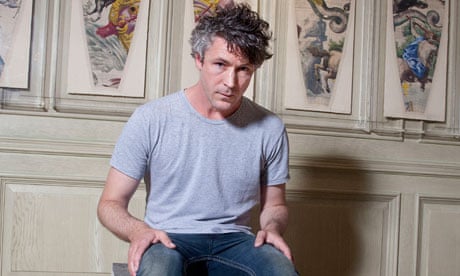

Although it's almost a showbusiness cliche, the notion of the performer grappling with shyness is hard to reconcile with some of the attention-grabbers who make loudest use of the old line. Aidan Gillen, the Irish actor who made his name as the outlandish Stuart in Queer as Folk, is different. He is shy, and not remotely in a self-dramatising way.

His arms form a protective tangle when he sits down in a Soho hotel, and his gaze flits back and forth to a spot awkwardly adjacent to my own. Then there's the conversation. Originally from Dublin, Gillen is the very opposite of the blarney-spouting Irishman. As he once put it, he hates small talk. But then he doesn't appear to be a great fan of big talk either. He speaks in haltingly pregnant sentences, filled with tormented pauses that make you feel as though each word has been given up only under sufferance.

Yet for all his "fumbling and mumbling", as he puts it, Gillen comes across as a thoughtful, perceptive and quietly amusing character, if you're prepared to withstand a few periods of disjointedness in the dialogue. Alas, many directors and casting directors are not. And for this reason, he says, he doesn't audition well.

"It might take me an hour to get to feel at ease with somebody. I don't find it easy to go into a room full of 10 people and give it all away. In the pilot season in Los Angeles I've done that a couple of times. You go in and read for all these shows, and I don't like it and I'm no good at it and it doesn't work for me."

Ironically, perhaps, Gillen's two best known characters – the priapic Stuart in Russell T Davies's Queer as Folk and Tommy Carcetti, the ambitious young mayor in The Wire – were swaggering, verbose extroverts. But in Shadow Dancer, a taut new psychological thriller set in Belfast during the Troubles, he is an IRA hardliner of few words and limited physical expression.

The film, made by James Marsh, who directed the highly acclaimed documentary Man on Wire, focuses on the tense relationship between Colette, an IRA informer (Andrea Riseborough), and Mac (Clive Owen), her British intelligence service handler. Gillen plays Colette's uncompromising brother, Gerry. He's full of praise for Riseborough, describing her performance as "fantastic".

"When I met James to talk about the film, I knew it was a supporting role – not that I have any aversion to playing a supporting role – but it became apparent that he was going to strip it back even more, which was interesting."

The result amounts to very little actual screen time, but it's a spare, still performance that lingers in the memory.

Initially he was wary about the subject matter. "I wasn't keen to be part of anything that was too provocative or incendiary," he says. "And I have turned some other things down for that reason. You know the peace up there is quite fragile, even though it's two decades in the making. It's a delicate situation and I don't want to be part of some grenade that's just rolled into the middle of that."

Although the film steers a largely neutral course, it's notable that, unlike several other films involving the Troubles, it does not sentimentalise or sanitise what active membership of the IRA involved. The paramilitaries are depicted as ruthless ideologues, locked in the righteous certainties of their beliefs every bit as much as they're trapped by their limited social horizons.

"Yeah," Gillen agrees. "I know. Of all the films made in the last 20 years that have the Northern Ireland conflict as a subject, this is probably the least sympathetic to Republicanism. Not by much, and yet it's still fair. It's quite heavy and profoundly sad."

A slender and youthful 44-year-old, Gillen grew up in Dublin, where he felt quite removed from events north of the border. It wasn't until 1990 that he first visited Belfast, when the atmosphere was still very tense. "You could run into anything," he recalls. But he developed a strong affection for the city and now he spends much of his time there, because Game of Thrones, the HBO sci-fantasy hit in which he appears as the scheming Littlefinger, is filmed at the old Harland and Wolff shipyards.

In the old days the shipyard was the preserve of a Protestant workforce, but now the film studio boasts mixed crews. "The change is quite amazing," he says. "There's still a fair way to go and the scars are deep, but it's come such a long way."

When Gillen was young, instead of looking north, he looked east, towards London. That's where the work was for aspiring actors, and that's where he went as a 19-year-old. He started out acting at the Bush, and slowly built up a portfolio of performances in well-received new plays at places like the Royal Court and Hampstead theatres. "There was a sense of urgency and risk," he says. "You get a buzz from that."

There were also periods of loneliness.

"They were formative years because I was spending a lot of time on my own. I was just about getting by with a few odd jobs and a bit of dole but I became quite dependent on the feeling I got from productions when they came along. That became something I became hungry for. And it's not real. They're make-believe relationships, and families and situations. But I guess that's what acting's about. It's not a new concept, is it?"

His first breakthrough on television was in the much-missed Screenplay strand, in Safe, a film directed by Antonia Bird. Since which he has divided his time fairly evenly between the stage, TV and film, with no more discernible pattern than a determination not to repeat what he's already done. Sometimes that has proved tricky because there are many parts for which he is simply not likely to be considered.

"For instance, I did this film a couple of years ago that I thought would be fun, and it was fun, a film called Blitz [a violent serial killer caper] with Jason Statham. I knew there was no way they'd come to me for that part, so I just put some shit in my hair, got my tracksuit out, and rolled up. If I just did the things that I'm going to get asked to do, they'd all be the same."

When he turned up as the cocky Carcetti on The Wire, it was said that he'd been cast on the strength of Queer as Folk. In fact, in a roundabout way, he owed the job more to Harold Pinter. The pair acted together in 1997, in Jez Butterworth's film adaption of his own play, Mojo. Their conversation over an off-set lunch brought new and prolonged meaning to the phrase "Pinteresque pause", with both men trading long silences.

"I don't feel obliged to speak," Gillen explains, possibly a little superfluously. "I can read people, and if the other person doesn't want to say anything, I'm fine with that. People say things when it's time to say them."

Some time later, David Jones, the late British director, was looking to cast Gillen in his New York production of Pinter's The Caretaker, and he called the great playwright to ask his advice. Jones told Pinter that Gillen was unable to fly over to audition, meaning that he would have to restrict his assessment of the actor to a phone conversation.

"Well that will be an interesting conversation," said Pinter, "because he's not going to say anything."

Primed by Pinter, Jones clicked with Gillen and cast him alongside Kyle MacLachlan and Patrick Stewart. The production was a success and it was Gillen, rather than MacLachlan or Stewart, who won the best reviews. One of the producers of The Wire, Robert Colesberry, saw Gillen's performance and recommended him to the show's casting director. Sadly Colesberry died before filming started on the third season of The Wire, in which Gillen's character was introduced.

"They told me, 'Well we have to cast you now, even if you're no good, because that was Bob's last wish.' That was their kind of humour," Gillen says with a grin that leaves you uncertain whether he shared it.

It must have been a challenge, I say, to arrive in the middle of an established cast, in a critically exalted show, and play such a confident character in a pivotal role.

"I didn't find it daunting," he says matter-of-factly. "I knew how good it was and I was very excited by the idea that we didn't know where it was going and by the prospects of working with people like David Simon, George Pelecanos, Richard Price and Dennis Lehane. And Simon in particular, his personality was so unlike the majority of people you might meet in film and television. The intelligence, dedication, humility, and just being interested in getting a job done and having something to say, and not any of the other stuff – the fame and fortune and where you sit in a restaurant. Maybe it's a Baltimore thing."

Gillen, who now lives on the west coast of Ireland with his wife and two children, liked Baltimore, where The Wire was set and filmed, and after his first season of working on the show he rented a terraced house and made friends with the locals. As regards socialising on the show itself, Gillen was not a member of the hard-partying group that included Dominic West, Clarke Peters and Wendell Pierce.

"I kind of kept to myself," he says. "Even within the drama, I tended to be with a certain group of characters. I did go out with them [the West gang] a couple of times but I don't like to go crazy when I'm working. I can see that it could have been really entertaining, but I kept it quiet. I stayed in an apartment building with a lot of those guys the first year and you'd be liable to have someone kicking on your door at three o'clock in the morning, 'We're going out man!'"

Gillen, it seems clear, is more of a staying-in kind of guy. With his saturnine looks, soft Irish accent and considerable acting talent, he could easily have slipped into a charismatic caricature many years ago. But instead he retains an integrity and humility that's almost surreptitiously charming.

When I tell him at the end of the interview that it's the photographer's turn to have her go, he looks like a man with a toothache in the dentist's waiting room.

"I find still photographs make me quite self-conscious," he says, as though a rolling tape doesn't. "I said to James Marsh, I'd love to be better at being still. It's something that I want to get comfortable with. Because then," he adds, breaking into a knowing smile, "I can say even less."

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion