that originated at the Grand Palais in Paris as a commemoration of the 50th anniversary of the artist’s death (the American edition of the show contains somewhat fewer works than the French, which was curated by Brigitte Léal from holdings of the Centre Pompidou supplemented by a wide range of loans). In this country, it will be the first full-scale retrospective of Braque since the Guggenheim’s in 1988. Alison de Lima Greene, the MFAH curator who organized the Houston show, says it’s time for Braque to be better understood, particularly in regard to his late work. “There’s a little bit of reinterpretation going on with this show,” she says. There’s always this insistence that Braque was a great Cubist artist and nothing more. It’s a revelation to look seriously at the very late work one more time and realize that something quite beautiful and mysterious is happening there. For us, if not for the artist, there’s still something unresolved, something to reckon with.”

For those most familiar with Braque’s pre-World War I Cubist works, with their densely packed, crystalline compositions and relatively monochromatic palettes, the late works will come as a surprise. Light and airy and suffused with color, they deploy simple, bold forms with little internal detail. They often depict birds in flight. In L’oiseau noir et l’oiseau blanc (Black Bird and White Bird), an oil on canvas from 1960, a black bird and a white bird almost touch heads, against backgrounds of, respectively, pink and yellow. Looking straight at the picture frame, the viewer might well be staring straight up into the sky. A Tire d’aile (A Flurry of Wings), from 1956–61, shows a black bird, neck extended, flying over (or past) a black shape, while a similar white bird flies within a smaller white-bordered frame at the lower left of the painting. Paintings like these convey an almost Buddhistic sense of letting go, a release from artistic struggle into pure contemplation. Like his birds, Braque seems to be taking wing. A mid-period work, Grand intérieur à la palette (Large Interior With Palette) from 1942, is a still life, one of Cubism’s favored genres. The multiple viewpoints are still here, but instead of using tessellated planes to fractionate space, Braque has achieved his effect with contrasting color zones—the preponderance of browns and tans offset by rich green, orange, lemon yellow, and white—divided up by smoothly curving lines.

The persistence of subject matter is part of Braque’s identity. Late in life he told an interviewer, “I realize that I paint the same anonymous things today that I did when I started out, objects that touched me, without my being aware of it, and that have pursued me from then right up until this final realization.” His earliest works are landscapes. What inspired him to see Cubistically was not the Demoiselles d’Avignon (1907) drying in Picasso’s studio, but Cézanne’s landscapes and still lifes, with their incipient tendency to combine different spaces in one composition. Braque’s first period is called Fauvist, and in 1906 and 1907 André Derain was his idol. The landscapes Braque painted at Estaques, some of which are on view at the MFAH, render the port with its houses and boats set against the hills in acid-rainbow hues, sometimes with short, staccato brushstrokes that suggest a sort of plump pointillism. Trained at the Ecole des Beaux-Arts at Le Havre and at the Académie Humbert in Paris, Braque broke with tradition when he saw the work of Derain, Matisse, and Vlaminck at the 1905 Salon d’automne, which unleashed Fauvism on the world. But in a sense he was fulfilling tradition—family tradition. As the son and grandson of house painters, he was and continued to be preoccupied with questions of design, the way colors and forms sit on a surface, which happens to be, when you get down to it, the central concern of modernism.

Cubism entails taking three-dimensional space and unfolding it out over a flat surface, to expose the whole thing to view, not just what the eye sees at once, unaided. The word “Cubism” can be misleading. Picasso and Braque didn’t use it when they were creating the style; it was actually coined by a hostile critic, Louis Vauxcelles, in reference to Braque’s 1908 landscapes at Estaques, which he called “bizarreries cubiques” (cubical oddities). While Cubism can be understood as the ultimate visual aid, to the uninitiated, like Vauxcelles, it can be confusing to the eye.

Among the astounding Cubist paintings in the Houston show is Soda, from 1912 (reproduced on page 22), which examines a soda bottle from every imaginable perspective, yielding a kaleidoscopic, fly’s-eye view in which the label, reading “Soda,” is at first the only raft of visual comfort that the beholder can grab onto. Studying it further, one realizes that it is a classic case of “center everywhere, circumference nowhere” (in the words of the Renaissance theologian Nicholas of Cusa). Except that in this case there is a circumference, in that the canvas is circular, perhaps suggesting a bottle seen from below. Braque made several circular or oval paintings during this period, of which de Lima Greene says, “I think he liked them for their ability to cut off all that was extraneous. It also had to do with his awareness of decorative painting. In any French palace or haute-bourgeois house there were paintings enclosed in decorative panels—for example, portraits in ovals. And then there’s the tabletop, the classic setting for a still life. The tabletop becomes your mirror as a viewer.”

Other than Soda, the Houston show features about 30 paintings from the key years 1908–14, including Le port (Fishing Boats), from 1908–09, and Compotier et cartes (Fruit Dish and Cards), from 1913. In the former, the landscape becomes Cubist; in the latter, we move into the phase of “synthetic Cubism” (as contrasted with the earlier, “analytic” Cubism), in which the abstraction takes us one step further away from the original subject being represented and color starts to re-enter the picture. Another feature of synthetic Cubism is the use of collage. By 1912 Braque was further interrupting the picture plane by adhering little strips of printed paper to it, which he called “papiers collés.” In Compotier et verre (Fruit Dish and Glass), from 1912, he glued faux-wood-finish paper on top of drawing paper and made the wood grain blend with the pencil lines he drew.

There has been a little argument as to whether Braque can be given full credit for inventing collage or whether he should share it with Picasso. “The usual accepted wisdom,” says de Lima Greene, “is that Braque was able to make that intuitive leap because of his father’s work in decoration and trompe l’oeil framing. But it’s much more interesting to say not who invented it but what each artist chose to do with it. What you get in Braque that you don’t see in Picasso is the emphasis on the materiality of what he was using. He would even use sawdust or sand to give different textures. Picasso was very witty with his use of sources, but Braque like to take advantage of the materials as material, and also to defeat them. Sometimes an element in looks like a collage element but isn’t, or vice versa.”

Picasso, as everyone knows, went on to express himself relentlessly and dynamically, changing all the time, searching for new subjects but returning always to the figure and portraiture. Braque remained focused more on what de Lima Greene calls “the architectural sense of space,” which he developed through continuing exploration of the still life. “More than Picasso,” adds de Lima Greene, “Braque was a nuanced colorist, and in the late ’teens he created color harmonies that he teased out and tested over the rest of his career.” And he always stayed faithful to his materials, his pigments and textures, which in a very real sense were the “anonymous things” that pursued him down the years.