Seven years ago, Marlene Dumas briefly became the world’s most expensive living female artist, a dizzying upward move that was reported, somewhat breathlessly, in newspapers from New York to Tokyo (her 1995 painting The Visitor was sold by Sotheby’s for £3.1m; previously, her prices had stood at around the £50,000 mark). Yet her name remains, here and elsewhere, relatively unknown. She is, you might say, the world’s most un-famous famous artist, beloved of curators and collectors, but lacking any of the tinny razzmatazz – the self-publicity, the production lines – we’ve grown accustomed to when it comes to 21st-century art. Thanks to this, the huge retrospective of her work at London’s Tate Modern next month – it will include more than 100 of her provocative and intensely dark paintings, drawings and collages – is, at this point, a hot ticket only for those in the know.

As I walk to her studio – she works on the ground floor of a tall, gabled house in an area of Amsterdam popular with both hipsters and immigrants from north Africa – I wonder about this. At first sight, it’s confounding. Dumas’s work is every bit as outrageous as that of, say, Tracey Emin, and about 50 times more interesting (unlike Emin, she looks outwards, her interest in the human body extending beyond her own to those of other people). But then I meet her, and it’s suddenly less of a mystery. Two things about her are immediately apparent. The first is her prodigious energy, which comes at you like a gale force wind. She is, quite simply, unstoppable: garrulous, clever, curious, enthusiastic. The second – this is the important part – is her modesty, her uncertainty, her artistic humility. She takes her work very seriously indeed, but herself not at all, and the jokes and self- deprecation come thick and fast. “When I start work on a painting, it’s total kitsch!” she wails at one point. “When I painted myself pregnant, I couldn’t do the legs, and the blond hair made it look like a bad Klimt!” she cries at another. No other artist I have interviewed has ever come close to making statements like these. Their acceptance of their own brilliance was simply part of the deal.

The office space in which we sit is airy, modern, very Dutch. Dumas’s assistant, Rudolf Evenhuis, makes us tea – I turn down the first offer of a proper drink; it’s only four o’clock, after all – and then swiftly disappears, having reminded her that she has another appointment in two hours’ time. She rolls her eyes at this – not at his bossiness, but at her schedule, which has been unrelenting since she began work on the retrospective (it is currently showing at the Stedelijk museum, where I saw it earlier, surrounded mostly by whispering, middle-aged Dutch women in elegant, minimalist outfits who seemed unable to get enough of Dumas’s bottoms, breasts and, well, everything else).

“It has been exhausting,” she says, of the process of putting the show together. “I wasn’t looking forward to seeing all the works again.” She collapses, as she’s apt to do, into wheezy laughter. “But then, if I hadn’t done it now, maybe I’ll be dead!” (Her English is brilliant, but sort of scrambled; it makes perfect sense when you can see her face and flapping arms, but some of her best stories won’t, alas, work at all when I come to transcribe them from my tape.)

Are there paintings, then, that she has come to dislike? “It’s not so much that. It’s more that it’s so big. You realise how long you’ve been busy.” She’s proud of the retrospective, but size doesn’t necessarily matter to her these days. “When I had a show at Moma in New York, people said: there’s nothing more you could ever want! And it’s true that, at a different stage in my life, I might have thought that. But as you get older, sometimes it’s the smaller spaces, the shows almost no one saw, that seem quite special.”

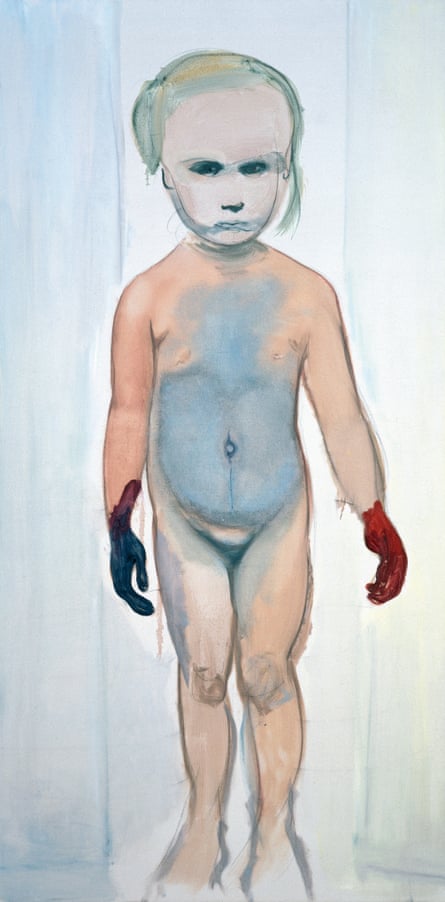

Working on this show, what astonished her most was to see her paintings again in their true colours: “I’d started to have the reproductions in my head instead of the painting, so when I finally saw them again, I was surprised.” She pulls the catalogue for the show – it is called The Image As Burden – across the table towards us. On its cover is The Painter, an oil from 1994 of a small, naked child whose hands are covered in what is surely paint, but could just as easily be blood. “Even after all these years, I’m still surprised when I see it. I think: is it that cold? That bleak? The reproductions – even this one – are too pink, too cute.” She stabs at the picture with a finger. “Aaah! I can’t stand it! The real thing is more green.” Isn’t this, though, the magic of paint? The canvas, the light, the human eye; it’s alchemy, and we should accept no substitutes. “Yes, of course. That is what is exciting.” Her eye flicks back frustratedly to the catalogue. “Still, it’s strange the way colour is so hard to remember.”

Dumas is not a particularly prolific artist, but she paints quickly and her gestures are fast (she favours oil, which takes a while to dry, so she can smudge things later if necessary). When she first picks up her brush, she has to work through the kitsch feeling – the sheer ridiculousness and grandiosity involved in standing in front of a canvas – but once that has passed, she can produce a major work in a single night. “The biggest difficulty for me is to be able to concentrate properly,” she says. “Every time I start up again, I think: I don’t know if I know how to make a painting. I always imagine I’m going to change my whole life, to start writing books instead. But the good thing now is I know I will feel all these things [in advance]. Otherwise I would be desperate.”

Does it matter what other people say? Yes. She’s interested in critical responses to her work: she put the catalogue for the retrospective together herself, and it includes as much as she could squeeze in of what the critics have written about her down the years, irrespective of whether she agrees with their interpretations. Nor does she flinch from criticism in the studio. “If my assistant tells me I’ve done a clown or something, I don’t mind at all. I want to know.” Admittedly, nerves do set in when she works on political paintings. Who could depict, as she has done, a group of Hasidim standing in front of the Israeli separation wall as they prepare to pray at Rachel’s Tomb nearby, and not tremble inwardly at the likely reaction? (The provocation of this painting is the separation wall’s similarity, in her rendering, to the Western Wall in Jerusalem.) But then she tells herself: “Well, Picasso had his Guernica. I’ve got something I want to express, and I must express it.” She flashes me a mischievous look. The look says: yes, I just likened myself to Picasso. She knows this is outrageous, but some other, more determined and resolute part of her thinks: why not?

Dumas was born in Cape Town in 1953, but grew up in Kuils River, a semi-rural area 15 miles outside the city, where her father ran the family winery. The family was Afrikaans-speaking, gregarious and loud. “I didn’t want to leave them at all,” she says. “When I moved to the Netherlands, I missed Sundays, which was when we would really argue and discuss things. We knew we cared for one another, so you could lose your temper and it didn’t matter.” She had two older brothers, Pieter and Cornelis, but three of her grandparents also lived at the farm, and so, too, did two cousins, Annatjie and Sandra, who were taken in by Dumas’s mother after their father died.

