‘The contemporary city needs a full redesign,” purrs a seductive voice, over surging orchestral strings. “What if we removed cars? What if we got rid of streets? What if everything you needed was always a five-minute walk away?” The words accompany an animation depicting an oblong megastructure sprouting from a desert landscape, slicing through sand dunes and mountains in a continuous urban strip: a city of 9 million people, sealed inside a mirror-clad box. “A 170km revolution in urban living,” the narrator continues, “protecting the Earth’s most stunning nature, while creating unmatched liveability.”

Most cities don’t come with their own Hollywood-style trailers, but then most cities are not the Line. Unveiled in July, the project is the latest heady fantasy to emerge from the kingdom of Saudi Arabia’s marketing machine, garnering breathless headlines and torrents of clicks (its videos have 400m views and counting). The slick trailers promise a car-free, carbon-neutral bubble with its own temperate microclimate, where artificial intelligence will be “continuously learning predictive ways to make life easier”.

The city’s 500-metre-high glass walls drip with lush hanging gardens, a vision of hyper-nature taking over the buildings’ pixelated glass blocks, their facades etched with circuit-board motifs, as if the metropolis itself were a habitable supercomputer. The walls frame a deep canyon sprinkled with Edenic terraces, swimming lakes and picnicking couples, all floating above a high-speed rail line ready to whisk them along the urban ribbon, safely protected from the outside world.

If it looks like something from a Marvel movie, there’s a reason. The army of consultants commissioned to work on Neom, the $500bn urban region of which the Line is part, comprises not only urban planners but numerous digital artists from the special effects industry. According to a Bloomberg report, they include Olivier Pron, a designer who helped create the look of Marvel’s Guardians of the Galaxy films; Nathan Crowley, known for his work on the brooding Dark Knight trilogy of Batman movies; and futurist Jeff Julian, who worked on the apocalyptic extravaganzas World War Z and I Am Legend. The ominous dystopian undertone to the aesthetic of the project can also be partly explained by Saudi ruler Mohammed bin Salman’s apparent penchant for cyberpunk – a sci-fi genre, notes the Oxford English Dictionary, “typified by a bleak, hi-tech setting in which a lawless subculture exists within an oppressive society dominated by computer technology”. If ever there was an urban vision that embraced our end-of-days climate apocalypse, a petrodollar mirage of horizontal glass skyscrapers in the desert as the world burns, then this is it.

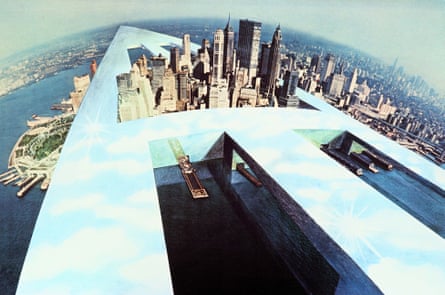

The plans for the Line were instantly compared to the Continuous Monument, a theoretical project drawn up by Italian collective Superstudio in 1969, which was not a blueprint for a smart city but a searing critique of the relentless urbanisation of the planet. Their collages of a glass megastructure, ploughing through desert landscapes, cutting across oceans and engulfing Manhattan, were intended to represent a “negative utopia”, according to Superstudio co-founder Adolfo Natalini, and stand as a warning against “the horrors architecture had in store, with its scientific methods for perpetuating standard models worldwide”. Another Superstudio member, Gian Piero Frassinelli, was rueful in a recent interview: “Seeing the dystopias of your own imagination being created,” he said, referring to the Line, “is not the best thing you could wish for.”

It may now be seen as a dystopian nightmare, the far-flung folly of an autocrat desperate for global approval, but the idea of building a self-contained linear city has preoccupied the imaginations of architects and planners for generations. The Line might bill itself as a “never-before-seen approach to urbanisation”, but the principles behind it have been proposed many times over – though never successfully realised.

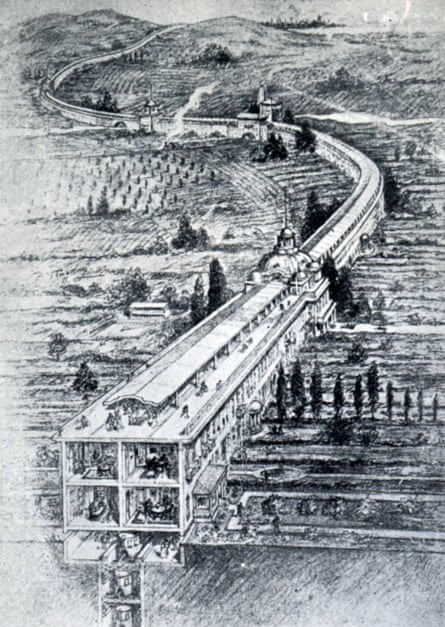

The origins of the linear city dream are usually credited to the Spanish town planner Arturo Soria y Mata, who first articulated the concept 140 years ago. Writing in 1882, in the Madrid newspaper El Progreso, he argued that the “almost perfect” type of city would be “a single street unit 500 metres broad, extending if necessary from Cádiz to St Petersburg, from Peking to Brussels”. His Ciudad Lineal imagined urban functions separated in bands either side of a central boulevard and tramway, “for every family its own house, for each house an orchard and garden,” the urban strip insulated by woodland on either side. Soria even went as far as founding a tram company and buying land on the outskirts of Madrid to test out his theory. But the surrounding land values soon inflated out of reach, and his experiment gradually became swallowed up by the city.

If history repeats itself first as tragedy, then as farce, the first tragic attempt to follow in Soria’s footsteps came in 1910 in the United States. That year, Edgar Chambless took a map and a ruler, and drew a straight line from the Atlantic coast to the Allegheny mountains of West Virginia, then on to the Mississippi, across the prairies to the Rockies, and down to the beaches of the Pacific. His line represented the path of a continuous street of two-storey houses, to be built atop a triple-decker stack of railway lines, with a promenade along the rooftops, leaving untouched expanses of countryside extending for miles around on either side.

“The idea occurred to me to lay the modern skyscraper on its side,” Chambless wrote. “I would take the apartment house and all its conveniences and comforts out among the farms by the aid of wires, pipes and rapid and noiseless transportation. I would extend the blotch of human habitations called cities out in radiating lines. I would surround the city worker with the trees and grass and woods and meadows, and the farmer with all the advantages of city life – I had invented Roadtown.”

Just like the Line, Roadtown was premised on the lure of convenience, and the idea that the messy chaos of the city could be corralled inside a singular, sanitised strip, with “rent reduced, taxes minimised, slums exterminated”. Chambless’s sales pitch sounds almost identical to the Saudi scheme, describing the linear city as a hyper-connected place, joined by modern communication and “arrow-swift” noiseless transport, with “telephones, telegraphs, teleposts, parcel-carriers, freight service, compact, punctual, prompt, accurate, enabling you to live along the line from part to part and from end to end, and be served with the best at the cheapest at all times, while sitting in your easy chair”.

Roadtown was enthusiastically backed by Thomas Edison, who donated his patents for moulded-cement housing, and the inventor William H Boyes, who gifted his monorail invention. But, as with Soria’s scheme, wider support was unforthcoming. Undeterred, Chambless continued to promote his project for the next two decades, entering his plan to the 1939 New York World’s Fair competition, suggesting that the fair itself should be built around transportation, with prefabricated buildings to prevent waste. His submission went unanswered, and he killed himself in 1936.

While Chambless’s vision was an embodiment of the American dream of freedom, mobility and man’s triumph over the land, the idea of the linear city was also taking root among radical architects of the Soviet Union around the same time, driven by a very different ideology. Mikhail Okhitovich, a constructivist theorist and town planner, rejected the centralised city as a product of capitalism. Instead, he championed the idea of “disurbanism”, plotting cities in the form of long ribbons of decentralised development, as a means of populating the country’s sprawling rural hinterland with self-sufficient settlements. Housing would be dispersed along linear routes, with communal dining, leisure facilities and employment centres at major road junctions.

Okhitovich put his ideas to the test in 1930, in a competition proposal for Magnitogorsk, an industrial city named after its “magnetic mountain” of iron ore. He imagined a network of eight 25km-long ribbons, along which the city’s resident-workers would live in individual “pod-houses” that could be easily reconfigured, the ribbons converging on a giant iron and steel works. Children would receive their own separate pods, with the aim of dissolving traditional family structures, while a divorce would no longer entail haggling over property – you could simply decouple your pods and go your own way.

But Okhitovich’s disurbanist thinking was rejected as economically crippling and politically dangerous. He was reprimanded by the politburo for speaking out against the Stalinist “cult of hierarchy” and sent to the gulag, where he was executed in 1937.

While Chambless was peddling Roadtown across America, and Okhitovich imagining urban ribbons snaking through the Ural mountains, the Swiss-French architect Le Corbusier, maestro of megalomaniacal urban plans, was busy drawing up a linear city of his own. In 1931, to mark the centennial of French rule in Algeria, the colonial government unveiled a new city plan for the capital, Algiers. Le Corbusier saw it as a sorely missed opportunity – and a promotional opportunity for himself to offer a more radical vision. Without any official commission, he concocted Plan Obus, a wildly implausible scheme that included a vast elevated highway winding between the hills, with 14 storeys of housing for the working class stuffed underneath it, like a kind of inhabited viaduct, with room for 180,000 people.

“Here is the new Algiers,” he declared. “Instead of the leprous sore which had sullied the gulf and the slopes of the Sael, here stands architecture.”

Le Corbusier’s brutal intervention in the landscape was strangely at odds with his professed appreciation of the local vernacular. “O inspiring image!” he wrote, stirred by the sight of the dense, cubic architecture of the city’s casbah. “Arabs, are there no peoples but you who dwell in coolness and quiet, in the enchantment of proportions and the savour of a humane architecture?” Yet, at the same time, his plan advocated razing more than half of the casbah to make way for a new business centre. Thankfully, his inflated colonial ambitions remained just that.

Despite these failures, linear city fever returned in the 1960s, fuelled by a wave of postwar techno-utopian optimism, and the firm belief that infrastructure could cure the ills of the overcrowded metropolis. In 1961, Japanese architect Kenzō Tange presented his scheme for the future of Tokyo Bay on national television, and, in doing so, triggered among architects a thirst for megastructures that would last for the next two decades. He proposed an 80km urban spine stretching across the bay, with city modules connected by three levels of looping roads, and modular buildings clipped on to the highway skeleton – a plug-and-play system that could be easily updated as and when needed. As with Roadtown before it, Tange’s plan was based on a firm belief that communication and mobility would inevitably shape the future city in linear form.

“Mass communication has released the city from the bonds of a closed organisation and is changing the structure of society itself,” he proclaimed. “It is the arterial system which preserves the life and human drive of the city, the nervous system which moves its brain. Mobility determines the structure of the city.” Just as the cathedral had stood at the symbolic centre of the medieval city, so would his “civic axis” provide the new organisational spine of the modern metropolis. In fine tradition, his proposals remained firmly on paper, although they went on to inspire the Japanese metabolist movement, which would conjure ever more feverish sci-fi plans, the linear city sprouting branches and blooming into vertical clusters of inhabited trees.

Back in the US, the evangelical belief in roads as the saviour of cities continued apace. In 1965, young architects Peter Eisenman and Michael Graves imagined a linear city that would stretch all the way from Boston to Washington DC, built on a podium of multi-deck highways. Depicted without any of the seductive finesse of Tange’s plan, the architects’ vision included a pair of spartan oblong blocks, one for industry, the other for housing, offices and shops, looking like an infinite extrusion of a generic office-cum-mall. The idea, they wrote, was that these urban “corridors” might join existing cities from Maine to Miami, like links in an endless chain.

“The final result could be a system which at once would send the longest manmade structure ever seen on earth snaking across its horizons,” cooed Life magazine, “and at the same time make it possible to conduct most urban activities within distances a man enjoys to walk.” The article noted that the linear form “would avoid any cross-town traffic jams” – conveniently overlooking the fact that the city itself would probably be one gigantic linear traffic jam, stretching up the entire eastern seaboard.

So will The Line succeed where other linear city dreams before it have failed, or is it merely set to repeat the mistakes of the past, on an epic scale? In the deserts of northwestern Saudi Arabia, a faint linear furrow is already visible from the air. Time will tell if it becomes anything more than that, or if it remains a line in the sand, an Ozymandian bookend to 140 years of deluded urban fantasies.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion