I photograph to find out what something will look like photographed.

For me the true business of photography is to capture a bit of reality (whatever that is) on film…if, later, the reality means something to someone else, so much the better.

—Garry Winogrand

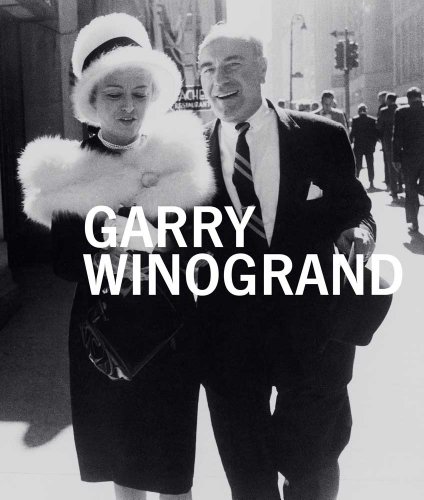

Since the exhibition “Garry Winogrand” debuted at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art in the spring of 2013, the show has proven to be nothing short of a sensation. With subsequent stops in Washington D.C., New York City and Paris, the exhibition was seen by hundreds of thousands of photography lovers from around the world. The body of work on display, numbering several hundred prints (many of which had never been seen before), has shed new light on the man and even on the medium itself.

Although the exhibition is jam-packed—photographs, contact sheets, type-written letters, Guggenheim Fellowship applications, personal correspondences—the exhibition catalogue provides even more insight into the monumental effort required to put everything together. The book is filled with some 460 illustrations, including Winogrand’s most famous images alongside many never-before-seen gems. The texts in the book include an extended introduction by the curator, Leo Rubinfien, as well as excellent essays by Tod Papageorge, Sarah Greenough, Sandra Phillips, as well as several others.

But even after taking in the catalogue’s rich and varied offerings, we found it was still not enough to sate our curiosity. Like Winogrand himself, we found ourselves needing to keep going, to keep searching, to keep learning.

LensCulture assistant editor Alexander Strecker had the opportunity to sit down with the curator of the show, Leo Rubinfien, to find out more. The long conversation offered a variety of wonderful insights: both on the scale of details and what went into the practically Herculean task of curating Winogrand’s life’s work but also on the larger scale, from the universal perspective of “What is photography all about…?”

AS: In the introduction to the exhibition catalogue, you allude to your personal relationship with Winogrand. This seems like a good place to begin our talk…

LR: I was 20 when I first met Garry. We became friends right away. He surrounded himself with younger people. I think their youthful energy pleased him. I was just one in the circle of younger friends and protégés associated with Winogrand: they were Tod Papageorge, Joel Meyerowitz, Lee Friedlander, many others…In all, I knew Garry for about 10 years, until his death.

I was not involved with the first retrospective of Winogrand’s work [in 1988, at MoMA, organized by John Szarkowski] and perhaps in part because of my distance from the exhibition, I was surprised—astonished even—by the essay that Szarkowski wrote in that show’s catalogue. His judgment was that Winogrand had lost his talent and was no good after 1971. And yet the years after 1971 were exactly the ones when I knew him. I couldn’t believe that this man who had had such a large impact on me, and seemed at the height of his powers, was already finished when I met him.

These doubts lingered with me over the years and as time went on, I saw that no one else was addressing the question of what to make of Winogrand’s later years. In the absence of any other effort, I eventually came to work on it myself.

I looked for a while for support for a project that would investigate the late work, but no one seemed interested. Maybe people really thought it was terrible and not worth the effort. Then, thanks to an invitation from Jeffrey Fraenkel [the gallerist and representative of Winogrand’s estate] to produce a compendium of Winogrand’s best work, a platform for exploring his late work appeared. At first, the compendium was intended to be a gallery publication, but very quickly it grew way too large. Ultimately, San Francisco MOMA took the project over, turning it into a retrospective exhibition and book.

I began by looking at Winogrand’s contact sheets, but the late contact sheets immediately led me into the early ones, for comparison, and pretty soon I was examining his career from start to finish. From the beginning, it was clear how much of Winogrand we had all missed. From his early years, there were great photographs that few people, if anyone at all, had ever seen. Maybe Garry had neglected them, maybe he meant to print them but never got around to it, maybe he had printed some but the prints had been lost. Nobody knew, but there was a lot of splendid work there.

At one point Garry had said that what we knew of his work was “just the tip of the iceberg.” And I recall asking him, when he was first living in Texas and had no darkroom of his own, if he was making many prints at that point. He replied, “I don’t need to, I can tell where my work is going by looking at the contact sheets.”

In sum, I ended up looking at around 22,000 rolls of film, which is somewhat under one million photographs. Strangely, that was a good deal more than Garry ever saw of his own work.

AS: What were some of the biggest surprises for you after seeing all these photographs?

LR: First of all, it turned out that what we knew of Winogrand was heavily concentrated between the years 1963 and 1971. And even there, what we knew tended to come from 1967 through 1971. The Winogrand we knew was a limited one.

As to his later work, Szarkowski had said that Winogrand was weakening after he left New York, and in a sense this was true—the ratio of his strong picture to his weak ones was falling—this was perfectly clear. And yet, what was good was still really good. When one added it to the work of his prime years, the 1960s, and also brought in the work that led up to them, the pattern of his development became clear, and with that came a much stronger sense than I’d had before of the meaning of the work.

This led to a further discovery, which was more of an affirmation of something I’d felt before than it was a surprise, really—and this was how much Winogrand was “a student of America,” as he’d described himself. Winogrand has been called many things (both by his supporters and detractors), but he is rarely called a humanist. Yet the more I saw of his pictures, the more that I saw how profoundly he was a poet of American life, who sought continually to understand, as he put it at one point, “who we are are and how we feel.”

AS: In the end, you’ve looked at more of Winogrand’s work than any one person—the early work, the well-known middle work, and the late work. Having looked at so much material, what guided your final selections for the exhibition? Especially in the late work, when Winogrand’s marks became fewer and fewer, what led your thinking? Did you have Garry in mind? Was Szarkowski present in your decisions at all?

LR: Once I was even a bit of the way into the editing, I wasn’t thinking about Szarkowski or Garry. At the very beginning there was a moment when I worried—that maybe there would prove to be nothing of value in Winogrand’s later work, or little. But this was swept aside, really, by pure enthusiasm for what I was seeing, seeing for the first time.

What guided my choices—apart from the simple discovery of strong, little-known or unknown photographs—was the idea that whatever we presented of the late work should be consistent with what came before it in quality and in what it was telling us. As I began to see the large arc of his career, it also came to seem that this arc paralleled that of the psychic life of the Americans during those same years. One has to be careful here not to make too close a connection between the personal and the national, yet the path Winogrand followed seemed in many ways comparable to the path that was followed by great numbers of his countrymen.

While I tried to present Winogrand’s work faithfully, this narrative was certainly, to some degree, imposed by me. Would Garry have found another narrative in his work, had he lived? I’m sure it would have differed in some places, maybe many places. Would he have endorsed this show? It’s impossible to say.

In the end, I think that almost anyone who produces a retrospective show must come to a certain dilemma. On the one hand, you can be loyal to what actually happened, to what the artist intended and believed. On the other, you can be loyal to the future and address yourself to how the artist will be appreciated and perceived in the years to come. This is a choice, and it is not entirely obviously, and yet I felt that if this exhibition were to be effective, if it was going to help us see more deeply into Winogrand than we had, if it was going to help to keep Winogrand vital for younger generations of people, it had to move towards the latter. Inevitably, then, there would be some rewriting, some distortion of pure historical fact.

On a simple level, for example, a significant number of Winogrand’s photographs were made at sports events, but the SFMOMA show presents almost none of them. Should it have included them proportionately? Any time you edit, you choose to include and you choose to exclude, and in doing this you both distort the work, and also give it shape. These choices are necessary, really. The most accurate map of France would be a map the size of France. But that would be map no one could read.

One could seek to maintain Winogrand’s work in an ideally ambiguous and untouched state. But that would be thousands of prints, in the kinds of stacks Winogrand kept in his apartment, impossible to understand. The moment that you attempt to organize those piles of prints, you make something new.

AS: Do you think Winogrand’s photographs “mean” something? Was he trying to communicate some specific ideas?

LR: Photography is fascinating to me because it’s both descriptive and symbolic at the same time. Descriptive because it shows you something that looks like the world and symbolic because the best photographs not only show you the world but also seem to reach beyond it, to speak of something more. A great photograph touches all sorts of things—other perceptions you’ve had, other things you’ve seen or remembered or felt. It’s that density of meaning that fills some photographs with feeling and makes them profound.

Winogrand, especially in public, would often fall back on a rigid argument that photographs were purely descriptive. But once in a while, he would drop this insistence. One time, during a classroom lecture, when he was talking about a certain [Andre] Kertesz photograph, he said that Kertesz had said that this was a photograph of a man looking at his own death. If you ever brought such an idea up in public, he would probably slap you down, and he would never suggest anything like this about a photograph of his own. But in this protected moment with his students, speaking of the work of another photographer he admired, he was willing to suggest that photographs might be not just literal but symbolic.

This being said, Winogrand really did prefer to be led by his photographs and not let ideas or evocative statements get in their way. As he said so often, this was one of his most important qualities—that he would follow his work and let himself be directed by it, insisting that a photographer’s relation to the world is more passive than many photographers want to admit. You come here to one of the most fascinating paradoxes in Winogrand—in that his passivity seems so incongruous with his personal power and force.

Here’s another way to look at this idea: a good photograph is produced from three different sources: nature (or what you happen to see in the world), the machine (since what the machine does is not exactly the same as what the eye sees) and finally the mind and spirit of the person making the pictures.

Now, people involved with photography have long feared that it might be just a mechanical medium. No spirit, no intelligence, all machine. And in fact, this is the case much of the time. A huge number of dull photographs have come to be when too little was present but what the machine did on its own. And as a result, people involved with photography have often come, a bit neurotically, to associate artistry with control.

I think, though, that Winogrand came into photography at a moment when it was possible to insist less upon control. By his time, certain artist-photographers had acquired enough confidence in what they were doing to admit the random, accidental, and unanticipated, and even to find poetry in these qualities, even a greater degree of truth. Where what was uncontrollable about the camera had seemed a deficiency in the past, Winogrand saw it as a virtue.

It’s something like what you find when you listen to a jazz saxophonist. Let’s say that he begins with a score, with music written out in a repeatable sequence—there will still be a great deal of noise, of pure sound coming out of the instrument that isn’t (and can’t be) written down—and that’s a large part of the music itself! That’s the art!

AS: And what do you think people understood from the show? Do you think they “got” the ideas you were hoping to communicate with the exhibition?

LR: I can read reviews, I can talk to a handful of people and hear their reactions—but I can’t really know what any large number of people have thought. Still, it seems that people were very enthusiastic about the show.

In general, they seem to come out of it happy, invigorated. That’s remarkable since much of what Winogrand looks at involves vacancy, and much of what he expresses seems, beyond the joy and the laughter, to push up toward despair. But in the end, somehow, his work makes you feel better. It’s redemptive. Truly.

Does he tell you the world is beautiful? No. Does he tell you America is a great country? No. Does he tell you Americans are wonderful people? No. Does he tell you anybody is wonderful? No. It’s a very cold sort of redemption that he offers you. But he does promise you the idea that if you can see clearly and truthfully enough, you will have a piece of solid ground, irreducible, on which to stand. You may even become, in some way, noble.

—Leo Rubinfien, interviewed by Alexander Strecker

Garry Winogrand

Edited and curated by Leo Rubinfien

Publisher: Yale University Press

Hardcover: 448 pages