Her own father died when she was 12, but not before he’d noticed his daughter’s interest in drawing. “My parents didn’t think I was an artistic genius. It was more that they thought it was peculiar, the way that if we went to the Kruger [national park] I would not be looking at all the animals, I would be drawing, retreating into my own world. They weren’t discouraging, but they didn’t overdo it [praise-wise] either.” She knew she was different. “I was a bit of a tomboy. I didn’t like to sew or to cook; I didn’t feel affiliated to the womanly arts.” At her boarding school in Stellenbosch, a rather strict establishment, she was sometimes punished for her unladylike behaviour, for walking barefoot and wearing her father’s old dressing gown. “Oh, I hated it!” she wails, comically. “But at least it was more academic than the local school. At least art was a subject.”

She chose an English-speaking university in Cape Town over an Afrikaans one, but the transition was hard. She knew very little of the world: television did not arrive in South Africa until 1976, the year she left for the Netherlands. In an essay she has written for the catalogue of The Image As Burden, she describes her student years as a period of firsts: “I was 19, it was the year 1972, and I’d never sat with a person of colour following the same classes before. Never had dinner with a Jewish or Muslim family before. Was introduced to the poetry of Allen Ginsburg... Was introduced to the films of Ingmar Bergman, Resnais, Godard… And the plays of Jean Genet, Tennessee Williams and Athol Fugard.” How soon into her degree did she know she would be an artist? “I took things step by step. At school, I didn’t think the fact I liked to draw made me an artist. I never thought I was good enough. I thought about being an art therapist. But then at university I thought: Ooh, what is this? Jackson Pollock! Picasso! Lichtenstein! Intellectually, you wanted to be avant garde, even if you weren’t sure you had the power to do it alone.”

At the end of her degree course, a single bursary was available for a two-year study period abroad. She won it. She chose the Netherlands – she was to teach at Ateliers ’63 in Haarlem, an artist-led postgraduate programme – because of the link between Dutch and Afrikaans; New York seemed “too big and ambitious”, and Britain was a country loathed by her parents for being South Africa’s former colonial power.

In some ways, it was a relief to leave South Africa. The townships were burning; censorship was rife. Apartheid was the impossible subject but equally, what kind of artist could ignore it? “[In the Netherlands] I read all the books that were banned,” she says. “As a woman, I could also walk alone at night and not feel scared, and that was fantastic.” But she was also desperately homesick, and though she could read Dutch and make herself understood, there were baffling gaps between the two idioms. “Afrikaans is more rhythmic, more like slang, while Dutch is so prim and proper. I don’t dislike Dutch, but I didn’t understand the humour, and when I read art reviews, I was never quite sure if the critic liked the art, or not.” Did she feel like an outsider?

It wasn’t as simple as that. “In South Africa, I was Afrikaans, but as the politics developed, obviously you didn’t like certain aspects of your culture. The South African culture they [the white minority] wanted to protect for me, I didn’t really feel part of either.” She smiles. “Also, in Cape Town, there was only one art gallery, and you had to pay to exhibit there, and no one ever bought anything, they just came for the cheese and wine.” In a way, her status as an exile was helpful, a kind of protection against criticism and failure. “I always thought: I’m not going to stay anyway! If it all fails, I’m going back to my mother.” What language does she think in now? “With my partner [the painter Jan Andriesse, with whom she has a 25-year-old daughter, Helena], we flip between Dutch and English. But if I’m writing about art, I think in English.”

Her career, once it began, built steadily if not spectacularly: “My generation is Julian Schnabel, and he got known so quickly, just like Cindy Sherman and Barbara Kruger. It took me longer.” Early on, she worked in collage as well as paint: The Image As Burden includes several examples, perhaps the most significant of which is Love Versus Death (1980), in which two “clue-strips” consisting of various photographs and newspaper clippings (Steve Biko is among them, and so, too, is Peggy Guggenheim) suggest ways of reading the work’s central panel of drawings. By the mid-80s, however, she’d given herself over to paint, and in particular to portraits. These portraits, painted from photographs, often news clippings, rather than life, fall into two groups: the living and the dead, the anonymous and the famous. But her palette is consistently ghoulish, her subjects’ bodies bruised and bent, their skin a liverish green or a gallows blue. Here are swollen pot-bellies and ribs that look like xylophones, wattled chins and twisted – even broken – necks. Some hold extremely graphic sexual poses. Others are blindfolded, or bound in duct tape. And every so often, there comes, transfixingly, a notorious face: Osama bin Laden, Naomi Campbell, Phil Spector with wig, and without. Dumas’s portraits tend to be contextless, her subjects’ faces and limbs floating disembodied, arranged for maximum drama on a washed-out backdrop.

More recently, though, she has produced bigger, more daring, explicitly political canvases in which context is all: a series of oils (Against the Wall, 2009) inspired largely by events in Israel and Palestine; two paintings, both called The Widow (2013), in which Pauline Lumumba can be seen walking bare-breasted through the streets of Léopoldville, in mourning for her dead husband, Patrice Lumumba, the former prime minister of Congo who was executed by firing squad in 1961 by Katangan forces.

Her feelings about her sale prices are mixed. “When people first started to buy work, it was wonderful that someone wanted something. But in the beginning, of course, there were no auctions. People only bought it if they really liked it. Then that all changed. When I was described as the highest-selling woman artist, it had a strange force. In South Africa, you weren’t proud to be an artist: it felt egocentric. I was a bit ashamed. The attitude [there] was: that’s just a drawing. So…” Her prices were a validation? “Yes, and it’s unfair when people say the political paintings can’t be taken seriously when they go for so much money. But still, I was happiest when I had enough money on which to live and no more…” She would rather her work went to institutions than collectors (in 2012, for instance, the National Portrait Gallery acquired her 2011 portrait of Amy Winehouse, Amy-Blue, for £95,000).

Does she feel that the female artist must defend her work (and perhaps her prices) in a way no man would ever be required to? “It [sexism] is like racism or homophobia. Progress is made, and you think: oh, this is going well. But then you remember: oh, shit. People like Georg Baselitz still say women can’t paint. Male artists of a certain generation still have a way of speaking that says: I’m the best. Women still accept smaller gallery spaces more readily than men. I’m still accused of being the token woman.” She falls into sarcasm. “But I’ve never slept with any museum directors, honestly!”

She stands up. Her tea is untouched, and now freezing cold. “So let’s have some wine, yes?” She reaches into the office fridge for a bottle of white, pours, swigs, and then we talk for quite a long while about Oscar Pistorius and Shrien Dewani, both of whom, she agrees, seem like natural subjects for her. She’s fascinated in particular by Dewani, whose trial in South Africa recently collapsed, and pumps me for information. “The Dutch don’t have a Sunday newspaper!” she says. “They don’t have the sex page, or whatever you call it.” This national failing has her shaking her head vigorously.

After this, she takes me into her studio next door. There are three rooms, two in which she works, and one that contains her archive, its shallow drawers stuffed full of all the things she has torn out of magazines and newspapers through the decades. Tipsily, we shriek with laughter at a cartoon pinned on a wall. (A man says to a woman he has met at a party: “Your work is surprisingly strong. Have you always been a woman?”) “Yes, take a picture of it!” she instructs.

Earlier, she was insistent that she had not made any new work for a year, the retrospective having taken up so much time and energy. But now I see that this is not quite the case. On a wall are the latest drawings for her Great Men series, a collection of portraits of gay men (the Tate show will include drawings of Alan Turing, Tennessee Williams and Tchaikovsky). She looks at me looking at them – I’m drawn especially to her young Auden and to her Francis Bacon, both of which seem to capture something of their very essence – and when I turn around, I can’t help but notice that she is wearing quite a daffy smile. Dumas doesn’t, unlike some artists, simply accept compliments as her due; it’s clear that they still have the power to thrill, and on receiving a genuine one she radiates graciousness, relief and a kind of simmering excitement. You feel as though you could toast your hands on her. Her company is eight times as intoxicating as her wine, and when she finally tips me out into the foggy Amsterdam night, I find that I miss her, for all that our acquaintance is only two hours old.

Marlene Dumas: The Image As Burden is at Tate Modern from 5 February to 10 May

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion