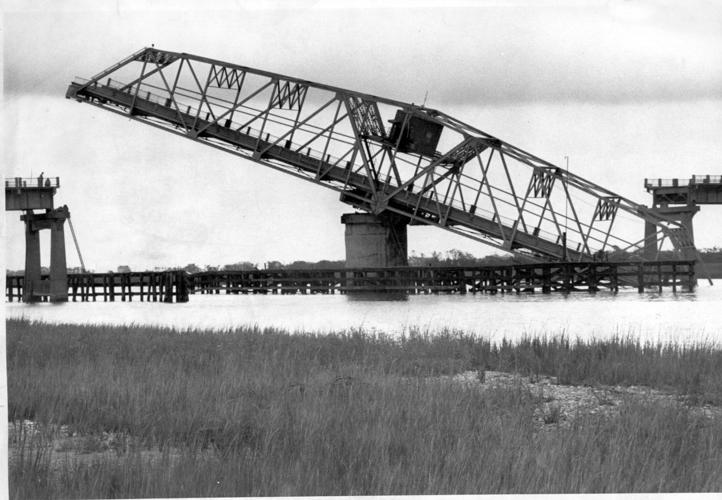

The tilted-over wreckage of the Ben Sawyer Bridge after Hurricane Hugo has become one of those iconic images of the destructive storm.

The first time structural engineer Mark Nelson saw it for real, a day after the storm, he was aboard a boat rounding under it from Charleston Harbor. His job was to put it back up straight — as soon as possible.

Retired Army Corps of Engineers structural specialist Mark Nelson. USACE/Provided

The sight "was kind of nauseating," he said.

Nelson, now 63, is a retired Army Corps of Engineers structural specialist. He had returned from evacuation after Hugo, climbed over a fallen tree to get into his Mount Pleasant home, and picked up the telephone just to make sure it was dead.

Somehow it wasn't. His boss was on the line. Get out to the bridge, he told Nelson.

The Ben Sawyer technically is S.C. Department of Transportation property. But DOT couldn't get to the repairs immediately. The Intracoastal Waterway it traversed was Army Corps responsibility.

And in 1989 the bridge was the only way back and forth to Sullivan's Island and the Isle of Palms unless you traveled by boat. The islands had been torn to shreds by the 130-mph-plus winds and storm surge. Their residents needed help.

The span of the bridge that swings open so boats could pass had been blown off its tracks on the center pin, or the middle pillar balancing the bridge. It sat like a seesaw on the edge of the pin, the lower end in the water and the other 100 feet or so in the air.

The lower end had submerged far enough that the boat Nelson rode on could be beached on its roadway like a boat ramp.

"It was very strange to pull the boat up and climb the bridge roadway to check on it," Nelson said.

But he saw something.

"The swinging span itself wasn't damaged. It was tilted off the center pin, the trusses under it were damaged. But it was still good. If you could get it back on plane, people could drive it until it was repaired," Nelson said.

If.

A ferry negotiates the Intracoastal Waterway by the Ben Sawyer Bridge in Sullivan's Island in this Sept. 28, 1989 file photo. The bridge was damaged by Hurricane Hugo. The ferry is carrying equipment from Mount Pleasant to Sullivan's Island until the bridge was repaired. File/Staff

Pacing off the length of the span a step at a time, compiling notes and guesses about the weight of components with a pencil and paper as he strode, the engineer came up with a number that staggered him. The 124-foot-long swinging span weighed 1 million pounds, about the heft of 40 school buses.

Nelson had to find a crane that could lift that and set it gently back in its tracks, working from a barge on the water or from the bed of the Intracoastal Waterway. A big crane.

He brought his sketches back to his boss, Hal Smith.

"If you drop that bridge in the waterway," Smith told him, "it's yours."

Finding a crane that big turned out to be a problem. But Hardaway Construction, a Savannah-based company that performed mostly dredging work, said they could do the job. They brought up a crane and mounting frames on two barges, all of it looking too modest to handle a 500-ton bridge span.

They were still welding the frames together as they pulled up. But the contractor had what Nelson called a brilliant idea: The crane didn't have to lift the span, the tide would.

Working at night, the crew positioned the frames. The crane cranked up belching smoke, to try to raise the sunken end of the bridge like you'd lift the end of a seesaw, to get the span even. Nelson had asked, but the contractor never told him what weight the crane was rated to lift.

"It was blowing smoke pretty hard. The bridge came up pretty easily, but I was glad to see it move," Nelson said.

Then they waited. The tide rose and the mounting frames with it, gradually lifting the bridge above the center pin. Now they had to get it positioned directly over the shoes, or pockets in the pin where it was supposed to sit.

The tugs pushing the barges danced, Nelson said. He'd never seen a tug move that nimbly. The bridge span moved closer and closer to the shoes. The tugs brought it within 12 inches, near enough that Nelson had an urge to reach out and pull it into place.

But they couldn't get the last foot. With the tide starting to drop, the tugs pulled back to wait 12 hours for it to rise again.

The following night, the tugs brought the span back over the pin. This time, the Hardaway Construction crew pulled out come-alongs, manually cranked winches. The 1-million pound Ben Sawyer Bridge was winched into place by hand.

Nelson and the contractor boss climbed into his beat-up old Ford Taurus and became the first people to ride across. Job done — maybe.

No sooner than the Taurus cleared the bridge, Nelson looked out over the water to see a tug, with a dredging barge in tow, crank up its motor to squeeze under the bridge. Its crew hurried to pull down antennas and anything else they could off the roof of the tug.

All that work, Nelson thought, and now the fixed-in-place span is going to get knocked into the water by a tugboat cabin.

The tug cleared by 6 inches, one more amazing little bit of fortune that included Nelson guessing the bridge weight within 6 percent and Army Corps cost estimator Jim Henderson nailing the $250,000 price to do it almost to the dollar, to get the funding.

Army Corps of Engineers cost estimator Jim Henderson. USACE/Provided

Henderson had figured the estimate for two cranes — to lift both ends of the bridge, he said.

Within two weeks of Hurricane Hugo, the Ben Sawyer Bridge was back in operation, even if it couldn't swing.

"It meant family and friends could go back home," Nelson said.