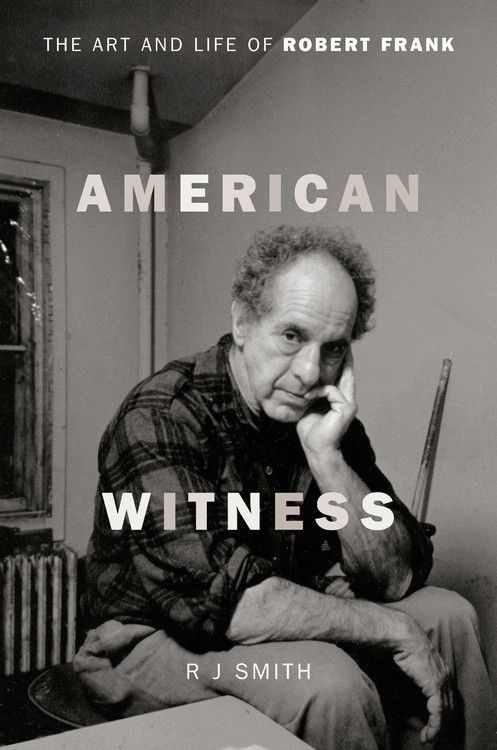

Robert Frank’s favorite picture from his seminal photo book The Americans—published in France in 1958 and then a year later in the U. S.—is of an African-American couple sitting in a San Francisco park, their heads turned in anger toward a stranger invading their privacy. They wish to go unobserved. The same might be said about Frank, as RJ Smith tells it in his brief but well-observed new biography, American Witness: The Art and Life of Robert Frank.

A Swiss Jew who survived World War II and arrived in New York just as the city was becoming the artistic center of the world, Frank was part of a generation burning to break from the conformity of the postwar period. With the help of a Guggenheim grant, and support from Walker Evans ("mon cher professeur"), he spent 1955 and ’56 crisscrossing the country by car—just before Eisenhower’s interstate highway system and Kerouac’s On the Road made such journeys a rite of passage—and occasionally landing in jail. He took more than 27,000 pictures, which he gradually edited down to the 83 that filled The Americans.

The reviews were mixed at first, but its cult would grow to include photographers like Danny Lyon and Ed Ruscha as well as musicians like Patti Smith and Bruce Springsteen. It was recently voted the greatest photo book of all time by a poll of international photographers. Yet Frank himself had already moved on from the medium. “Once respectability and success became a part of it, then it was time to look for a new mistress,” he wrote.

He made dozens of experimental, mostly short films. (Jim Jarmusch and Richard Linklater are fans.) None, however, was more legendary—or notorious—than the seldom-seen Cocksucker Blues, his vérité documentary about the Rolling Stones’ 1972 U.S. tour, which now looks like a template for every grainy handheld music video you’ve ever watched. (Frank also did the cover for their album Exile on Main St.) “It’s hard to have that much money and power and be human,” he said of the Stones, whose lawyers blocked the film’s release.

Frank didn’t abandon photography entirely, however, and produced several photo essays for Esquire. Next year, Steidl will reissue his deeply personal 1972 monograph, The Lines of My Hand, featuring pictures taken in Paris, London, and Peru. But the most arresting images in the book are the ones he took in this country. Like fellow European émigrés Willem de Kooning, Billy Wilder, and Mike Nichols, Robert Frank could see America more clearly than the locals.

This article appears in the November '17 issue of Esquire.