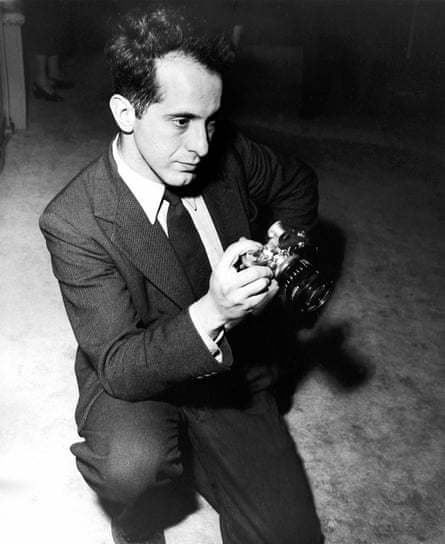

Robert Frank, who has died aged 94, was to the photography of 1950s America what Walker Evans was to the 30s and Robert Mapplethorpe to the 70s. His black-and-white images captured the ignored and rejected lives of individuals existing on the edge.

In 1957, Frank met the beat writer Jack Kerouac at a party in New York and showed him a sheaf of photos he had recently taken on road trips around the US. Kerouac offered to write an introduction for what became Frank’s best known book, The Americans, published in Paris in 1958 and in New York the following year. Kerouac noted the coffins and jukeboxes that litter the work until “you end up not knowing any more whether a jukebox is sadder than a coffin”. He concluded: “To Robert Frank I now give this message: You got eyes.”

The Americans covered the loneliness of empty streets and solitary individuals: the blond at the Hollywood movie premiere; the half-hidden man leaning on his cane beneath the broken-down stairwell of a rooming house; the baby who has fallen off her cushion on to the bare boards of an empty cafe.

Travelling, eating and sleeping are the habits of most interest: the transport of variously hatted pensioners in a Florida charabanc; Hell’s Angels; Chevys at a drive-in; a gleaming Lincoln sporting the huge slogan “Christ Died For Our Sins”.

Religion frequently has a sinister dimension in the photographs, as in his images of moonlit crosses beside Highway 91, a Jehovah’s Witness selling copies of Awake! and the Disney-style turreted castle headquarters of the Mormons at Salt Lake City.

Frank was born in Zurich, to a Swiss mother, Regina Zucker, and a German Jewish father, Hermann Frank. Hermann was made stateless at the end of the first world war and, together with his two sons, Robert and Manfred, obtained Swiss nationality only at the end of 1945. Frank had a comfortable upbringing, attending private schools in Zurich.

He was apprenticed to photographers in Zurich, Geneva and Basle, and worked for Gloria Films as a stills photographer before launching himself as a freelance and moving to Paris. In 1946 he produced his first, handcrafted album of photographs, 40 Fotos. He was already showing fascination for detail: lines of washing and chimney stacks, pots and spoons in a kitchen, the lonely outsider in a crowd.

In 1947, Frank took the boat to New York, where he began working for Alexey Brodovitch, the art director of Harper’s Bazaar magazine. He freelanced for the major picture magazines, including Fortune, Life and Look. Like Irving Penn in approximately the same period, he found Peru inspirational; the images he shot there found their way into another handmade book of images. In New York he met the curator Edward Steichen, who included Frank’s work in the group show 51 American Photographers at the Museum of Modern Art in 1950.

That year Frank married the artist Mary Lockspeiser. They settled in Manhattan and had two children, Pablo and Andrea. Frank had returned to Europe in 1949 and in the early 50s, shooting mainly in Paris, but also in Barcelona, Madrid, London and the Welsh valleys. He eschewed tourist attractions, photographing always on the margins: an elderly violinist begging at Victoria station; circus children with dirty faces and torn, wrinkled clothes; posters and chairs abandoned in derelict outdoor settings. All were photographed, including the night shots, using available light.

In 1956 Frank collaborated with the photographers Werner Bischof and Pierre Verger and the author Georges Arnaud to create a book of Latin American images, Indiens Pas Morts (literally, Not-Dead Indians), published in Paris. It was there that Robert Delpire published Les Américains, which became The Americans.

With a Guggenheim fellowship Frank had roamed the US in 1955, accompanied by his family on two long trips that took in Michigan, Georgia, Miami, Reno, Salt Lake City, Illinois and Florida. From the 28,000 images he shot, Frank picked 83 for inclusion in the collection, which became the most influential photography book in the US in the postwar period.

In 1961, Frank received his first solo show at the Art Institute of Chicago, called Robert Frank: Photographer. Another followed at the Museum of Modern Art in New York a year later. He preferred to write or say as little as possible about his pictures. In 1951 he said: “When people look at my pictures, I want them to feel the way they do when they want to read a line of a poem twice.”

His motivation was to make the work “move – or talk – or be a little more alive”. To this end, and by the time The Americans was published in the US, he had switched medium and was primarily working in film. Pull My Daisy (1959), made with Kerouac and his fellow Beats Gregory Corso and Allen Ginsberg, was widely praised for its apparently effortless spontaneity. Frank’s co-director, Alfred Leslie, later revealed that everything had been meticulously planned, rehearsed and executed.

His other shorts included The Sin of Jesus (1961), an adaptation of an Isaac Babel story, and Me and My Brother (1969), which starred Ginsberg and Peter Orlovsky and had a script co-written by Sam Shepard.

In 1972, he directed his best known film, Cocksucker Blues, which followed the Rolling Stones on tour, drugs and sex sessions included. Mick Jagger was reported to have told Frank: “If it shows in America we’ll never be allowed in the country again.” A court case ensued to decide whether copyright resided with the director or the subjects. The verdict limited the film to a restricted number of public screenings. Frank’s best known subsequent films were Keep Busy (1975) and Candy Mountain (1988).

In 1969, he and Mary separated, and soon afterwards Frank settled in Nova Scotia, Canada, with the sculptor June Leaf, whom he married in 1975, and who survives him.

In 1972, he published The Lines of My Hand, which he described as a “visual autobiography”. It sold in far fewer numbers than The Americans, and received a mixed critical response, but is widely admired by photographers and students.

In 1974 Frank’s daughter, Andrea, died in a plane crash. His response was to create complex collages composed of snapshots, postcards and scratched, doctored negatives. He also made a film, Life Dances On (1980), in her memory and, in 1995, founded the Andrea Frank Foundation, to award grants to artists. His son, Pablo, died in 1994, having spent a number of years in a psychiatric institution. Frank’s subsequent work became darker, the former preoccupation with dereliction and despair now explicitly linked to intimations of mortality.

He grew increasingly reclusive but emerged for specific commissions, such as the 1996 music video for Patti Smith’s Summer Cannibals. He continued exhibiting and curated a major retrospective of his work, entitled Moving Out, for the National Gallery of Art in Washington in 1994. Tate Modern in London held the first major UK exhibition of Frank’s work in 2004. The 50th anniversary of the publication of The Americans was celebrated with a new edition in 2008, for which Frank reframed and cropped many of the images.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion