The shadow of a man slips down the street in broad daylight, tall, dark and mercurial. It slithers over kerbstones, sidles up walls and passes straight through the oncoming people. We recognise it as a shadow, but not as an actual person; in fact it could be anyone, although it might be possible to guess from the head shape, the watch strap, the trademark spectacles and loose shirt that this is the artist Mark Wallinger.

This is the artist? Well not quite: it is only the shadow he casts patrolling Shaftesbury Avenue. The film splits their unity, so to speak, in two. We cannot live without a shadow, and yet this one seems to gather a superior identity all of its own. As Wallinger walks along, his sandals become tangled up with the shadow until it seems as if the shadow takes over, has more authority in its powerful stride than the real feet, apparently following after rather than generating the shadow. The two of them are no longer equal.

Wallinger, brilliant man, presents a riveting sequence of meditations on identity in his new show at Hauser & Wirth. Just as this film makes one ponder the strange quiddity of shadows – that they are caused by us, and in some profound sense representations of us, and yet neither self-portraits nor even quite images of us – so the black-and-white self-portraits in the opening gallery are not conventional depictions either.

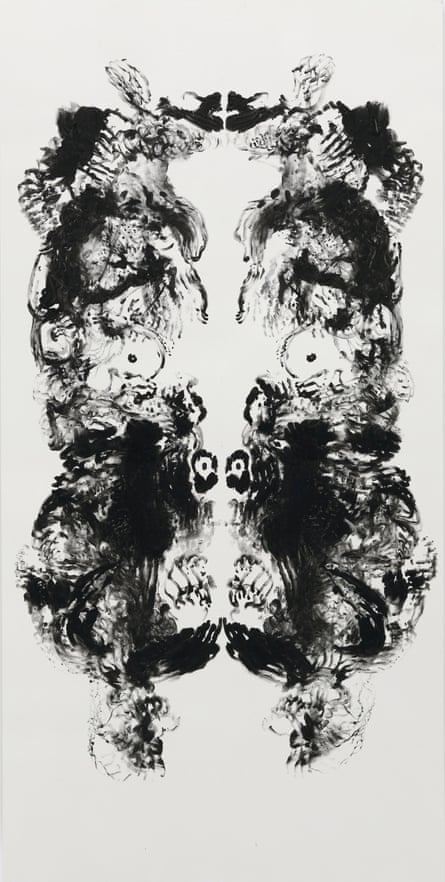

Vast canvases, twice Wallinger’s height and arm span, look at first like gigantic Rorschach tests; or at least this is the immediate association (Rorschachs being all about visual association and our compulsion to find the figurative in the abstract). Look into them and you wonder what they are – and more significantly where the artist is within them? Of course we will all read them differently, and each response, according to Rorschach, is supposed to give some telling trace of our own personality. Every viewer is both exposed and implicated here.

What do they look like? I saw a hilarious Edwardian face with mutton chops and popping eyes; a figure in mid-plié; a glowering black beetle, a shivering and vulnerable wraith. Cartoon speed marks, complex arabesques, two praying apes coming face to face: it is worth remembering that Wallinger began as a painter.

But these paintings are made with his hands, not a brush. They resemble ab ex canvases to some extent – Franz Kline without the brush swipes – but are far more intimate in their method, irresistibly proposing the manner and progress of their own making. For there must have been an immense effort involved in making one side of the painting look so much like the other. And here is where self-portraiture enters in.

Rorschach patterns involve blotting a page with ink and folding it in half to make a mirror image. They are effectively accidental and contingent, whereas Wallinger’s paintings are exactly the opposite. No matter how wild they may look, these paintings are intensely composed, exacting and subtle. They operate as group self-portraits, in a sense, because we all see something different in them and yet Wallinger is clearly represented in that singular principle: the artist as democratic philosopher.

As a coda, another of his deflective self-portraits is on show at Dulwich Picture Gallery: an enormous capital letter I cast in steel. It’s in Times New Roman (the common default typeface) as if representing all the Is in the world, except that this one is exactly Wallinger’s own height.

I – the word, the pronoun – is the simplest visual sign of the self: a child knows what it means. But an adult might say the concept was infinitely complex. And that is the crux of this sculpture. It is just a big I, pure and simple. But what is an I, how does it sum up my identity? These are the very questions we ask of self-portraits.

There is an autobiographical strain to the Hauser & Wirth show. In one gallery, Wallinger has reprised the famous sign outside Scotland Yard using mirrors, so that the three faces revolve round and round, seeing everything, reflecting everything, but blank as a mirror, that passive thing that only flickers into life when something comes before it. The sign is hoisted so high above our heads that we can scarcely see what it sees except by standing, necks wrenched, directly below.

The political implications are immediately clear; but there is more. In 1986, Wallinger was beaten up during a skirmish between the BNP and Sinn Féin at a London demo. His head (and his glasses) were smashed. The police promised to help but instead paraded the suspect thugs before Wallinger quite uselessly, since he could not see, and they never took him to hospital. For mirrors, read CCTV cameras – seeing everything, and yet so blind.

Superego, as the work is titled, happens to be installed directly opposite the very police station where Wallinger was taken. “Apprehension” is the word he uses of that day, in the gallery guide; what a mordant triple pun.

An oak tree, changing through the seasons, appears on four screens around the viewer in the final room. The oak stands on a traffic island. Each separate film revolves around the tree at slow driving speed (the camera is in fact an iPhone Blu-Tacked to Wallinger’s car window) so that one has the sense of standing at the centre of many circling movements all at once. The work, named after a mechanical model of the solar system, is titled Orrery.

The oak tree stands, of course, for our sceptred isle (though it is also the New Fairlop Oak in Barkingside, where Wallinger learned to drive). You see the cast of his thought. The minutes pass, the sun shifts, the day turns, and with it the seasons. We turn on this little island, and in our lives, as our planet turns in time within the universe. But we are at the centre of it all. This is classic Mark Wallinger: the eloquence of his ideas as condensed as a sonnet, and expressed in the humblest of visions, in this case an oak on an Essex roundabout.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion