Friendly Beans: Ways Around the Inconveniences of Cooking and Digesting Beans

by Corby Kummer

BENS FLUMMOX cooks, even those who know them to be a nutritional godsend and stock bags of them in the pantry. There the beans stay, waiting for the intended pot of chili or soup to be made, growing ever dustier. Beans are daunting. For years I stopped reading recipes after the words “Soak beans overnight.”What starch, no matter how admirable nutritionally, is worth all that advance planning?

I recently cooked and evaluated more than twenty kinds of beans, and I found ways around the inconveniences they present of both timing and digestion—powerful disincentives for many home cooks. In my extensive sampling I came to value beans highly, not just for the rich stores of protein and iron they offer with almost no fat but also for their taste. Although a great many beans are, admittedly, insipid, some of the beans I cooked are richly flavored—mainly old kinds that fell out of use but are today available as “heirloom" beans. I now find myself craving beans, both in the southern, Mexican, and Cuban dishes for which they provide an earthy base and in the simple Italian-style salads in which the beans themselves star (a good source for recipes is the recent Verdura, by Viana La Place). Cooking beans no longer intimidates me. even if it does take time—less time, though, than you might suppose.

LIKE ALL legumes, beans are seeds that grow encased in pods. Certain varieties are bred so that the pods will be soft and tasty, and we eat them as green or snap beans while the seeds are still immature. Matters would be clearer if green beans were called “green pods.” since everyone rightly ignores the embryonic beans inside. “Shelling” beans are eaten when the seeds are mature and plump but still moist, by which time the pods are too woody to eat. The most familiar are the lima beans we usually buy frozen (garden peas are closely related to, but not members of, the main bean genera), and the best are fresh fava beans.

Favas, lentils, and chickpeas—or garbanzos, a Spanish word derived from the Greek—were among the few beans eaten in the Old World. Columbus and his fellow voyagers brought home the beans in the species Phaseolus vulgaris, to which nearly all familiar beans belong—pintos (usually too bland to bother cooking), kidneys, brown, and white, among others—and also limas, close relatives (which I find intolerably acrid when dried, and reminiscent of school cafeterias).

Fresh favas, temptingly described in Italian cookbooks and until recently restricted to home gardeners, are now grown commercially in California and are widely available in April and May. They are the same bright color as fresh lima beans, but their taste is far sweeter and fresher. Buy fresh favas early in the season (that is, now), when you need only remove them from their pods, which are furred with a downy white blanket. You can dress the beans for a salad or eat them out of hand with wedges of the sheep’s-milk cheese pecorino, as Tuscans, who are famous bean-lovers, do in the spring and early summer. (A fresh Spanish manchego, also a sheep’s-milk cheese, is just as good.) Later in the season the seed coats begin to harden, and you must remove them from each bean—tedious work, but still worth it. At that point the beans are good for purees and soups. With any kind of bean, a few months after the shelling stage the pods have dried to a crackly parchment and the beans inside are hard. These are the beans that need soaking and that wait, accusingly, in the pantry.

The primary reason to soak beans is to rehydrate them, which will tenderize the tough seed coat and thus reduce cooking time. Some kinds of beans have thin skins and need no soaking (except in order to render them more digestible, as I’ll explain). Among them are lentils, split peas, and black-eyed peas—the essential ingredient of the southern dish Hoppin’ John and a bean of Asian origin that became a staple in Africa, from where slaves brought it to America. Sally and Martin Stone, in their excellent book The Brilliant Bean, say that beans need soak only four hours, with the exception of dried fava beans (which, even when soaked overnight, cook to an acid-tasting mush—no wonder the Italians prefer them fresh) and soybeans, which few people cook. By then the beans will have doubled in size and the skins will have puckered.

Dried beans should be from a recent harvest. If they’ve been sitting on the shelf for more than a year, they will have lost flavor and might be tough, no matter how long you soak and cook them. Unfortunately, it’s difficult to tell by looking at beans if they’re too old. The best strategy is to buy from a market where turnover is high.

Soak beans in plentiful cold water— at least three times as much by volume as you have beans. Never salt soaking or cooking water, because salt will toughen the skin and prevent the beans from softening; so will any acidic ingredient, such as tomatoes or lemon juice, which should be added only after the beans are cooked as soft as you want them (it helps to know this if you want beans to keep their shape during further cooking in a stew or soup). Some cooks add baking soda to the cooking water, as a tenderizer, but this damages cell walls and allows nutrients to leach out.

The Stones offer two methods of quick soaking, for when you don’t have time to let beans soak four hours or more. Put the beans in a large saucepan and add enough water to cover them by two inches; boil for two minutes; remove from heat and soak for one hour; then drain, rinse, and cook. Or boil the beans for ten minutes, drain, cover them with two inches of cool water to soak for thirty minutes; drain, rinse, and cook.

The rest is easy. Bring a fresh pot of water to the boil, add the soaked beans, keep the pot covered, or partly covered, on a very low simmer, and start checking the beans after an hour. Add hot water if necessary to keep the level two inches above the beans. If you cover beans with too much water, according to Philip Teverow, who has helped popularize many kinds of heirloom beans by stocking them at the New York store Dean & DeLuca, they will take longer to cook. Most beans wash out to a paler color with cooking, and they often lose their gloss. I found that most kinds took about an hour and fifteen minutes to become soft. You can test for doneness by rinsing a bean in cool water and pressing it against your upper palate, or by mashing one on a counter with the back of a spoon. Beans should not be al dente. They taste better and are easier to digest when fully cooked.

One of the purposes of maintaining a low simmer is to keep the beans from splitting, but some varieties will naturally break open during cooking, and all you can do is use them in soup or a puree. These include, in my experience, French Horticulture, a very good bean from Phipps Ranch, a farm near San Francisco that grows many heirloom beans, and Appaloosa, a marvelous-looking small white bean with maroon splotches. The custardy interior of French Horticulture makes an especially nice puree. Both Phipps Ranch (415-879-0787) and Dean & DeLuca (800-221-7714) sell Appaloosa and many other heirloom beans.

If you want to use beans in a salad or another dish in which appearance counts, lift them out of the cooking water with a slotted spoon and rinse them. Dumping them into a colander crushes the ones on the bottom. Varieties that can be relied on to stay intact include pinto beans and their many better-flavored relatives, and cranberry beans. which are the same size as pinto beans but colored as their name suggests and superior in flavor; cranberry beans are the ones to use in the many Italian recipes that call for borlotti.

Some beans require no forethought. Lentils and split peas, soaked or unsoaked, take as little time to cook as rice. After ten minutes (for red lentils) to a half hour or so (for most other lentils and split peas) they can mercilessly turn to mush, so watch very closely if you want to eat them whole. Look for lentilles de Puy, olive-drab lentils grown in volcanic soil in France, which taste better than any other; Dean & DeLuca carries them. Blackeyed peas and their relatives pigeon peas require thirty minutes to an hour. Flageolets, small celadon-colored beans that look like Chiclets, can also be cooked without soaking and must also be watched lest they disintegrate. The French serve flageolets with lamb, but they are good with any meat or fish. My favorite bean, they have an elusive, subtly sweet flavor reminiscent of fresh peas.

You can cook beans in a microwave oven or a pressure cooker. The time saved with a microwave can be as much as half (although this does not make them instant), and beans seem to keep their shape reliably, according to Barbara Kafka, who provides cooking times in Microwave Gourmet. Pressure cookers make very quick work of even unsoaked beans, but they spell trouble to many people, especially those whose childhood memories include pea soup on the ceiling (hearing the loud pffsss, my mother would announce, “It’s going to explode,” and wait it out on the back porch). Today pressure cookers have far superior safety valves, and two precautions almost guarantee placid cooking: keeping the cooker no more than half full of liquid, and adding a tablespoon of oil, to prevent loose skins from floating free and clogging the valve. Most soaked beans require twelve minutes or less, according to Lorna Sass’s Cooking Under Pressure. Unsoaked beans take longer, but generally less than a half hour.

When you bother to cook beans, you should cook a lot, because they can be frozen so successfully—they will keep their flavor and nutrients for at least six months. If you freeze them in small portions (Zip-loc plastic freezer bags are the easiest) you can add a cup or so to a soup or stew at will. A light tossing with oil before freezing will help keep the beans separate and tender.

Infants and children, too, can enjoy and digest beans. Friends on the lookout for sources of iron to feed their children report that their infants find pureed lentils more appetizing than whole-grain cereals. Carlene Hamilton, a nutritionist at the University of Kentucky, says that lentils, mashed split peas, or mashed limas (but not other beans) are a fine component of the diet of a child under two, although they should not be the basis of one; you can add any beans to the diet of older children as you would to your own.

