Isn’t She Good—For a Woman?

How the feminist passion for Artemisia Gentileschi’s life story risks overwhelming her artistic talent

Artemisia Gentileschi is a painter who makes you feel like a mind reader. Even by the high standards of 17th-century Europe, her work is impressively sensuous, dynamic, and psychologically acute. This winter, she became the first woman in the 197-year history of Britain’s National Gallery to receive a solo exhibition. The reviews have been adulatory.

The paintings on show include a significant proportion of wronged or vengeful women. There are depictions of the biblical character Susanna, caught bathing by two men, and Gentileschi’s self-portrait as Saint Catherine, posing with the wheel on which the martyr’s body was broken. In the second room hang her masterpieces: two huge canvases of Judith, another biblical heroine, sawing off the head of Holofernes, having been sent to seduce and kill him. These have echoes of Caravaggio, but an aggression that is all their own.

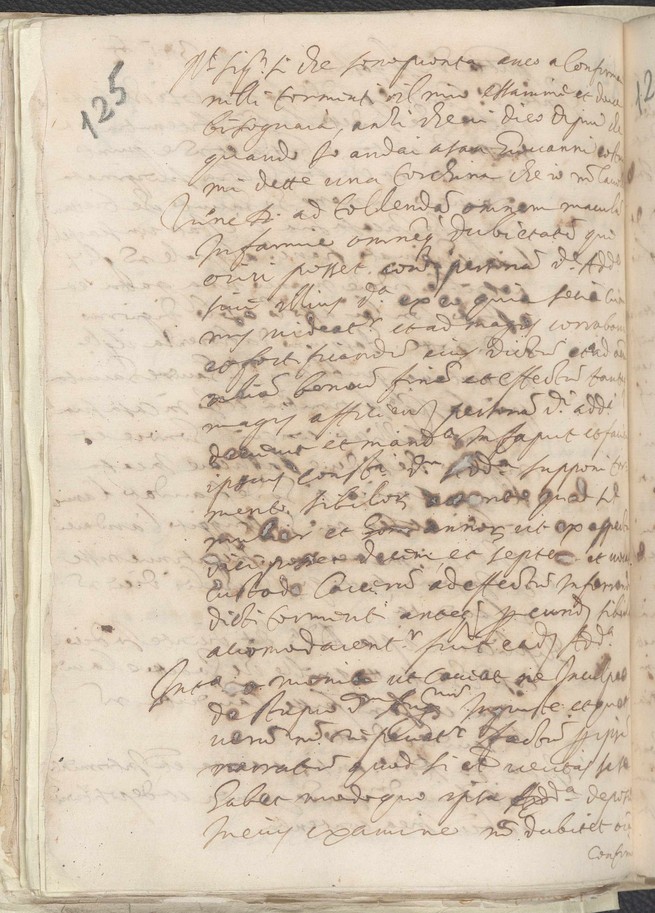

The exhibition also contains an object that makes its curator, Letizia Treves, uneasy: a heavy book, its tissue-thin pages open to a record of a court case. A teenage girl was raped by her father’s apprentice, and when her attacker would not marry her—the expected redress at the time for taking her virginity and reducing her worth on the marriage market—the victim’s father sued him. The teenager had to testify under torture, a practice designed to discourage false accusations, with loops of string wound around her fingers. These were tightened until she cried out, “E vero, e vero, e vero.” It’s true, it’s true, it’s true. Unbroken, she then looked at her rapist and, referring to the loops of string, said: “This is the ring that you give me, and these are your promises.”

That teenager was Gentileschi; the man convicted of her rape was another painter, Agostino Tassi. He could not marry her, because he already had a wife. Gentileschi, already a promising painter, had risked her future livelihood—her precious hands—by testifying against Tassi.

So why the discomfort over showing the trial record? “To a modern audience, it’s really shocking,” Treves told me. But historians have found that such trials were common in early-17th-century Rome, and Gentileschi’s experience “strongly follows a sort of formula.” (She maintained a relationship with Tassi for several months after the assault, and to the court, his offense was refusing to marry her, rather than the rape.) In other words, we should not impose modern ideas about sexual consent onto the situation in order to turn Gentileschi into a modern feminist heroine. “She was probably in love with her rapist,” Germaine Greer wrote of Gentileschi in her book on female artists, The Obstacle Race. “He was a dashing figure, handsome and black-bearded, often to be seen on horseback and sporting a golden chain.”

The story has inspired several plays, and the 1997 film Artemisia. In the Judith paintings, Holofernes is allegedly modeled after Tassi, prompting Gentileschi to be called the “#MeToo Artist.” And in Greer’s account, the rape was what allowed Gentileschi to become an artist at all. Although Tassi was convicted, he had powerful friends and never served his sentence, while Gentileschi’s reputation was no longer spotless and she was quickly married off. “The abortive trial had left Artemisia nothing but her talent. It also removed the traditional obstacles to the development of that talent,” Greer writes. “She could no longer hope to live a life of matronly seclusion: she was notorious and had no chance but to take advantage of that fact.”

Yet allowing an artist’s biography to dominate her critical reception—finding the Judith paintings more interesting as an expression of revenge than as a work of art—concerns Treves. “There is no question that her personal experiences, like any artist’s personal experience, shape the making of their art,” she said. “But I also think just to look at these paintings in that vein, it’s not particularly helpful. It diminishes her artistic achievement.”

So when does feminist celebration become patronizing, an implicit silver medal? (Isn’t she good—for a woman?) As rarities and exceptions, women are often defined by their biography. Never mind the talent—how do we feel about her? Feminist rediscovery risks saving women from obscurity only to conscript them into a reductive triumphal narrative. Gentileschi is such a striking example of this debate that we could name the dilemma after her: the Artemisia Problem. Is she good—for a woman? Or good enough to deserve a place in the canon, regardless of her sex?

The danger of “rediscovery” is an implicit demand that women must be good people, inspirations, role models, trailblazers—people worth rescuing—something that is not asked of lecherous Picasso; violent Caravaggio; or Francis Bacon, the sadomasochist. A related version of the argument insists that women who reach high office are worth celebrating only if we agree with their politics.

At its worst, well-meaning feminist rehabilitation can create a new prison to replace the old one. The quest to reverse our condescension toward muses, the novelist Zadie Smith has argued, resulted in off-putting biographies that were often “unhinged in tone, by turns furious, defensive, melancholy, and tragic.” These underdog narratives “kept the muse in her place, orbiting the great man.”

The court records in the National Gallery’s exhibition also keep Gentileschi orbiting her rapist. “In my view, and the view of most people who are writing about Artemisia today, we want to throw up our hands and say: Enough already about the rape trial; let’s talk about her as an artist,” Mary Garrard, an art historian and the author of Artemisia Gentileschi and Feminism in Early Modern Europe, told me. “It’s not the fact that she was raped; it’s what she made of the experience.”

What she made of it was art. Gentileschi is a psychological painter. Her 1610 portrait of Susanna is a study in power. The composition shows her vulnerability—two clothed men looming over a naked woman—and her face shows fear. Susanna knows that if she is attacked, her word is worthless. “For the first time in the history of art, it was sexual harassment from a woman’s point of view,” Garrard said. “It was earth-shattering in its significance.”

Like many trailblazing women, however, Gentileschi played the system in ways that later generations might find uncomfortable. The exhibition includes mythological rapes (Danaë, Lucretia), biblical voyeurism (Susanna, Bathsheba), and incest (Lot and his daughters). “They were put next to pictures of Venus, intermingled in collections,” Treves said. “There was definitely an additional appeal for a collector to have a woman paint these pictures.” Choosing biblical subjects allowed Gentileschi to repel charges of smut. Nonetheless, her Mary Magdalene in Ecstasy looks more like an encounter with a Rampant Rabbit than a profound religious experience. Gentileschi’s notoriety as a “fallen woman” might have given the pictures an added piquancy for collectors.

Historical rediscovery is one of the feminist movement’s great successes. From the 1970s onward, books such as Sheila Rowbotham’s Hidden From History, Dale Spender’s Women of Ideas (And What Men Have Done to Them), and Joanna Russ’s How to Suppress Women’s Writing argued that the traditional canon—literary, artistic, scientific—is skewed by sexism. Many brilliant women were underappreciated in their lifetime; others were discarded by posterity. The Brontës wrote under men’s names. Marie Curie was named on the Nobel Prize for Physics in 1903 only after her husband, Pierre, also her co-researcher, intervened. Orchestras refused to play the work of female composers. Over the past 50 years, there has been a concerted effort to counterbalance this tendency.

Gentileschi is an obvious beneficiary. She was popular enough to earn a good living from painting, yet she somehow faded from view after her death in the 1650s. Dozens of her paintings are lost, or are languishing in private homes or galleries, unloved and unattributed; her self-portrait as Saint Catherine only came to light in 2017. She was “essentially a rediscovery by a group of feminist art historians in the 1970s,” Treves told me. A small exhibition in Florence followed in 1981, then a joint 2003 exhibition with Gentileschi’s father, Orazio, in Rome, New York, and St. Louis. Garrard’s diligent historical work also raised her profile. When Garrard began writing, in the 1980s, the study of women artists was “a subversive underground subject,” she told me. “It was not exactly mainstream.”

The new collected works of the Guerrilla Girls, an activist group dedicated to raising the profile of women artists, illustrate the disparity. Its most famous poster shows an artistic nude with the head of a gorilla—the disguise the group’s members adopted to conceal their individual identities. Its text asks Do women have to be naked to get into the Met. Museum? In 1989, when the poster was made, less than 5 percent of the artists in the modern-art collection at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, in New York, were female, yet women made up 85 percent of the nude models. It was a world of men looking at women, preferably naked. The Guerrilla Girls hid who they were because they wanted to keep the focus on their cause, not themselves. (You can imagine the rolling referendum on whether each artist was good enough to be allowed to complain about their exclusion from galleries.) Today, the National Gallery in London still has only 21 works by women out of more than 2,300 in its permanent collection.

After Gentileschi’s trial, in 1612, she was quickly married to a clerk and packed off to Florence, where she had five children in six years. Only two were still alive when she returned to Rome in 1620. As an adult, she was a nomad, traveling between Italian cities and even visiting the English court of King Charles I. Her voice can be heard in her letters, several of which are included in the exhibition—cheeky and lusty when discussing her lover, devastated at the loss of her second son, Cristofano. Her relationship with her father is explored in the final room of the exhibit, where their paintings hang side by side.

For Greer, the tragedy of Gentileschi is that we will never know how good an artist she could have been without the constraints of her sex. We cannot even fully assess her actual brilliance when so many of her works are missing. “We shall never know how much of her potential was expended in fruitless friction, truculently defending her independence, exacting respect from patrons who condescended doubly to a woman dependent upon their support,” Greer writes. We will also never know what Gentileschi might have been without that early experience of violence and ostracism—and whether she would have been an artist without it.

It is odd to visit this exhibition after watching Michaela Coel’s I May Destroy You, a surreal, funny, brutal 12-part television series reimagining her own sexual assault. Coel’s character, Arabella, struggles with being a “rape victim”—that flattened portrait of misery, imposed by outsiders in exchange for credibility. She jokes with police officers when reporting the crime, indulges in sexual fantasies about her attacker, becomes obsessed with revenge. “We respond to trauma and triggering situations in many different ways, it’s not always a pity party,” Coel told the BBC in June. “The whole show deals with that moment where consent was stolen from you and you lost the moment where you had agency to make a decision.”

A rapist’s power is this: to define you, against your will. Tassi has linked his name with that of a superior artist forever. And while Gentileschi has been rediscovered, and given her own solo exhibition, the price is that she is not just Artemisia the Artist but Artemisia the Female Artist and Artemisia The Raped Artist. “She wouldn’t have wanted to be remembered that way,” Treves said. “In a way, you’re giving Tassi the victory.”