The “Greatest Storms on Earth” Part IV

This is a continuation of a series on the history of hurricanes in our area. If you missed part, you can find it online at coastalbreezenews.com under Tales told Twice archives.

1935

“The wind, it was tremendous. You couldn’t hear. And the pressure inside the packing house was so much greater than what was outside that the windows blew out. My nephew was pulled right out of my arms. My mother went, too. I never saw them again. I managed to grab hold of the doorway. I felt the house start to rises up, like it was going to blow away, so I went into the storm.” Bernard Russell, age 17 Labor Day Hurricane 1935, 50 members of the Russell family died that night trying to ride out the storm at a point 12 feet above sea level.

A Category 5 hurricane is one that is rated over 156 mph, and 156 wind is not, as one would think, just ten times stronger than a 15.6 mph wind; but as wind speeds grow exponentially, it is actually a hundred times stronger. A hurricane of this immense power will have a very small eye with fast spinning winds, very low pressure, and usually will push a large tidal wave. The energy released in a twenty-four hour period by a tropical hurricane is as much energy as nations like Britain or France use in a full year. A Category 5 hurricane that is moving slowly forward, causing complete devastation beneath, is the worst situation possible.

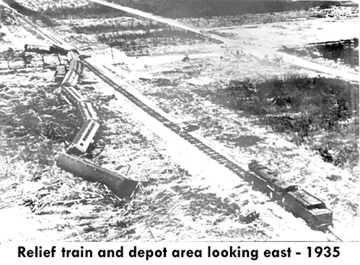

September 2, 1935 – the “Labor Day Hurricane of 1935” was such a storm. It had a small, only eight-mile diameter eye, and traveled at a speed of 10 mph. If there was a blessing in this storm it was that the eye was only over Florida landmass for less than one hour, as the storm’s path took it over the upper Keys and then tracked through Florida Bay, staying just off the Southwest Florida coast as it headed northward.

As was the norm at the time, there was little notice given of either the storm strength or possible target. In fact, the day before it hit, the Weather Bureau described it as “shifting gales and probably winds of hurricane force” and projected its path to be more to the west, missing Florida. Fortunately, the Coast Guard dropped warnings in cardboard ice cream boxes to the fishing fleets along the coast and the Cuban officials warned that the storm was getting stronger. No one had any idea that it would, or could, intensify so quickly. It was

reported that only 30 hours before hitting Florida the storm was not even at hurricane strength!

The survivors could not even describe the force of the winds and all wind instruments were destroyed, leaving experts to try to judge just how bad this storm was. No one doubts it came ashore as a Category 5, and engineers reviewing the damage believe the wind speed in the upper right quadrant, normally the most destructive portion of a hurricane, was 150-200 mph over a 15-mile range. Others believe that the winds were closer to 250 mph. No recorded hurricane in history had ever approached this power. Barometers at the time recorded readings below 27.00 inches, unheard of, leading one expert to note that pressure gradients like this are only exceeded in tornadoes.

There was more about this hurricane that was unusual: survivors had to endure not only the deafening roar of the wind, but that night was especially dark and they saw flashes in the sky “like millions of fireflies.” It is believed that the high winds lifted sand particles into the air that generated static electricity creating small flashes. The tidal surge was unreal, the hurricane was pushing a wall of water 17 to 18 feet high in front of it, nothing could withstand the flood. Bridges, roads, buildings, the Flagler-built $27 million dollar Miami-Key West railroad was gone, and of the 61 buildings on Matecumbe Key, where the town of Islamorada is located, only one building was left standing, and trees were cut off at their bases leaving the island barren.

That anyone survived the only Category 5 storm to ever hit Florida is remarkable. The smart ones left and, upon returning, found their “hurricane proof” shelters, built high and strong as safe houses, knocked down by the storm. Those who stayed and managed to survive were in shock. Ernest Hemingway, who rushed from Key West to help, vowed never to write about what he had seen, but in one private letter written to a friend he described the scene ? it is far too graphic to reprint here. We know that some bodies were unrecognizable. They had lost their features and clothing in the sand blasts; others had drowned; some were decapitated by flying tin roofs, and impaled by limbs; others were found in the tops of fallen trees where they had tried to climb to their safety; and there were many more horror stories best left unsaid.

“He has some cuts and bruises, but it is what he does not have that sends a spear through her heart. Her husband is not holding their baby, Frank.” All they can do is gingerly cling to each other, their sobs obliterated by the wind, their tears washed away by the wind. Thomas Knowles, in his book on the 1935 Hurricane, Category Five.

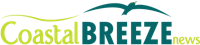

Hemingway’s outrage for what he saw as inept government handling of the situation was expressed in a magazine article he wrote: “Who Killed our Vets?” published on September 17th. The U.S. Government had brought WWI veterans to the Keys to work on the construction of the overseas highway, many of whom had previously marched on Washington protesting the non-payment of bonus money they felt they were owed, and because of the depression was badly needed. Members of the “Bonus Army” and their families were put to work by the government in the Keys and, while a rescue train was sent from Miami at around 4 p.m. the day of the storm to pick them up, it arrived around 8:23 p.m., the time the hurricane hit (the actual time determined later as all clocks stopped). Every boxcar was knocked off the tracks and only the locomotive remained. The engineer later said, “There were times we were unable to breathe due to water breaking over the locomotive.” Of the people living in the upper Keys, more than 400 died and, of those, approximately half were veterans or their families.

Meanwhile, the Labor Day Hurricane of 1935, after battering the Keys, continued through Florida Bay, eliminating any trace of Fort Poinsett, a U.S. Army fort located at Cape Sable during the Seminole Indian Wars. After taking down many of the trees in the southern coastal Everglades, it then passed about 25 miles off the coast of southwest Florida. Ted Smallwood, a faithful observer of hurricanes, reported that in Chokoloskee they had about two feet of water and lots of wind. In Naples the winds were recorded at 115 mph. Thankfully, as the hurricane followed the coastline north, it weakened so that when it again came ashore in Cedar Key in northern Florida, it was only a Category 2 storm.

Dry conditions after the hurricane, along with the fallen trees and dead underbrush, caused immense fires in the Everglades. Many of Florida’s native mahogany trees, known as Madeira trees, burned, with some being up to four feet in diameter and 40 feet high, leaving so few behind that there were not enough to propagate and they, too, eventually died out.

A congressional investigation resulted in the bureaucratic conclusion that the tidal wave was unexpected and it was impossible to anticipate the hurricane with sufficient time to ensure safety for those concerned. However, the country had had

enough of disasters in Florida and officials got the message that hurricane forecasting, public education, and advanced warnings were needed and essential.

1940s

In 1943 the Weather Bureau teamed up with forecasters from the Navy and Air Force and, at their Miami office, added new technologies like radar, and reconnaissance flights, with this office becoming the precursor to the National Hurricane Center. The progress was more than timely as, between 1941 and 1950, Florida was hit by twelve hurricanes in a ten year period. Of the twelve, six impacted southwest Florida. The first, in 1941, was a “backdoor” hurricane, meaning it came not from the Gulf side but, instead, crossed the state from the east coast. As a Category 2, it did minor damage with some flooding in Everglades City and Chokoloskee. The 1944 Hurricane crossed the Dry Tortugas and passed Collier County to the west on October 19th. It caused a heavy storm surge in Naples with tides up to twelve feet above normal and with a 4.5 feet above mean high tide recorded in Chokoloskee. The salt water killed all of the guava trees, and winds were recorded at 115 mph in Naples. The Coast Guard was called in to help residents in the flooded areas.

In 1945 another “back door” Hurricane passed to the west of Collier County heading north up the center of the state as a Category 4 storm with 125 mph winds recorded in Naples. Two years later the eye of the September 1947 Category 4 Hurricane was over Naples for approximately one hour and dumped eight inches of rain, along with a six foot storm surge and over 100 mph winds. A month later, in October of 1947, a second hurricane flooded Miami and most of the Tamiami Trail to Everglades City, prompting the construction of the levees one now sees when driving the Trail. Finally, on September 21, 1948, a Hurricane came up from the south with 115 mph wind, entering Florida near Everglades City, tearing off the porch to Charles McKinney’s (the “Sage of Chokoloskee”) house, destroying another house, and pushing a four-foot storm surge.

The 1940s were the heaviest period of hurricanes in the 20th century and it was a relief the decade was over. South Florida would get a ten year reprieve with no activity in the 1950s. It was acknowledged by the press and Floridians that progress was being made and the Weather Bureau’s timely warning system was saving lives.

Craig Woodward moved to Marco Island in 1968 and for many years, Craig has led a history tour of the Island for the Chamber of Commerce’s Leadership Marco program.

Post a comment as Guest

Report

Watch this discussion.

(0) comments

Welcome to the discussion.

Log In

Keep it Clean. Please avoid obscene, vulgar, lewd, racist or sexually-oriented language.

PLEASE TURN OFF YOUR CAPS LOCK.

Don't Threaten. Threats of harming another person will not be tolerated.

Be Truthful. Don't knowingly lie about anyone or anything.

Be Nice. No racism, sexism or any sort of -ism that is degrading to another person.

Be Proactive. Use the 'Report' link on each comment to let us know of abusive posts.

Share with Us. We'd love to hear eyewitness accounts, the history behind an article.