Dusk at Ostend, and a black pall descends on the eerie lighthouse. The skyline is starting to fade, the shoreline dwindles to a glimmer. The town lies still, but out at sea the waves are heaving like a sleeper troubled by dangerous dreams. And this is where we are, where the picture puts us – out here in the drowning darkness.

The Belgian artist Léon Spilliaert (1881-1946) was probably not more than 20 when he made this frightening image, using diluted black ink, paintbrushes and coloured pencil. It feels as if he was standing right there in the undertow. The pull of the tide was lifelong for Spilliaert, who patrolled this stretch of coast every day, walking out across the Ostend sands before dawn, at dusk and in the midnight hour. He knew this sea by heart.

But I did not know his work until a couple of years ago, except for a single self-portrait in which he appears like a ghost in a sepulchral parlour, and a lone house reflecting black in a twilight dyke. I didn’t know how to say his name – the emphasis is, pleasingly, on the last syllable, pronounced “art”. I had only the haziest sense of his life or dates. But then I came across him in the oddest way.

I was looking for images of deserted beaches for On Chapel Sands, a memoir I was writing about my mother, who was snatched from another long, flat shore as a child. Most European artists of the period can’t resist parasols or sails or paddling children. Of course there was Turner, from first to last. But I was trying to find an artist who saw the beach somewhat as I did, as a stage from which people might suddenly disappear. Spilliaert’s beaches were not only dramatically empty, they seemed to hold the sense of a vanished presence, of uneasiness and even threat.

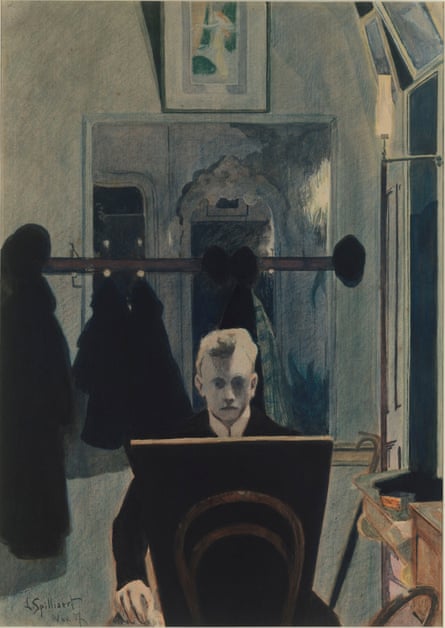

His paintings appeared as timeless as the shorelines themselves – sand, sea and sky in successive bands of abstraction. And he took them even further from the marine radiance we associate with seaside pleasures into the monochrome land of night. Which was where Spilliaert himself liked to live, or so it seemed to me from that startling self-portrait I had seen in the Metropolitan Museum in New York. Here was the young Spilliaert, with his trademark quiff and narrow suit, sitting with a drawing board before a mirror that shows distempered walls, black windows and another dark mirror behind him: a wraith in a box of shadows.

But to look at his seashores in anything but reproduction was almost impossible. Spilliaert is barely represented in museums outside Belgium, and scarcely at all in Britain. His art is mainly hidden away in private collections. To see it in reality meant travelling to Ostend, where he lived and died, and tracing his footsteps through the night.

For Léon Spilliaert is the great night bird of modern art. Restless, insomniac, and suffering from stomach ulcers from a very young age, he would rise in the small hours and walk the dead streets to the long promenade where Ostend meets the shore. His art is captivated by the unnerving solitude and silence. Image after image shows the empty seafront, the lone gaslights along the pier, the vertiginous steps dropping down to the wide blank sands, the black sea turning over and over.

His beaches glower in the crepuscular gloom. Coastal defences shear away at violent angles. Paths, arched colonnades and stone terraces hurtle towards the vanishing point. His palette runs from silver twilight, lead grey and sepia to obliterating black, with only the occasional touch of light in the moon, or a lamp’s halo. There is nobody there (except Spilliaert).

The artist was born into a family of shopkeepers in central Ostend. His grandfather had been the lighthouse keeper, but his father was a perfumier with a grand storefront on Kapellestraat, still the main shopping street. He also owned a hairdressing salon, which his son painted in 1909. In the low glow of a candelabrum, coats and hats dangle from pegs like dead people. Clearly, there are still customers, but the scene is so dim it feels like the middle of the night.

At school, Spilliaert studied the philosophy of Nietzsche and Schopenhauer and began to read the claustrophobic stories of Edgar Allan Poe. At the age of 18 he started a degree at the Academy of Fine Arts in nearby Bruges, but illness seems to have stymied his plans and he never finished the course. Perhaps by way of consolation, his father took Spilliaert to the World’s Fair in Paris, in 1900, and bought him the large box of coloured pastels that is now in the Mu.Zee in Ostend. He used them as subtly as Seurat, leaving the white paper blank for a pencil of light stealing across a street or the glowing disc of the moon. Grey, black, Prussian blue, ultramarine – all the dark pastels are worn down, the warm colours almost untouched.

To reach his home town, you must take the coast train from Bruges, where the guard consults a timetable glued inside his hat to confirm the correct platform. The station turns out to be so close to the sea that boats are moored right next to the platform. You exit through a magnificent Roman arch, a surviving fragment of the neoclassical grands projets of Leopold II, so much of them destroyed in two world wars.

Arrive by night, however, and Spilliaert’s Ostend is immediately visible. Here are his visions of boulevards as dark canyons ending, abruptly, in depthless black water. Here is the sea wall veering sharply across the dark shore. At the far end of the night beach, more than a mile out of town, is the set of steep, plunging steps that appear in Vertigo, one of his most famous paintings to Belgians. A faceless figure in black clothes crouches on one perilous step, looking out to sea, her funereal veil unfurling like a howl in the air.

Ostend, in winter, is pure Léon Spilliaert. The streets are empty, like some perpetual closing day, or as if the population had all departed. The immense beach is deserted, bar the occasional dark speck moving through the sea mists. Night falls on the tide, and you walk out to its freezing edge – solitary, wave-lapped, out of time and place. This was his gift, this exhilarating sense of estrangement.

It could be Biarritz off-season, the perfect sands raked every morning, the grand hotel with its palm court and elegant glass doors opening straight on to the front. But Ostend is extraordinarily distinct. For running all along this front is the uninterrupted surprise of a neoclassical colonnade, column upon column, arch after arch, holding dark shadows within. The very structure that Spilliaert painted many times – at dusk, in darkness, or perhaps with an occasional light shining through one opening, its source unexplained – remains as startling, almost, as his pictures.

In the forthcoming Spilliaert show at the Royal Academy – astonishingly, his first in Britain – visitors will be able to see The Royal Galleries at Ostend, from 1908, in which the artist positions himself at the precise point where the stone pillars seem to zoom towards the extreme vanishing point of a palace gate in the distance, in a race with the tide. The view is nearly parallax. Anne Adriaens-Pannier, a leading Spilliaert scholar and the show’s curator, believes that “the reality of his living, breathing home town became like a fantasy”. She quotes a letter he wrote in 1920, after returning from one of his rare trips away. “I belong here so much. I am living in a real phantasmagoria… all around me dreams and mirages.”

One such mirage, as it seems, is the curious sensation that there are two colonnades running in parallel. And so there are – two endless corridors, adjacent to each other and separated only by a glass partition, which materialises as an enigmatic reflection in one of Spilliaert’s paintings. You could, and still can, take either promenade according to the wind and weather. On one side is the sea, for Edwardian convalescents in need of bracing air; on the other is a racecourse – once named after Napoleon, later Wellington, after Waterloo – still boasting equestrian statues of Leopold. A paddling pond stands cracked and empty, and the ornamental iron railings are long gone, smelted for armaments by the Germans during the second world war; the seagrass grows wild and tall.

Spilliaert never got away to sea, never took the longed-for voyage. He watches departing ships cut a swathe through the waves, a white wake beneath an equivalent tornado of black steam. The Royal Academy will be showing his marvellously strange painting of a towering hull, front on, rising like a faceless monster from the dock. What’s striking, every time, is the sheer graphic zip and register of Spilliaert’s shape-making; and the perspective, in both respects.

He is always angling the space, cutting off a hat, emphasising a soaring vertical. Figures are way above or well below eye level, seascapes rise up to high horizons. He puts you in the water, as it seems, sometimes looking back at the remote lights of Ostend. Or he invents surrogates for himself and the viewer, strange proxy watchers on the promontory. Most captivating of all is the painting of a beach hut, casting its dark shadow on the sand, and looking out to sea, as if it too was a nightwalker roaming the shore.

The contemporary Belgian painter Luc Tuymans has contributed a hymn of praise to the Royal Academy show’s catalogue. Tuymans has studied Spilliaert, and clearly learned deeply from him. You can see traces of his own pale and etiolated images in Spilliaert’s quasi-portraits – some of them already based on the imagination, or photography, more than a century ago. The young Prince Leopold, spectral as if already dead; the rail magnate Andrew Carnegie, a ghost in sepia and black gouache, eyes like the scissored holes in a Hammer Horror portrait – both pictures surpassingly strange.

Tuymans alludes to the silent interiors of the Danish painter Vilhelm Hammershøi, and to the cityscapes of De Chirico. It is not evident that Spilliaert had seen the work of either artist, and his colonnades certainly prefigure the latter. The artist to whom he is most often compared is Edvard Munch; indeed, they were shown together during Spilliaert’s lifetime. The connection is most often made when rare figures make an appearance in the Belgian’s art.

A top-hatted spectre slips between dark arches. Two children watch the sea creep towards them, in dread, on the shore. In The Gust of Wind, a girl stands against iron railings on the promenade. Wind lifts her dress, revealing a flash of white petticoat in the gloaming, and her hair flares violently sideways. Look closely, and you see that her mouth is open in horror against the dying sky. To some eyes, this work makes Spilliaert the Munch of Ostend.

But the comparison is mainly confined to this painting. Spilliaert stands alone as an artist, and solitude is his special expertise. At the Mu.Zee, he is presented alongside James Ensor as one of the Two Masters of Ostend. Ensor, the senior artist by two decades, might not have appreciated the proximity. He was apparently irritated by the younger man’s attentions, complaining that he had once caught Spilliaert literally following in his footsteps round town. But they have nothing in common other than shopkeeper parents and an irreducibly Belgian strain of visionary imagination.

Spilliaert moved to Brussels for a while, illustrating the works of Maeterlinck and Mallarmé for a publisher. At the end of the first world war, aged 35, he married Rachel Vergison, and they had a daughter, Madeleine. She appears with him in a photograph from 1923, merrily digging the Ostend sand with a spade while he relaxes beside her (still in formal attire, of course). Marriage brought him serenity, but with paradoxical consequences. Spilliaert’s work was far stronger, alas, when he was unhappy. The more content, the more decorative his art. The girl from The Gust of Wind, loosely adapted, even appears on one of his father’s perfume bottles.

In later life, the artist took to painting trees as if they too were lonely beings. But almost all of the works to be shown at the Royal Academy were made before 1918. A single bed, jammed between dark window and oppressive wardrobe, is covered head to toe in a white sheet: is there somebody, or nobody, or a hopeless soul beneath? Glass flasks gather hugger-mugger on a mantelpiece, dominating the parlour, and yet so diaphanous they too could be a mirage.

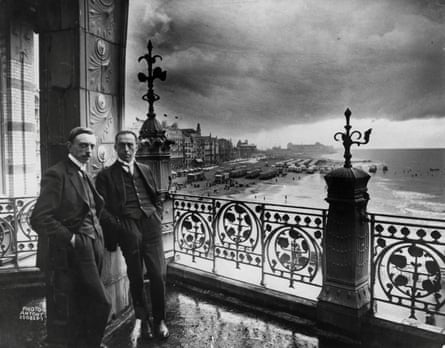

Period photographs in the grand Thermae Palace hotel on the front show views of Ostend in Spilliaert’s day. Ladies in long dresses, nannies with perambulators and whiskered gentlemen are shown sitting where we sit today, or walking exactly where we still walk, watching the ever-changing performance of the tide. Spilliaert himself appears in one shot, standing on the balcony of the old Kursaal concert hall and casino, in wing collar and three-piece suit, staring down at the bathing machines below. He could be a tubercular Edwardian taking the curative air.

To see this is to be reminded of just how weird and wild and modern Spilliaert’s self-portraits are, where he shows himself in monochrome, from below, or in collage, watering his ink to a translucent wash and gluing coloured paper to the page. He haunts the dark bedroom, stands before the black mirror, electrifying eyes touched in with blue pencil. In an extremely outlandish self-portrait from the Mu.Zee, one eye is occluded, as if blind, while the other is an owlish orb in a gnarled old head, brought back into reality only by the ormolu clock and starched wing collar.

This image will be on view at the Royal Academy, along with 80 works drawn mainly from private collections. This was Spilliaert’s fate, along with so many artists through time: he was patronised mainly by the thrifty middle classes, not by public museums. His great champion, the Belgian critic and poet Émile Verhaeren, died in an accident in 1916; and James Ensor, of course, used up most of the oxygen in Ostend culture. He even outlived Spilliaert, who died of heart failure at the age of 65.

This is a vital opportunity, then, to catch sight of his dark and startling art in all its precise originality, and to understand him as more than a painter of the cold North Sea. For Spilliaert’s great works always transcend the visible. In one vision he is far away along the shore, alone in the darkness, looking back at the Kursaal across the water. Perhaps he is even in the sea itself.

The lights of the casino are conventionally reflected in the water. But the building itself is a suave and nearly abstract form, hovering beneath a pale moon like a spaceship about to lift off. It is 1907, and the Kursaal will one day be bombed, and replaced decades later by a modernist casino that looks exactly like this. Spilliaert never saw it, but he seems to have prophesied the future in this floating pleasure palace: an artist for our time, trapped in the Belgian past.

Léon Spilliaert is at the Royal Academy, London, from 23 February to 25 May, transferring to the Musée d’Orsay, Paris, 15 June to 13 September. Laura Cumming stayed at the Thermae Palace hotel, Ostend, as a guest of Visit Flanders