WHY BEANS cause gas is fairly straightforward, yet even people who devote a great deal of time to researching how beans are metabolized seem a bit self-conscious discussing it. (Scientists I talked to often began by reciting the rhyme beginning “Beans, beans, the musical fruit” or by chuckling over the memory of the campfire scene in Blazing Saddles.) As beans dry, they store complex sugars called oligosaccharides. Normal digestive enzymes are unable to break down these chains of sugars, so they pass whole into the lower intestine, where friendly bacteria to which we play host eat the sugars and ferment them. This process is similar to the fermenting of other sugars, and a natural by-product is gas. (Fermented black beans, popular in China, and the soybean foods tofu and tempeh all lose oligosaccharides in processing and are thus more easily digested.) The gases produced in the lower intestine, including methane and hydrogen, are odorless. Beans “burn pretty clean,” in the words of David Jenkins, a professor of medicine and nutritional sciences at the University of Toronto. It is the condiments you eat with beans that are likely to cause detectable problems. Onions, leeks, and to a lesser extent garlic contain not only oligosaccharides of their own but sulfur compounds besides, which cause odors. So if you eat onions and garlic with beans you’re likely to add embarrassment to discomfort.

Luckily, a large percentage of oligosaccharides are water-soluble, so you can soak them away. It’s more practical to concentrate on soaking them out of beans than out of onions or garlic, since you have to soak beans anyway. During soaking change the water once or twice, rinsing the beans before you add fresh water. Even if you simply drain and rinse the beans once before cooking them, you’ll still get rid of some oligosaccharides.

To go the extra mile, take one more step after you have followed whichever soaking method you choose. Bring the beans to a boil, covered by two inches of water, boil them for five minutes, drain and rinse them, cover them again with two inches of water—preferably water you have boiled separately, so that you don’t slow the whole procedure—and continue cooking them. This step is an especially good idea if you used a quick-soak method or had no time to change the soaking water.

If we just ate beans all the time, it seems, this Lady Macbeth-like rinsing would be unnecessary. In studies he has conducted, David Jenkins has found that over time people develop the capacity to digest beans efficiently. The trouble, he says, is that it takes not a week or two but several months to adapt. And the colon will retain its new ability only if you keep eating beans regularly.

Help might come in the form of a bean bred to be gasless. James W. Anderson, a professor of medicine and clinical nutrition at the University of Kentucky, says that a “user-friendly” bean low in oligosaccharides is being studied in England. The goal of scientific research on beans is not so much to make them more digestible as to study their healthful properties: beans stabilize blood glucose, which makes them good for diabetics, and they apparently lower blood-cholesterol levels; their high fiber content seems to play a part in the comparative freedom from colon, breast, and other cancers which is enjoyed by populations whose diet is based on beans. Anderson is also looking into the ability of beans to lower blood pressure. “We think beans have been neglected,” he says.

Help has already come in the form of Beano, the trade name of a digestive enzyme that is said to break up oligosaccharides before their descent into the lower intestine. You squeeze eight or so drops of the salty liquid on the first bite of beans, and have few problems digesting them, according to Alan Kligerman, the inventor of Beano and the owner of the company that makes both it and Lactaid, the trade name of an enzyme that can help lactose-intolerant people digest milk products. (You can call 800-257-8650 to find out where Beano is sold near you.) Kligerman says that unpublished studies support the effectiveness of Beano, and promises that once they have been peer-reviewed, the studies will appear in clinical journals.

Beano is especially helpful with beans that have not undergone elaborate soaking and rinsing, which is to say most canned beans and beans you eat in restaurants. Canned is the only form in which many harried home cooks ever use beans, and in the case of chickpeas, which take forever to cook, they are almost a necessary shortcut. There’s nothing wrong with canned beans except that they are salty and their oligosaccharide content may be nearly as high as it was when the beans were raw. Drain and rinse them before adding them to a dish.

MOST COOKS are more interested in adding flavor to beans than in taking away oligosaccharides. Theo Schoenegger, the chef at San Domenico, in New York, serves a dish of cannellini (white beans) and fresh Alaskan shrimp in a sauce of pureed white beans thinned with stock and seasoned with rosemary-infused olive oil. (Good cannellini, like those from Phipps Ranch, practically demand olive oil.) The dish shows how good beans can be, at once rustic and elegant. Paula Wolfert, whose most recent book is Paula Wolfert’s World of Food, once told me that she knew after a single course that Andrea Hellrigl, the chef at Palio, in New York, was a master, because he knew how to cook flavor into his beans. In her classic Cooking of South-West France, Wolfert gives a recipe for red beans or red kidney beans that shows how any ambitious cook can do that: the beans are cooked with an onion stuck with two cloves, a cinnamon stick, a chopped carrot and onion, a pig’s foot, goose fat, pork butt, garlic, parsley, bay leaf, and thyme, among other things.

You don’t have to search out a special butcher to give beans flavor. Add to the cooking water celery, carrots, and onions, either raw in chunks or first sautéed slowly in olive oil for twenty or thirty minutes, and all kinds of fresh herbs, particularly rosemary, sage, and bay leaf. Some form of ham hock or pork butt or, best of all, a prosciutto or ham bone will add wonderful flavor and slowly render fat, tenderizing the beans. Olive oil in the water will also do this.

Beans reach their apotheosis in pasta e fagioli, perhaps the strongest contender to be the national dish of Italy. I have happily eaten this thick soup— part puree, part whole beans, with pasta cooked right in the soup—both when I was famished and when I thought I could never eat again. It is wake-the-dead food. Every region of Italy has its own jealously guarded version—in fact, every town does, according to Fagiolo Mio, a charming Italian book by Savina Roggero and Mariarosa Schiaffino. Many Americans have encountered it as pasta fazool; fasul’, a Neapolitan dialect word for “bean,” is close to the Greek root phaselos (the Greeks ruled and named Naples). Fagiolo Mio declares the Veneto to be the true home of the soup, although Tuscans would vigorously disagree. Any grain acts as a complementary protein with beans—Italians in other regions put rice, barley, or polenta in pasta efagioli, for instance—as do bits of ham, sausage, or cheese.

Since arguments over the absolutely right version of pasta e fagio li are endless, I give a recipe adapted from the wise writer and historian Anna Del Conte, who presents a Venetian one in her Gastronomy of Italy. For four people (you can easily double or even triple the recipe) soak a cup of cranberry, pinto, or, if you can find them, Jacob’s Cattle beans (both Dean & DeLuca and Phipps Ranch sell these) in the way that is most convenient for you; drain and rinse them. Heat two or three tablespoons of olive oil in the bottom of a stockpot and sauté two ounces of pancetta (unsmoked bacon), if you can find it, or prosciutto or bacon—the bacon preferably boiled briefly to desalinate it. (You can omit meat, of course.) Add an onion, a clove of garlic, a carrot, a stalk of celery, and several needles of rosemary, all chopped, and saute slowly for at least fifteen minutes, until the vegetables are soft. Add the beans and a ham bone—Del Conte calls for an unsmoked ham hock, but add what you can find, if you are using meat—and cover with seven and a half cups of meat stock (you can use chicken or vegetable stock). Simmer slowly, covered, for ninety minutes or so, until the beans are tender. Remove the ham bone and puree half the beans in a food mill or a food processor. Return the puree to the pan and raise the heat to medium high. When the soup comes to a boil, add six ounces of dried tagliatelle or wholewheat spaghetti (or whatever dried pasta comes to hand), salt, and pepper. If the soup seems dense, add hot water before you put in the pasta.

Serve when the pasta is done to your liking, passing around a bowl of freshly grated Parmigiano-Reggiano cheese. Traditionally, bean soups that have been made with meat fat are enriched with cheese bur no oil; those with a base of olive oil receive a final drizzling of aromatic olive oil. This soup is of course open to many variations, particularly in the amount and number of fresh herbs you add, and once the beans are soft you can add a few tomatoes, too, which often appear in other versions. The soup gets better after a few days.

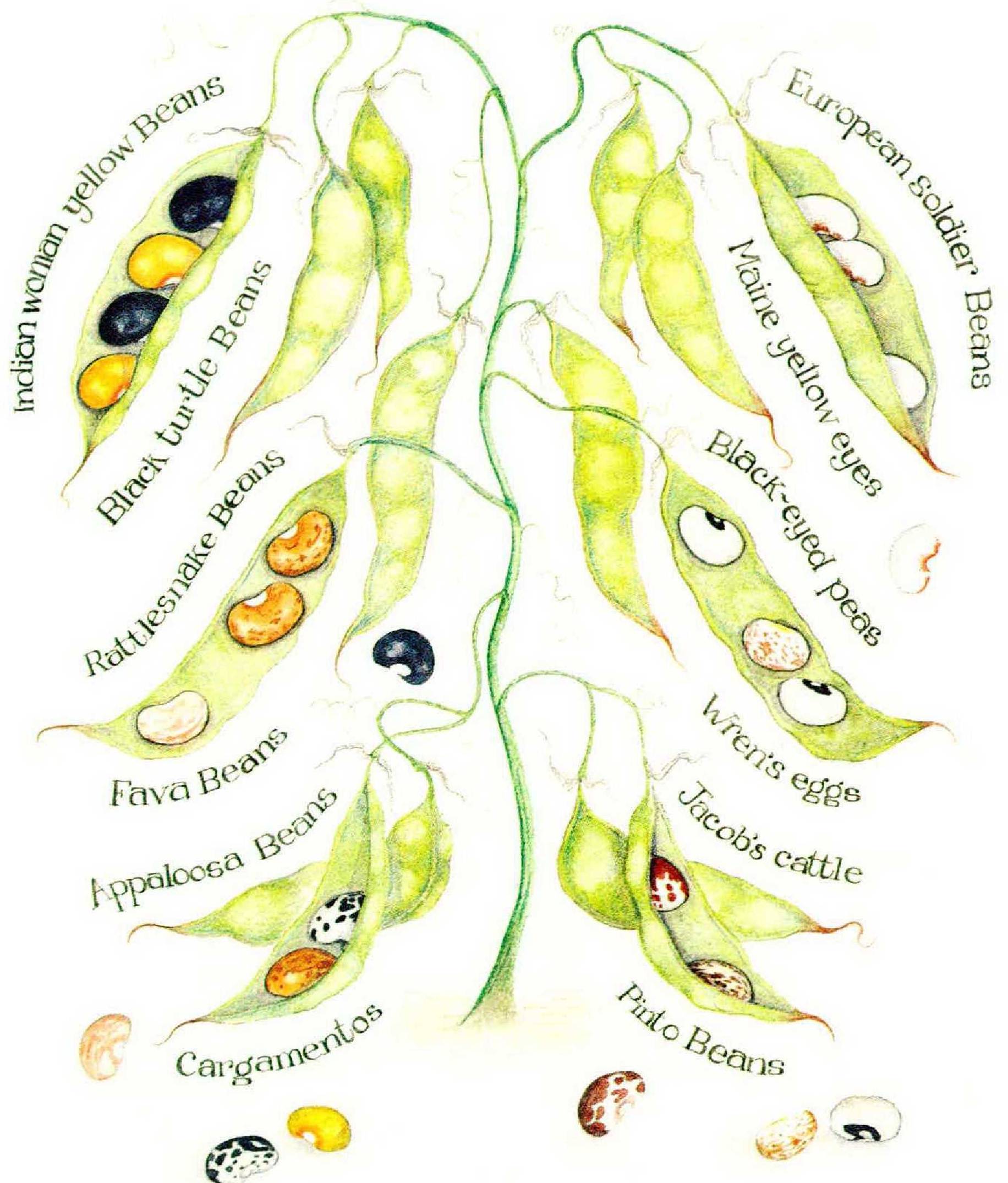

B EANS SOLD by Phipps Ranch and Dean & DeLuca are usually from the current year’s crop, and for that reason alone it’s worth ordering beans from them. Both sell popular beans like pintos and black beans, and heirloom beans as handsome and perfect as polished stones, most of which have evocative names (Maine Yellow Eye, Indian Woman Yellow, European Soldier). Others worth ordering for their taste and firm texture are Rattlesnake (from Dean & DeLuca), the plump Wren’s Egg (from Phipps), and Jacob’s Cattle. Phipps is growing a beautiful big white bean called Pueblo, whose meaty flavor and creamy texture make it a standout; unfortunately the company won’t have enough to sell until next year.

Or you might think of growing some beans of your own. Alan Kapuler, who raises organic plant and vegetable seeds in Corvallis, Oregon, offers many kinds of heirloom beans. (He describes 992 kinds of seeds and plants in this year’s catalogue, which you can get by sending $4.00 to 2385 Southeast Thompson Street, Corvallis, Oregon 97333; a seed list is free.) Kapuler recommends Oregon Giant as a bean that will be good in all its stages: as a green bean with a succulent pod, long and thick; as a shelling bean; and as a dried bean. He and other seed growers offer beans to suit every palate—and every eye.