The colours are often dull, cheap as schoolroom paints from yesteryear, greyed, yoghurty, intractable and flat. Drawing is frequently laboured and cramped, and you can imagine a man bent over the paper with a pencil or a pair of scissors, his tongue poking from the corner of his mouth and brow furrowed as he concentrates.

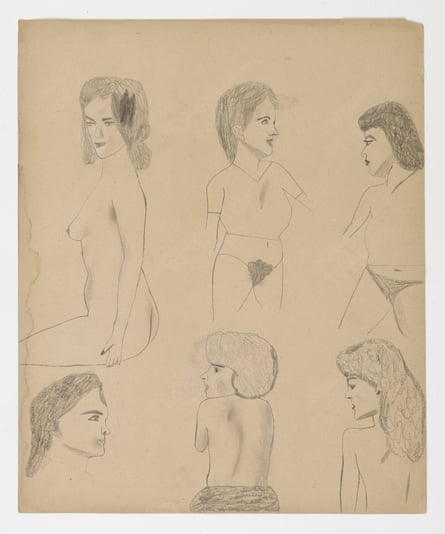

Jockum Nordström’s art looks as if it comes from another time, another place. But where and when exactly? Working on paper, and using collage, watercolour, crayons and pencil, his art has an old-fashioned air. His figures don’t only wear clothes from another age – frock coats, hats and canes, full skirts – but the way they are drawn seems outmoded, too. They might belong anywhere from the 18th century to the 1950s. Faces are characterful, but also wonky and wrong, as if their draughtsman had had no tutelage whatsoever. The artist is a stranger to anatomy, if not to body parts – breasts and noses and bums and cocks. His sexual preoccupations appear to belong to an antediluvian, pre-internet age of almost innocent prurience.

All this sounds like withering condemnation. But look again. There is something very knowing about all this, even though Nordström’s work often makes us imagine that it has been piled up under a loner’s bed, the product of an obsessive and perhaps even disturbed outsider. Nordström is in his 50s, married to the terrific Swedish painter Karin Mamma Andersson. Nordström knows exactly what he is doing. He has been doing it for years.

People in rooms, getting up to domestic shenanigans. An empty chair, bottles on the table, a phone off the hook. Someone at the door while a couple have sex on the other side. Women on their knees, men standing behind them, plumbing away. A man pontificates and points with a pipe. A couple stand before him, as if they were ashamed. Elsewhere in the house, the fucking and sucking goes on unabated.

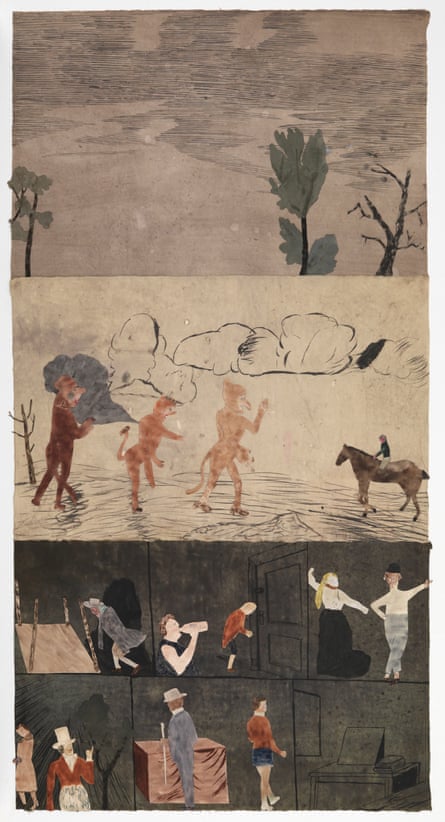

Nordström made all this work in Gotland, a Swedish island in the Baltic, almost half way to Latvia, where he sequestered himself away from his Stockholm studio for months, working alone. I haven’t the faintest idea what story he is telling. There are too many unanswered questions. A man – blue jacket, white trousers – loses his top hat as he chases a hare. There’s a dog at the door. A distraught woman points at a grave. I think it’s a woman, unless it is a man in a smock. Three people in animal costumes, who might be devils, wander the countryside, and come across a jockey on a horse, who just stands there, waiting. One of the carnivalesque ne’er-do-wells is missing half a leg. He could have been a terrible accident. Maybe the artist just gave up or forgot to draw it, which in its own way is just as bad. The sky above is grim.

The countryside always looks loathsome, in an undescribed kind of way. Stuff happens: here’s a naked woman in the sun in a blaze of light. A man on the ground and someone holding a paper and, over there, a row of houses plonked down on the emptiness. The trees are unpleasant.

Nordström’s drawings are full of compartments, like storyboards, but there is no right order. You move backwards and forwards and up and down, in the same way that you might wander someone’s house, trying doors, looking through keyholes, searching for the filth in other people’s lives, standing at the window and watching the world outside. All of which makes it sound as if the spectator is turned into some sort of creepy voyeur, but Nordström makes us less an audience and more like detectives hunting for clues at the scenes of a crime. It might be worth recalling that Ingmar Bergman lived on a small island off Gotland.

You could also look at Nordström’s works as if they were homemade illustrated newspaper pages of village life – the things everyone knows about and the things no one sees, today’s news jumbled up with a confusion of childhood memories, dreams, anecdotes and folk tales. They are much more powerful than the winsome perversities of Winnipeg artist Marcel Dzama, who also shows with Zwirner. Nordström’s work has real bite. Its sophistication takes a while to dawn.

A man meets himself on the stairs. Both look utterly unsurprised, as though their encounter were a daily occurrence. One passes the other as if they were two blokes simply accustomed to bumping into one another. This is mildly unsettling. Nordström’s titles have a similar uncanniness. One is a little poem:

I was laying down and I was sitting up

I dreamed that night

I dreamed that the song was backwards.

And what of the two women in a passage between rooms? The setting is conventional. One woman stands at the door, the other, a buxom figure who might be a nurse, bustles away. The women ignore one another. What’s that on the floor? What’s been going on in the room beyond? The wretched way the scene is drawn gives the whole thing an air not just of mystery, but misery.

And then there are the sculptures made from matchboxes and bits of card. Some are like little cabinets of secrets, or imaginary rooms, cells or perhaps even coffins. They sit on a little shelf. One looks like an abstract painting, and reminds me of a Josef Albers Homage to the Square. They all have the feel of artworks rediscovered after years at the back of a cupboard.

It strikes me that the artist who made these things is a kind of fictional creation, too: it is as if he were himself one of the characters in the drawings. There is a certain sense of hauntedness and time-slip about everything Nordström does. Days later, the feeling remains.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion