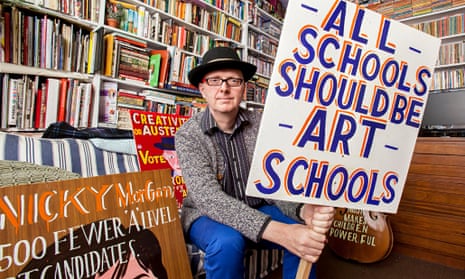

Patrick Brill, better known as Bob and Roberta Smith, is a contemporary artist whose “slogan” paintings blend the creative and the political. In 2005 he curated the successful Art U Need project, which brought captivating pieces to the streets of Essex, before co-founding The Art Party, a vehicle for promoting art in school and public life.

You have curated an exhibition, Art for All, at Yorkshire Sculpture Park, for which you delved into the National Arts Education Archive. Did you uncover any surprises?

Well, it [the archive] starts with Sir Joshua Reynolds, who set up the Royal Academy, an enlightenment project that was the first formalised art school in Britain. It was only after the second world war, though, that art education got going. You suddenly have really progressive projects like the Child Art Movement which had a vision of children’s self-expression as a kind of answer to the destruction of the war. Then, in the 1960s, there’s a rethinking of art education with artists like Victor Pasmore being involved in the creation of the first foundation course. That’s really where the modernisation of art education begins and art finally gains a standing with other subjects. It’s a journey worth retracing, particularly with what is happening right now.

Your message is that art education is now threatened, not just by government cuts but by an unspoken ideology that suggests art is not really important to a nation’s economic and social wellbeing?

Yes, and, this is not a new way of thinking. It started in the 80s with Kenneth Baker [education secretary under Margaret Thatcher, 1986-1989], who didn’t want art in his national curriculum but was persuaded that it could be graded accurately not as a voice for self-expression but as a set of skills. I want us to re-engage with that postwar consensus that we need to expand creativity and who gets involved in it. The Tories think that silly notion is history now. Politicians don’t seem to even understand the basic importance of something like design and how it underpins production. It’s crazy, and, to be honest, Labour is not much better. That Tristram Hunt is pretty awful.

Is this a particularly English way of thinking about art?

I guess so. The deep philistinism and scepticism towards art that I am talking about does seem peculiarly English, and it has come back with a vengeance under the Tories. In my book, the arts are not just important in themselves but fundamental to democracy. Kids need to think about ideas. If you teach them self-expression, you are adding to democracy. Why do you think oppressive regimes always try to censor art and lock up artists?

You stood against Michael Gove in the last general election. Only 273 people voted for you. Was it worth it?

Yes. I stood against Gove, not because I wanted to demonise him but because I wanted a public conversation with him about the importance of art education. So, in terms of highlighting my cause, it was pretty successful.

You met him on the hustings. Was there any spark of chemistry between you?

I hate to say this but I rather liked him as a person. As a character, there is something sympathetic about him. He’s pretty human compared to the likes of Osborne. I do think Michael Gove is also stuck with a demeanour which is quite quirky and peculiar. He’s a bit Kenneth Williams, who was funny and eccentric but also very rightwing. On election night everyone was crowing at the Tory victory but I sensed that he seemed rather alone somehow. He may have ruined art education but, as a person, he is not a hateful figure.

Has your election experience made you think differently about how you make art?

Yes. I think of artworks as campaigns, now [laughs]. I’d like to start a campaign to emphasise how important art is, individually and collectively, to the fabric of our lives. Free access to museums and art galleries is important but not the only measure of how we understand and engage with art. People are immersed in the arts whether they understand it or not. You can’t live in a house without encountering some notion of architecture.

Your parents were both painters and your father, Frederick Brill, became head of Chelsea School of Art. How much of your commitment to art and art education comes from them?

Well, my dad went with Henry Moore to lobby Margaret Thatcher when she was education minister in the 70s. It’s a cliche but I wouldn’t be where I am as an artist if he and my mother had not gone on their journeys into art. That generation belonged to a more democratic time when, if you were good, you were offered the opportunity of an extended education. My parents took that opportunity and thrived on it. Now we are fast approaching a time when there will not be any kids with estuary accents in art schools. It’s bad for art and it’s bad for democracy.

You are referred to in the press as a “slogan artist” or a “political artist”. Do you find those terms reductive?

I don’t mind them, not least because so few contemporary artists engage with politics on any level. I don’t regard myself as a political activist because I’m not as committed as true activists tend to be. I’m just angry about the constant assault on the arts and the destruction of education. I can be a bore on this issue but think its so incredibly important. You can’t stand back as an artist and not engage with it.

Why do you think so many contemporary artists do exactly that?

That’s an interesting question. You have the likes of Mark Wallinger and Jeremy Deller, who are politically engaged, and Anish Kapoor cancelled a show in China when Ai Weiwei was locked up, so there is a desire by some artists to address political issues. But the rise of the art market and the commercial art world in the past few decades seemed to erode political engagement – oligarchs don’t want to buy art that says that they are crap [laughs]. The YBAs bought into all that. That lot shifted the democracy of who was making art by embracing wholeheartedly the commerciality of the market. I think we are all a bit sickened by that now.

You come across as quite a colourful, almost eccentric, character. How much does humour play a part in what you do?

Colour and humour go together for me and both are immensely important. They make the work more human and fallible, though some would argue that the humour takes the edge off the work and the political engagement. But I’m not interested in making big, cast-iron statements. For me, it’s all a big, continuous conversation, so you have to have humour in there. Like life, really.

You used to collaborate with your sister, Roberta, hence your pseudonym. Did she really once say of your art: “All you do is paint the first thing that comes into your head on bits of old floorboard, and you can’t even spell”?

Alas, yes [laughs]. She defined absolutely what I do in that statement. That said, I think she is sneakily quite supportive of what I do, especially the political stuff. Proud would be going too far, but supportive, yes.

Art for All is at Yorkshire Sculpture Park, Wakefield until 3 January 2016

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion