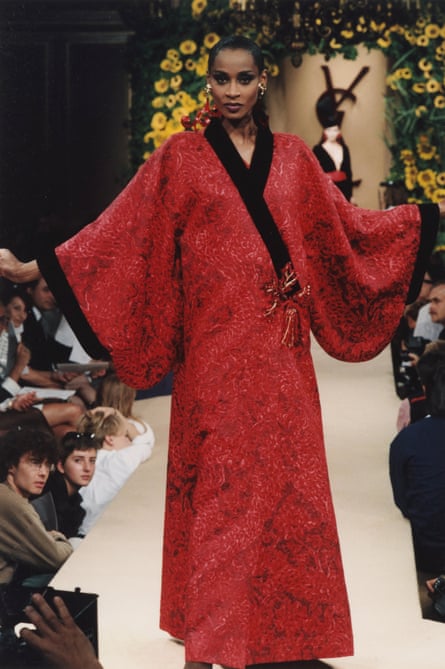

In the autumn of 1977, off the back of a succession of lavish collections inspired by the Ballets Russes and Spanish matadors, Yves Saint Laurent delivered his critically acclaimed “Les Chinoises” collection. It was inspired by China, a country he had never visited at that point and it coincided with the launch of the house’s iconic Opium perfume. This is the starting point for Yves Saint Laurent: Dreams of the Orient, a small but comprehensive exhibition that has just opened at the Musée Yves Saint Laurent in Paris.

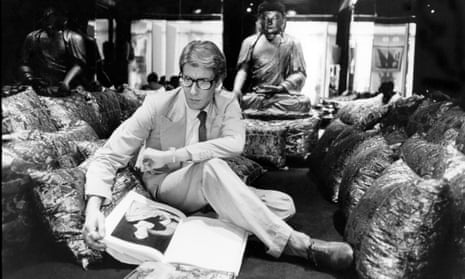

Covering this seminal Chinese collection, as well as a collation of examples that show Asia – or more specifically China, India and Japan – as an ongoing source of inspiration for the French couturier, it begins with the theme of Imperial China. We’re immersed into a sumptuous display of pieces from the Chinese collection that sit alongside Asian artefacts to emphasise the fact that Saint Laurent was a true connoisseur of the cultures that he was paying tribute to, explains curator of the exhibit Aurélie Samuel.

“He knew the culture, the history, the objects – sometimes it’s the motif or the design that inspired him, sometimes it’s the shape. For example, he knew the difference between a Han and Manchu garment.” This is evident in details such as the brocade of a fur-trimmed gold jacket mimicking the exact pattern of a Han dynasty jade vase or the shape of a blue and white Ming vase echoing in a 1983 embroidered qipao dress.

Upstairs in the India section of the exhibition, Samuel is keen to emphasise the subversive nature of Saint Laurent’s method of extrapolating from cultures. For example, by dressing women in Mughal prince robes and turbans adorned with a sarpech jewel that were traditionally the attire of powerful men, Saint Laurent was re-contextualising traditional dress and thus empowering women. “He wanted to assimilate Asian symbolism to reveal to a European audience,” says Samuel.

“I approached every country through dreams,” Saint Laurent once said and it’s this attitude of yesteryear’s haute couture world that feels somewhat fraught in today’s social-media-fuelled dialogue, where the risk of problematic cultural appropriation is only a Diet Prada call-out Instagram post away. Faithfully replicate a garment belonging to a culture not your own and you’re wrongly appropriating, but interpret that culture liberally, as Saint Laurent once did, and you could be accused of inauthenticity.

When it comes to the borrowing of chinoiserie motifs or Japanese kimonos in fashion, Saint Laurent of course is not alone, as evidenced in the 2015 blockbuster China: Through the Looking Glass exhibition which was centred on western designers and their interpretation of Chinese aesthetics. The result is that Qing dynasty dragon robes, mandarin collars, qipao dresses as seen on Maggie Cheung in In the Mood for Love and blue and white Ming vase patterns make up the mainstream lexicon of what people recognise as “Chinese” fashion. But Samuel argues that what Saint Laurent did was far from appropriation. “He didn’t want to copy China. He wanted to find the spirit of the culture and it’s a legacy and a tribute to these cultures.”

Certainly there’s no denying the sheer beauty of Saint Laurent’s pieces within the exhibition, as well as the faithful retelling of his inspiration source material, but walk past a bank of illustrations for YSL’s Opium perfume, launched in 1977, with every figure donning an Asian conical hat once known as a “coolie” hat and you would have to put it down to the context in which Saint Laurent was working.

In recent years, designers have wisened up to the intricacies of cultural appropriation and have largely steered clear of overt or obvious means of “exoticising” of Asian cultures. This is especially as China, Japan and India are no longer mythical far-away entities, but economic powers that are yielding native designers who are forging a new identity in Asian-authored fashion. So, what would a modern audience make of Saint Laurent’s Chinese collection if it was shown today?

“I think they would see that he understood the culture,” says Samuel. “Saint Laurent was cultivated and instructed – when you know a culture, you can’t make mistakes. If you only have an aesthetic approach, you can make mistakes.”

Yves Saint Laurent: Dreams of the Orient opens on 2 October 2018 at the Musee Yves Saint Laurent and runs until 27 January 2019.