David Hockney: A Bigger Picture is radiantly bright, spectacularly large in both scale and extent and ebullient to the point of jubilation. It is also garrulous, gaudy and repetitive. Yorkshire may have called Hockney home from the Hollywood hills to paint the landscapes of his boyhood with a zest nearly unparalleled among septuagenarian masters, but the results are bafflingly low on singularity, emotion or depth. They lend themselves dismayingly well to Royal Academy merchandise.

If only it wasn't so. Hockney is justly admired, not to say adored, for his pictorial ingenuity, his superlative draughtsmanship, his deft and witty inventions. Which other living artist has created a modern masterpiece to compare with A Bigger Splash, that stunning diagram of Californian heat and cool water, of liquid blossoming into frozen chaos? Which other living artist has entered the public imagination so completely?

His lifelong campaign for painting, his pushing of figuration as an evergreen genre, his willingness to enter into public argument, his constant self-renewal as an artist: Hockney is a most appealing figure. And here he is making another appeal, this time for the old tradition of landscape.

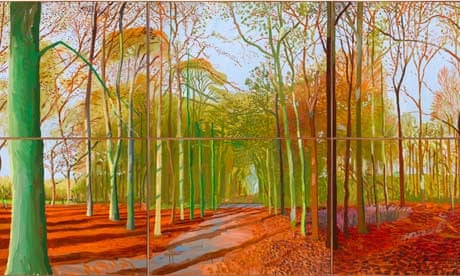

It is a huge risk, undertaken on a gargantuan scale. The latest works here were made in the last eight years in the East Yorkshire Wolds near Hockney's Bridlington home. Some are a mere metre or two square, others as big as billboards, and the largest is more than 15 metres across. For comparison, think of Monet's giant water lily panoramas and then imagine something more than twice the size. I've never seen a bigger painting.

So that is an advance on the past of a sort. And for such a restless innovator, so mindful of art history in everything he makes, this is surely a necessity. To take up a genre beloved of old and modern masters, Sunday painters and about half the entrants to the Royal Academy show every summer is to join a tradition. The question is what to make of it in personal and aesthetic terms, how to renew it.

This is, oddly, what Hockney ducks in his recent body of work. The compositions are exactly average: down the lane, up the hill, into the woods; rosebay willowherb dotting the hedgerows, bales like big cotton reels, gleaming puddles at sunset. Bigger, brighter, more or less graphic, naturalistic or chromatically loud, they have nothing special to declare about that point where the road disappears beneath an arch of boughs, for instance, other than its happy familiarity – over and over.

The show does open magnificently with The Four Seasons in the Royal Academy rotunda, a terrific, all-year-round series from saplings and early green grass to high summer's glowing harvests and winter trees against a dying opalescent sky. These recent paintings are voluptuous, appreciative, joyous, finding new notations for every change in this small corner of England.

The brushwork is lithe, running riffs on past art from Seurat's screens of pointillist dots to Matisse's buoyant stripes. The majestic scale accords with the ancient cycle of death and rebirth. The colour appears meaningful – gold against marigold, wintry blues, ochre and magenta producing optical flares – and has not yet become a sore point.

But A Bigger Picture wants to present Hockney as a lifelong landscape artist. In no time we are back to the 90s and The Road to York Through Sledmore, dipping up and down between blazing orange buildings and eye-popping foliage. Veridian and violet emerge straight from the tube, red brick is virtually scarlet.

In Saltaire, the picture turns childlike: here comes the chuffing train, here's the street snuggling over the bridge and those neat little back-to-back boxes. In the Wolds, the patchworks of fields are precisely that: striped squares of turquoise and lemon, Indian pink and gold; Matisse crossed with Walt Disney. Sometimes this comes out beautifully, as in Garrowby Hill, where the road is fairly bouncing down the hill, taking the curves very steeply, then narrowing to a distant ribbon. The colour is wild, but everything from the geometry to the perspective feels classically precise. The contrast is exuberantly comic.

But that's it for the humour. This is the first Hockney show I have seen that appeared completely in earnest. There is no display of pictorial wit, other than in the room of 60s landscapes that includes the wonderful Journey to Switzerland, with its figures haring along in the motorcar as the mountains behind them transform into flag-edged maps. Hockney is for the most part outdoors, painting straight from nature.

And he cannot stop, cannot keep still. There is not just Yorkshire to get down, but the seasons as well. A wall of sweet midsummers followed by a wall of yellow harvests followed by felled logs in autumn and bare glades in winter. A nice spot of painting in the sun (it never rains) and then home to tea; it sometimes feels as complacent as it looks.

Yet what is at stake is always making and medium, not the plein-air experience itself. Hockney doesn't have his nose deep in the hedgerows or his eye on the ephemeral dewdrop. He is not primarily interested in the ever-changing rhetoric of weather, light or nature. He is thinking about picture-making and so, perforce, is the viewer.

How they are made – this kind of mark, that variation on Van Gogh, those Fauve-bright colours or stylised cut-outs or vast, multi-panel grids – these are the constant focus, much more than the landscape itself. Every work compares with another and each has its alibi in the whole. It is one enormous study in comparative methods.

So it feels pointless, after a while, to look for an ominous pressure of heat or even a particular kind of tree. There is no underlying metaphor or building emotion, no sense of awe or melancholy or even much amazement. It is all things bright and beautiful all the time, with the possible exception of solitary stumps in winter clearings.

Though even here, among the skeletons of dead trees, the high-pitched purple and orange gives a kind of luminosity that just clears those blues away.

Hockney's colour is matched to his energy. People coming out of the Royal Academy speak fondly of all this dynamic heat in January. But against this chromatic freedom – lime green, acid pink – is a neutralising tidiness. It isn't just those regular blocks into which the big works are split for ease of construction; it isn't even the superlatively concise draughtsmanship that underpins every image. It is a kind of graphic fastidiousness – nothing too out of place or too wild – bordering on neatness. Can Yorkshire be like that these days?

The gallery full of hawthorn blossom is an exception. Look at these images in reproduction, on a tiny scale in the comfort of your own home, and they may well appear absurd, the white hawthorn bursting out in great maggoty slugs, the shadows making glove puppet bunnies. But in the gallery, and almost lifesize, they are marvellous transformations: the alien blossom rampant in its outburst, the shadows on the hot lane bristling like cacti in the desert. They are like late Philip Guston in their coining of strange new forms and sheer force of personality.

The further Hockney gets from the middle of the road the better, but alas his latest works are made right there on the spot with an iPad. With their felt pen squiggles and eerily empty transitions, so reminiscent of Photoshop, they appear inert and dehumanised. The surface of these prints has an easy-clean sheen and at more than a metre high they look like what they are: quick studies of dandelions and leafy lanes voluminously enlarged.

Perhaps the technology has bewitched him with its efficacy and speed; and who would begrudge Hockney this pleasure after a lifetime's experiments with Polaroid, fax, photocollage, video and all. But perhaps this goes to the central disappointment of A Bigger Picture. One witnesses Hockney's excitement, verve and energy, wall to wall, floor to ceiling and in room after room without ever feeling it oneself.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion